Return to Theme Table of Contents

Return to VJIC Table of Contents

| Bruce Jackson is SUNY Distinguished Professor and James Agee Professor of American Culture at University at Buffalo. Some of his books are Places: Things heard, things seen (BlazeVox, 2019) Inside the Wire: Photographs from Texas and Arkansas Prisons (Texas, 2013), Being There: Bruce Jackson Photographs 1962-2012 (Burchfield Penney Art Center, 2013), Ways of the Hand: A Photographer’s Memoir 2022. |

Walker Evans: Public photographs 1935-1937

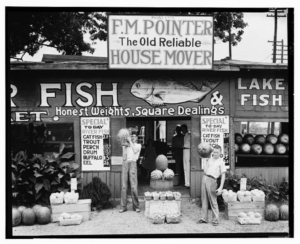

Roadside stand near Birmingham, Alabama

I wrote this to accompany a 1998 exhibit of 100 Walker Evans’s FSA photographs I curated for the University at Buffalo Art Gallery. I thought to update the essay for this series, but there’s nothing in it that needed revising other than the final entry in the Chronology—the 2000 Metropolitan Museum of Art Evans exhibition. When I wrote the essay it was in the planning stage; now it has happened, so I changed that entry to reflect the title of the actual exhibition rather than what was then the pending one. There have been some books and exhibits of Evans’ work since this was written, but none of the exhibits other than the Polaroids have been stuff not seen before. I wrote about them earlier in this series. One important technological change is, high-rez scans some of Evan’s FSA images are now available on the Library of Congress’s “American Memory” website. You can download those files and make passable prints of some of his classic images.

“The Torpor of the Accustomed”

Walker Evans was perhaps the most influential American photographer of the Twentieth century. The work of Robert Frank, Lee Friedlander, David Plowden and Diane Arbus is inconceivable without his photographs and vision. “When I first looked at Walker Evans’s photographs,” Robert Frank said, “I thought of something Malraux wrote: ‘To transform destiny into awareness.’ One is embarrassed to want so much for oneself. But, how else are you going to justify your failure and your effort?”(1)

The influence is not limited to photographers. At the opening of the Museum of Modern Art’s 1971 Walker Evans retrospective, Robert Penn Warren spoke of the first time he had seen Evans’s work: “….Staring at the pictures, I knew that my familiar world was a world I had never known. The veil of familiarity prevented my seeing it. Then, thirty years ago, Walker tore aside that veil; he woke me from the torpor of the accustomed.” (2)

I suspect that we all see much of the time in that “torpor of the accustomed,” and that the work of our best artists both energizes and instructs us so we can see our worlds anew. MoMA curator of photography John Szarkowski wrote in his introduction to the 1971 retrospective, “Evans’s pictures have enlarged our sense of the usable visual tradition and have affected the way that we now see not only other photographs, but billboards, junkyards, postcards, gas stations, colloquial architecture, Main Streets, and the walls of rooms.” (3)

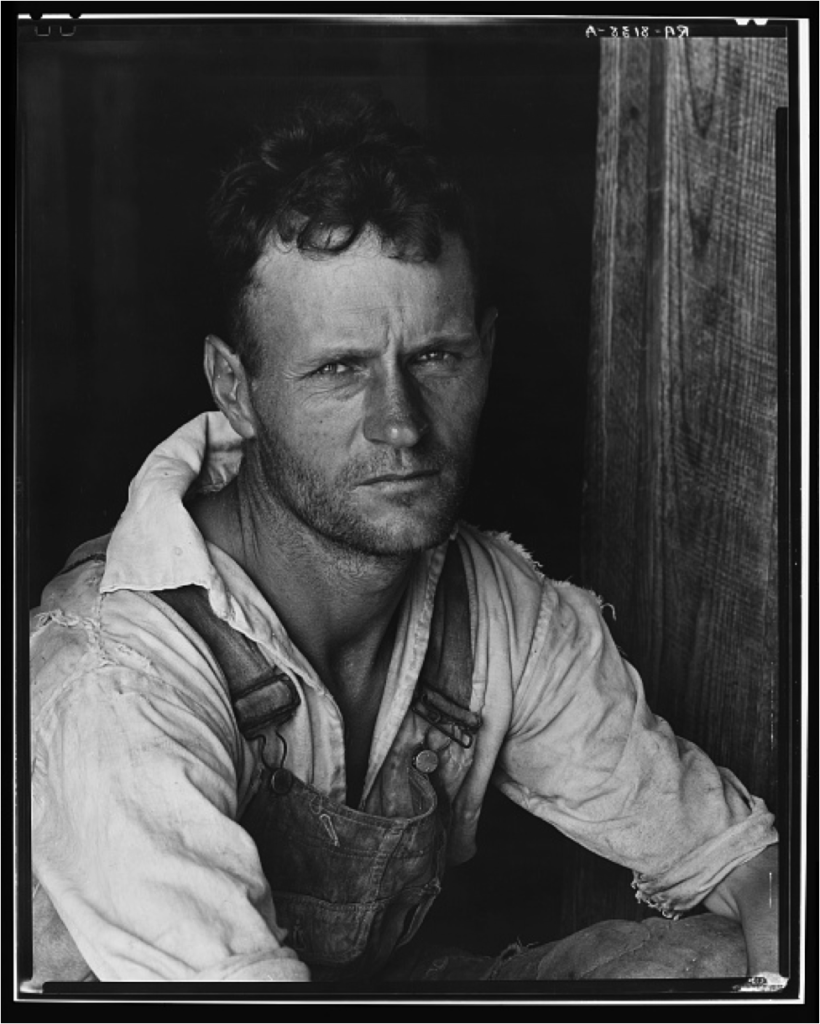

Floyd Burroughs, cotton sharecropper. Hale County, Alabama

“It is difficult to know now with certainty whether Evans recorded the America of his youth, or invented it,” Szarkowski continued. “Beyond doubt, the accepted myth of our recent past is in some measure the creation of this photographer, whose work has persuaded us of the validity of a new set of clues and symbols bearing on the question of who we are. Whether that work and its judgment was fact or artifice, or half of each, it is now part of our history.” (4)

Evans bristled when the word “documentary” was applied to him or his work. “My thought is that the term ‘documentary’ is inexact, vague, and even grammatically weak, as used to describe a style in photography which happens to be my style,” he told a Yale audience in 1964. (5) He told Leslie Katz that “documentary” was “a very sophisticated and misleading word. And not really clear. You have to have a sophisticated ear to receive that word. The item should be documentary style. An example of a literal document would be a police photograph of a murder scene. You see, a document has use, whereas art is really useless. Therefore art is never a document, though it certainly can adopt that style.” (6)

Evans frequently said that the major influences on his thought were Flaubert, Baudelaire and Joyce—writers, not painters or photographers. He spent 1927, the year before he began photographing seriously, in Paris, realizing that he’d have to substitute something else for his early ambition to be a writer. He frequented Sylvia Beach’s Shakespeare & Co. bookshop, where Beach offered to introduce him to Joyce. “But I was scared to death to meet him. I wouldn’t do it. He came in, and I left the shop. He was my god. That, too, prevented me from writing. I wanted to write like that or not at all.” (7)

“…I know now that Flaubert’s esthetic is absolutely mine,” he told Leslie Katz. “Flaubert’s method I think I incorporated almost unconsciously, but anyway used in two ways: his realism and naturalism both, and his objectivity of treatment; the non-appearance of author, the non-subjectivity. That is literally applicable to the way I want to use a camera and do. But spiritually, however, it is Baudelaire who is the influence on me…. I consider him the father of modern literature, the whole modern movement, such as it is. Baudelaire influenced me and everybody else too.” (8)

“A Few Nice ‘Sirupy’ Pictures”

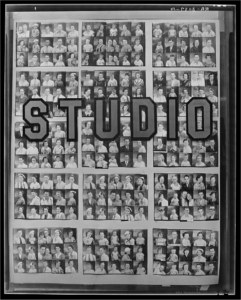

Photographer’s window of penny portraits. Birmingham, Alabama

Walker Evans’s career as a photographer was almost five decades long, beginning shortly after his return from his Wanderjahr in France in 1928 and continuing to the year before his death in 1975. But he is best known for the images he created in the fifteen-month period between June 1935 and August 1936 when he was employed by the Resettlement Administration (later named the Farm Security Administration (FSA).

The first solo show of photographs at the Museum of Modern Art was Evans’s “American Photographs” in 1938; 63 of the photographs in that show were from Evans’s RA/FSA period. (9) All the photographs in both editions of Let Us Now Praise Famous Men were made during that period, as were 44 of the 100 images in the book of the 1971 MoMA retrospective, and 21 of the 44 images in Aperture’s Walker Evans (1993). Photographs from the RA period appeared on the covers of all those books, as well as the cover of the massive Getty catalog published in 1995.

The RA hired Evans for three months beginning in June 1935. In September of that year, he and Ben Shahn were the first full-time photographers appointed by Roy Stryker, the new director of the RA’s Historical Section. Evans did field photography for the RA in West Virginia, Pennsylvania, Louisiana, Mississippi, Georgia, South Carolina and Alabama. In February 1937, he and Edwin Locke photographed flood victims in Arkansas and Tennessee. (10) His photographs are the best known of those produced by any of the full-time RA (later Farm Security Administration) photographers even though he made fewer photographs than any of them.

The RA project was designed to create propaganda for the Roosevelt administration’s New Deal. It is difficult to imagine someone less suited for propaganda work than Walker Evans. His papers include a handwritten draft memorandum regarding the RA job that seems to have been written in spring 1935, before he ever did any assignments for the government:

Never under any circumstances asked to do anything more than

these things. Mean never make photographic statements for the

government or do photographic chores for gov or anyone in gov,

no matter how powerful-this is pure record not propaganda. The

value and, if you like, even the propaganda value for the government

lies in the record itself which in the long run will prove an intelligent

and farsighted thing to have done. NO POLITICS whatever (11)

He was right. The propaganda of the thirties grows ever more tedious and vapid; watch, if you can bear it, The Plow that Broke the Plains, or try reading aloud Tom Joad’s last speech in The Grapes of Wrath. Evans’s photographs are as vital and lucid as they ever were.

Even though it was Evans’s vision that most informed Stryker’s sense of the project in its early years, the two existed in what was at best a state of uneasy truce. Stryker was sentimental; Evans was clinical. Stryker was a populist and activist; he wanted specific assignments completed on time, activity reports, pictures that could be used in magazines and books to promote the New Deal’s image and goals. Evans was elegant and apolitical; he liked to be out there on his own, sending in pictures now and then. (Jeff Rosenheim, of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Department of Photographs, thinks it likely that Evans sometimes sent Stryker negatives he’d made a year or two earlier, just to shut him up and keep the paychecks coming.) For Evans, photography was about art; for Stryker, “the photograph is only the subsidiary, the little brother, of the word.” (12) Stryker was capable of sending Evans letters with lines like: “Try to get us a few nice ‘sirupy’ pictures of agricultural scenes and general landscape pictures for cover pages.” (13) No one who knew the two men was surprised that when the budget tightened in March 1937 Evans was the first person Stryker fired.

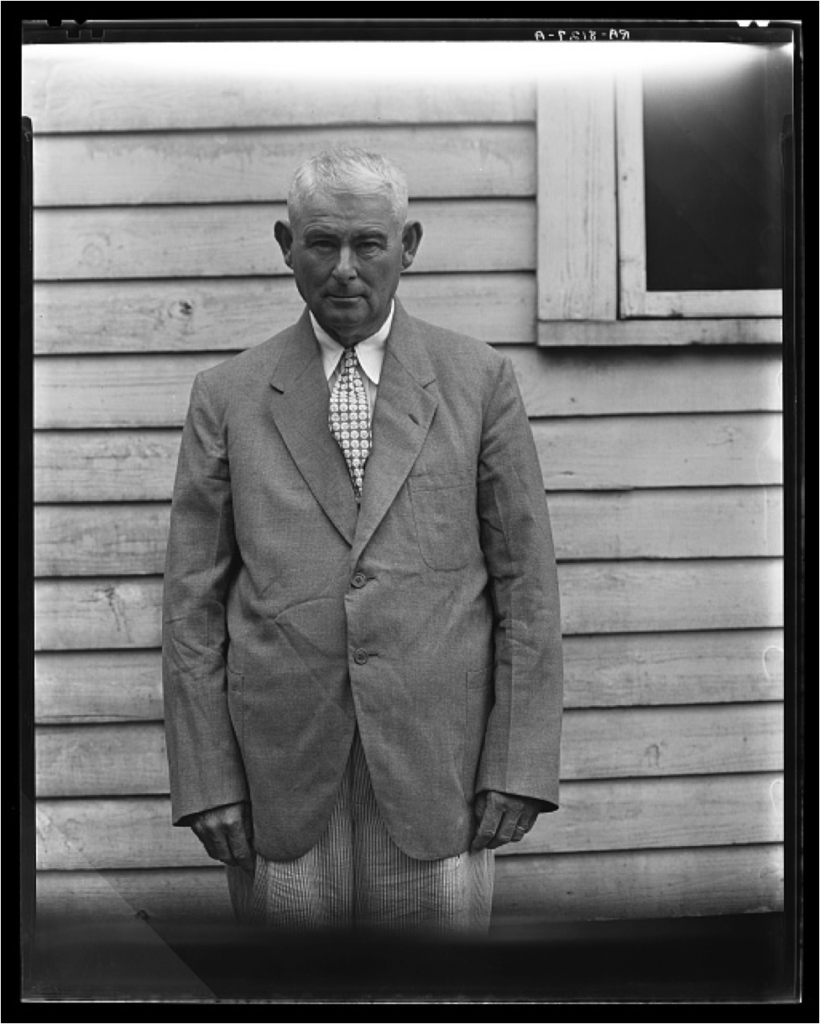

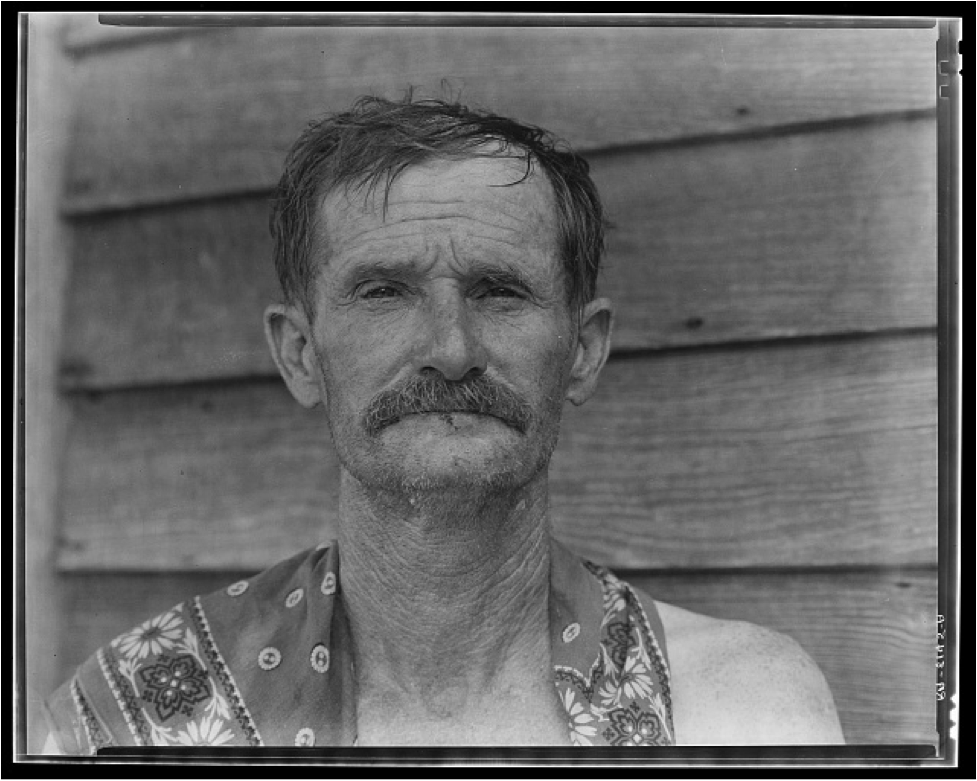

Landowner in Moundville, Alabama

By that time, Evans had become engaged in the project that would have more significance than anything he had done thus far in his career. In the spring of 1936, James Agee had been assigned by Fortune to do a magazine piece on tenant farmers. He said he wanted Walker Evans to be his photographer. The publishers asked Stryker to release Evans for a few months. Stryker was probably happy to have Evans off his hands but he imposed one condition: Evans could go to Alabama with Agee and Fortune could publish the pictures, but the negatives would be the property of the American people. (14)

Agee’s manuscript was too long and too angry for a magazine devoted to the glory of American business. Fortune turned it down. Agee kept writing, rewriting, expanding, and in the spring of 1941, maybe the worst of all possible times, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men was published. The Depression was over, the nation was tooling up for war, no one was interested in a verbal and visual poetic exploration of the condition of tenant farmers in the American southeast. The small first edition was eventually remaindered. Then something remarkable happened. When the book was reprinted in 1960, it was hailed as an American classic, one of those key works that, like Leaves of Grass and Moby Dick and The Sound and the Fury, you had to know if you were going to know what America was all about. Roy Stryker’s bad boy had entered the canon.

III. “It’s Not the Camera”

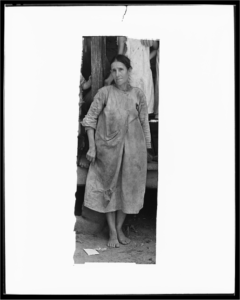

Mrs. Frank Tengle, wife of a cotton sharecropper. Hale County, Alabama

Throughout his career, Evans continually tuned his work. He was always aware of position and juxtaposition, and in shows and publications he fought to control both. When he worked for Fortune, he sometimes cut his negatives with scissors to be sure the layout editors included no more of the image than he wished. The 1938 MoMA exhibit and book differ in major ways: Evans substituted some prints for others and cropped some that were common to both differently. The 1960 edition of Let Us Now Praise Famous Men has twice as many photographs as the 1941 edition—62 compared to 31—and many of the photographs common to both volumes are cropped differently. “I’ll do anything to get one photograph,” Evans said. “Stieglitz wouldn’t cut a quarter of an inch off a frame. I would cut any number of inches off my frames in order to get a better picture.” (15) For Evans, negatives were fields of possibility, not absolute conditions.

Crossroads store. Sprott, Alabama

“People keep asking me what kind of camera I use,” Evans said to me in March 1974. “I tell them it’s not the camera. It’s this.” With his right index finger he touched his right temple. It is indeed the mind of the maker that determines the photograph, but different kinds of cameras see things differently. The 35mm Leica is used at eyelevel, the 2.25 x 2.25 Rolleiflex at breastbone or waist level, so the instruments provide different sightlines and proportions and feelings. With the 35mm, you can snap off pictures quickly, as Evans did of the Tengle family in Hale County when they seemed to be getting ready for a more formal 8×10 portrait. And you can even spy with it: Evans sometimes used an attachment that let him point his Leica in one direction but actually take pictures to his right or left. He was sneakier on a grander scale in the series of pictures he made in 1938 and 1942 in New York subways: he fitted a 35mm Contax under his jacket and ran the shutter release cable through his sleeve. You can’t be sneaky with an 8×10. It’s an enormous box with the lens mounted on a board in front that is connected to the box by black bellows that snake further or closer to focus; parts of the camera tilt to straighten the camera’s tendency to hasten the vanishing point of parallel lines. The photographer must duck under a dark cloth where he looks at an image that is upside down and backwards. After composing and focusing, he slides the film holder into place, takes out the protective slide, cocks the shutter, and takes a single picture. He then inserts the slide and locks it into position. If he wants to take another picture, he takes out the film holder and repeats the entire process. The 8×10 by its very nature is a meditative instrument. The extraordinary depth of field, range of detail and sharpness of image in Evans’s 8×10 contact prints are well-earned.

Near the end of his life Evans discovered and fell in love with the Polaroid SX-70. His student and friend Jerry L. Thompson wrote: “He carried this camera with him on his daily outings, making hundreds of pictures of signs, bits of litter, and the faces of his friends and students.” (16) The artist William Christenberry told me that on the trip to Hale County the two of them took in 1973, Evans had with him a Rolleiflex twin lens reflex and the Polaroid SX-70, but Evans never once uncased the Rolleiflex. At the opening reception of a 1974 University of Texas exhibit of the 1936 Hale County photos, Evans walked up to a wall of prints, took his SX-70 from a leather holster on his hip and began recapturing the images he had made thirty-eight years earlier.

A few years before he discovered the SX-70 Evans told Paul Cummings that he had a “psychological block” about taking pictures of friends. “I haven’t analyzed it very much. I was around Hemingway a little bit, but I would never bring out a camera and photograph him, out of regard for him really, as too obvious a thing to do. I thought too much of our relationship to throw a camera into it.” (17) The SX-70 seems to have dissolved the psychological block. So far as I know, the Polaroid years were the only time Evans went around freely snapping photographs of friends and students. He made thousands of them, far more than he made for the RA. (18)

In earlier years Evans often professed disdain for color photography (though he had published many beautiful color images in Fortune), but with the Polaroid he did some of his most beautiful found-object work in color. The SX-70 freed Evans to work quickly; it was the polar opposite of the 8×10 view camera. He said of it, “A practical photographer has an entirely new extension in that camera. You photograph things that you wouldn’t think of photographing before. I don’t even yet know why, but I find that I’m quite rejuvenated by it. With that little camera your work is done the instant you push that button. But you must think what goes into that. You have to have a lot of experience and training and discipline behind you. . . . It’s the first time, I think, that you can put a machine in an artist’s hands and have him then rely entirely on his vision and his taste and his mind.” (19)

An Archaeologist of the Present

History is always afterwards, a narration possible only after something is over. Evans’s vision puts before us a perpetual present. What changes are our associations, the reverberations the images and their juxtapositions occasion in us.

Photographs are specific and self-contained; whatever referentiality exists is coincidental. A photograph may be contextualized by its relation to other photographs (as, say, in series on a gallery wall or with the photographs that precede and follow in a book), and it may be contextualized by its relation to the quotidian, which always requires external information. That external information may be very close, as, for example, James Agee’s text which immediately follows Evans’s photographs in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. It may be our own, in which case it is always partial, transient, relative: the external information I bring to a photograph of Lyndon Johnson is not what my children bring to a photograph of Lyndon Johnson or what you bring to a photograph of Lyndon Johnson, and the information you or I bring to that photograph today is not what we would have brought to it a decade ago or twenty years ago.

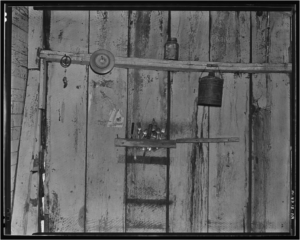

Kitchen wall in Bud Fields’ house. Hale County, Alabama

If Evans’s photographs are taken as a historical record, they are of course insufficient. But mere historical record was never his intention. The photographs are, however, items upon which or with which a history might be constructed, just as bits of pottery and fragments of bone are items upon which a history might be constructed. At one level, Evans is an archaeologist of the present. “The objective picture of America in the 1930s made by Evans,” he wrote in an unpublished introductory note for the 1961 reissue of American Photographs, “was neither journalistic nor political in technique and intention. It was reflective rather than tendentious and, in a certain way, disinterested. . . . Evans was, and is, interested in what any present time will look like as the past.” (20)

There is a tension of meaning in every one of these images. The same visual object that forever seizes a present moment is always an image of the past, even the Polaroids that blossom into full color sixty seconds after the event. How could it be otherwise? Just as the present becomes the past as soon as we can be aware of it as having happened, photographic images are the past as soon as we close the shutter. All photographs made in the camera are grounded in temporality. They all are of something; none is sui generis.

Evans frequently used the words “anonymous” and “anonymity” when talking about his photographs. He didn’t take pictures of famous people, he didn’t take pictures of dramatic events, and—with few unavoidable exceptions—he didn’t intrude into his images. He was immaculately conscious of and attentive to everything he did. The result is an astonishing body of art that seems to be the most unselfconscious of all.

Bud Fields, cotton sharecropper. Hale County, Alabama

Notes

- Robert Frank, “A Statement,” U.S. Camera Annual, 1958, p. 115. Not all American photographers were so enamored of Evans’s work. The nature photographer Ansel Adams wrote in a letter to Edward Guston: “Walker Evans’s [American Photographs] gave me a hernia. I’m so goddamn mad over what people from the left tier think America is,” Belinda Rathbone, Walker Evans: A Biography (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1995), p. 166.

- Rathbone, p. 284.

- John Szarkowski, Walker Evans (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1971), p. 17.

- Szarkowski, p. 20.

- Jerry L. Thompson and John T. Hill, eds. Walker Evans at Work (New York: Harper and Row, 1982), p. 238. (hereafter WEAW)

- Leslie Katz, “Interview with Walker Evans,” Art in America 59 (March-April 1971), p. 87.

- Paul Cummings, Artists in Their Own Words (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1979), p. 85.

- Katz, p. 84.

- Actually, there was another show at MoMA comprised entirely of Evans’s photographs before the 1938 show: “Photographs of Nineteenth-Century Houses” in 1933. But Evans considered that a show of something for which he simply provided the images: “The one in 1938 was more important. That’s the one I remember, because to my mind it was the first big photography show that I’d had, and it was the first big one that the museum gave. I don’t consider that business about architecture in 1933 a show” (Cummings, pp.93-94). Historians of photography have accepted the distinction, e.g. Alan Trachtenberg, Reading American Photographs: Images as History, Mathew Brady to Walker Evans (New York: Hill and Wang, 1989), p. 238: “The 1938 exhibition, the first one-man show by a photographer at the Museum of Modern Art….”

- There are about fifty 35mm negatives from what seems to have been a one-day shoot in New York City in the summer of 1938, but it is not clear which, if any, of those negatives were shot by Evans. Some historians think most and perhaps all of them were actually made by Evans’s close friend, Ben Shahn.

- WEAW, p. 112.

- Roy Emerson Stryker and Nancy Wood, In This Proud Land: America 1935-1943 as seen in the FSA Photographs (New York Graphic Society: Greenwich, CT, 1973), p. 8.

- The letter is undated but is probably from December 1936 or January 1937. WEAW, p. 118-119.

- As were all the other negatives made by Evans while he was in the pay of the RA, and all the negatives made by Dorothea Lange, Arthur Rothstein, Gordon Parks, and the other photographers who worked on the project.The whole project was and remains one of the best art bargains ever made on behalf of the American people: all these negatives are in the public domain. The Library of Congress will make prints of any of them for a small processing fee. For order forms, prices and other information, contact the Photoduplication Service, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540-5230.

- Katz, p. 86.

- WEAW, p. 17. See also Thompson’s excellent memoir, The Last Years of Walker Evans: A Firsthand Account (New York: Thames and Hudson, 1997).

- Cummings, p. 97.

- No one knows how many photos Evans made while he worked for the RA or even how many Stryker kept. Stryker had a practice of “killing” photographs that didn’t appeal to him. Killed sheet film was given to the photographers or thrown out. The 35mm film was cut into strips of 5, so often images Stryker liked and disliked were on the same strip. For a while he solved that problem by punching holes in the negatives he didn’t think ought to be printed. The usual estimate is about 1000 Evans images in the Library of Congress RA/FSA collection, but Jeff L. Rosenheim, who oversees the Evans Collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, thinks the number may be closer to 1500.

19.WEAW, p. 235.

20.WEAW, p. 151.

Chronology, Selected Solo Exhibits, and Major Publications

1903 Born November 3 in St. Louis, Missouri.

1922-23 Graduates Phillips Andover, attends Williams College.

1926-27 Travels in Europe.

1929 MoMA opens in temporary quarters.

1930 First 3 photographs published in first edition of Hart Crane’s The Bridge.

1933 May and June: makes photos in Cuba for Carlton Beals’s The Crime of Cuba, and hangs out with Hemingway. “Walker Evans: Photographs of Nineteenth-Century Houses” at MoMA. (The show travels to several locations, including Buffalo’s Albright Art Gallery.)

1935 “African Negro Art: A Corpus of Photographs by Walker Evans” at MoMA. Hired by RA June 24, works for Resettlement Administration in June and July and then appointed to “permanent” position September 16.

1936 Summer in Hale County, Alabama, with James Agee. In the fall, Evans works on a film project with Ben Shahn (it is never finished).

1937 Fired by Stryker March 23.

1938 “Walker Evans: American Photographs” at MoMA’s temporary under-ground gallery in Rockefeller Center (the show travels to 10 venues, including Buffalo’s Garret Club). American Photographs published. Begins taking secret photos in New York subways that he won’t complete until 1942 and won’t show until 1966.

1941 Guggenheim fellowship.

1941 Let Us Now Praise Famous Men published.

1943-45 Staff reviewer for Time.

1945 Becomes staff photographer at Fortune, later Photographic Editor and then Associate Editor. He continues photographing and writing until 1965. Fortune publishes 42 of his portfolios, some with color images, many with text by Evans.

1948 “Walker Evans Retrospective,” Art Institute of Chicago.

1955 James Agee dies.

1959 Second Guggenheim fellowship.

1960 Second edition of Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.

1962 “Walker Evans: American Photographs,” MoMA. Photographs from the 1938 exhibition.

1964 “Walker Evans,” The Art Institute of Chicago.

1965 Appointed professor of Photography/Graphic Design at Yale.

1966 Publication of Many Are Called and Message from the Interior. “Walker Evans: Subway Photographs” at MoMA.

1971 “Walker Evans,” MoMA, publication of Walker Evans.

1973 Elected to National Institute of Arts and Letters.

1974 Becomes professor emeritus at Yale. “Photographs from the ‘Let Us Now Praise Famous Men’ Project,” University of Texas.

1975 Dies April 10 in New Haven.

1978 “Walker Evans” Sidney Janis Gallery, New York. Publication of Walker Evans: First and Last.

1982 Publication of Walker Evans at Work, edited by John T. Hill and with an essay by Jerry L. Thompson.

1983 “Walker Evans 1903/1974,” IVAM Centre, Valencia, Spain.

1989 “Havana 1933,” Paris, FNAC, publication of Walker Evans: Havana, 1933.

1990 “Walker Evans Amerika: Bilder aus den Jahren der Depression.” Städische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich.

1993 “Walker Evans: Polaroids 1973-1974.” 292 Gallery, New York.

Publication of Walker Evans: The Hungry Eye, edited by John T. Hill and with text by Gilles Mora.

1998 “Walker Evans: Public Photographs 1935-1937”. University at Buffalo Art Gallery, Research Center in Art+Culture.

1998 “Walker Evans: Simple Secrets.” High Museum of Art. Atlanta.

2000 “Walker Evans,” Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accompanied by a collection of letters, essays and unpublished notes, edited by Jeff L. Rosenheim.

Acknowledgments

I’d like to thank the following for their help in arranging the exhibition and preparing these comments: Diane Christian, William Christenberry, David Coleman, Bill Ferris, Carl Fleischhauer, Loren Goodman, Reine Hauser, Barbara Natanson, Dean Ortega, Stephanie Ortega, Jerry L. Thompson, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center (University of Texas), The John Paul Getty Museum, and the Library of Congress. I particularly want to thank Jeff L. Rosenheim, Assistant Curator, Department of Photography, Metropolitan Museum of Art. Jeff gave me access to resources of the Walker Evans estate, vetted and corrected the captions for the images in the exhibition, answered scores of questions, and consistently provided invaluable advice grounded in his years of working with Evans’s legacy.