Return to Theme Table of Contents

Return to VJIC Table of Contents

Theme editor:

Bruce Jackson is SUNY Distinguished Professor and James Agee Professor of American Culture at University at Buffalo. Some of his books are Places: Things heard, things seen (BlazeVox, 2019) Inside the Wire: Photographs from Texas and Arkansas Prisons (Texas, 2013), Being There: Bruce Jackson Photographs 1962-2012 (Burchfield Penney Art Center, 2013) and Ways of the Hand: A Photographer’s Memoir (SUNY Press 2022)

Walker Evans Polaroids

I

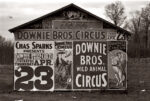

Walker Evens. FSA

I had a chance encounter with the photographer Walker Evans in Austin, Texas, in 1974. Evans was there for the opening of an exhibit of his 1930s Farm Security Administration photographs at the University of Texas Harry Ransom Center; I was there delivering mounted prints of photographs I had done over the past few years at Cummins prison farm in Arkansas for an exhibit at the University’s Texas Union.

Evans was staying with his former Yale student, William Stott (author of Documentary Expression and Thirties America, New York: Oxford University Press, 1973), who had organized the exhibit. My wife Diane Christian and I were staying with two University of Texas friends: folklorist Roger Abrahams and anthropologist Barbara Babcock. Roger told us about the Evans exhibit, which was to open that night, and said, “Would you like to meet him?” I could barely restrain my delight. Evans was, and remains, one of my photographic masters. When I was in my early teens, I visited New York’s Museum of Modern Art almost every week; the documentary photograph room was one of my regular stops. The book Evans did with James Agee, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1940), would be among the top two entries of my list of greatest American prose works of the 20th Century (the other is William Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom!, 1936).

Evans was staying with his former Yale student, William Stott (author of Documentary Expression and Thirties America, New York: Oxford University Press, 1973), who had organized the exhibit. My wife Diane Christian and I were staying with two University of Texas friends: folklorist Roger Abrahams and anthropologist Barbara Babcock. Roger told us about the Evans exhibit, which was to open that night, and said, “Would you like to meet him?” I could barely restrain my delight. Evans was, and remains, one of my photographic masters. When I was in my early teens, I visited New York’s Museum of Modern Art almost every week; the documentary photograph room was one of my regular stops. The book Evans did with James Agee, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1940), would be among the top two entries of my list of greatest American prose works of the 20th Century (the other is William Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom!, 1936).

Walker Evens FSA

Roger called Bill Stott, and shortly thereafter, Diane, our twelve-year-old son Michael, Roger, and Roger’s son Rod, were at Bill’s house.

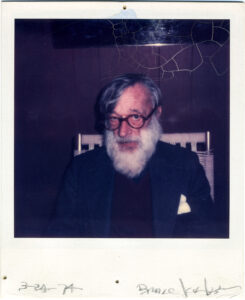

Polaroid of Walker Evans taken with his SX-70

Walker was then particularly excited about his Polaroid SX-70, which he’d gotten a year earlier. The Polaroid Corporation, in an attempt to make the camera respectable, had picked a small number of artists and given them cameras and all the film packs they could use (some of the others were Ansel Adams, Andy Warhol, and Helmut Newton). He had his SX-70 in a belt holster. He took it out and showed it to me. He took pictures of Diane, Michael and me, some of which he kept, some of which he gave us.

(Polaroid’s gift wasn’t the only reason or even the prime reason he was using the SX70. Bill Stott wrote me recently that, “Walker told me that he didn’t have the energy to take photos with the cameras he’d used earlier. I had the impression he was working only with the camera Polaroid gave him.” Great artists adapt to the to their own capabilities and the tools at hand: think late Monet, Matisse and Chuck Close.)

“Try it,” he said. I took pictures of him. Two Polaroids from that day are in my kitchen now: one he took of Michael and one I took of him.

In that conversation, he said something I’ve often quoted since: “People ask me what camera I used. It’s not the camera. Its—.” He tapped his temple with his index finger: it’s the eye and the brain.

“People ask me what camera I used. It’s not

the camera. Its—.” He tapped his temple with

his index finger: it’s the eye and the brain.

Well, yes and no. Different cameras and lenses “see” differently. It was always Walker Evans taking Walker Evans photos, but the photos he took with his 8×10” and smaller view cameras, his Rolleflexes, his Leica, and his SX-70 differed from one another. It was his brain and eye determining the camera settings and when the shutter was fired, but those various cameras performed and functioned as differently as a flat and a Phillips head screwdriver. Cameras were the tools of his craft; he decided which tool he would use for which purpose; each of them had its own visual voice.

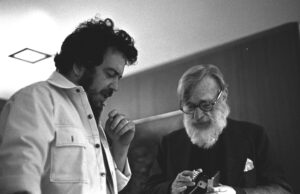

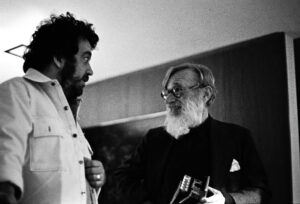

Photo © Diane Christian, Bruce Jackson and Walker Evans

Evans asked why I was in Austin and I told him about the Texas Union exhibit. He asked if he could see the prints before I dropped them off. We made a date to meet the next afternoon. Our group went back to Roger’s and Barbara’s house. A few hours later, Diane, Roger, Barbara and I went back to Stott’s house to join them for the drive to the Harry Ransom Center for the opening of the exhibit.

Evans was delighted with the mounted and framed FSA photos. He apparently hadn’t seen them in some time. “But why does this place have these prints and I don’t?” he asked Bill Stott.

“Because you sold them,” Bill said. Evans harrumphed. A few minutes later, I saw him taking Polaroid photos of the installation.

I didn’t have a camera with me. It had been a conscious choice: I wasn’t going to go to a photo exhibition opening with Walker Evans being the guy taking pictures. But Bill Stott had a Nikon hanging around his neck. I rushed over to where he was talking to someone and said something like, “Bill: come over here. It will be the metaphotograph of metaphotographs: Walker is taking Polaroids of his own FSA prints!”

Stott looked at me with annoyance. “In a minute, in a minute. I’m talking to someone.” By the time he’d finished talking to that someone, Evans had reholstered his SX-70. The moment was gone. (Not having my own camera with me has been an error I have not repeated since. And now, in the smartphone era, nearly everyone has a camera at hand all the time.)

Photo © Diane Christian, Bruce Jackson and Walker Evans

The following day, Diane and I went back to Stott’s house. Evans went through my photos one by one, saying nothing. I can remember no exam at which I was so nervous. There was one he said he had to have. I said I’d send him a print. He said that photographers always promise to send prints but never did. I said this one was part of the exhibit. He said that if I gave him this one, he’d send me one in exchange. How could I say no? I gave him the mounted print.

No print ever came. We exchanged a few letters, but no print. William Ferris, who had known Evans at Yale, later told me Evans did that all the time. He died with a lot of other people’s prints in his house.

In 1998, twenty-four years later, I was doing some research in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection of Walker Evans materials. I was then curating a University at Buffalo exhibit of Evan’s FSA work. One of the Met’s photo curators, Jeff Rosenheim, came to the table where I was working. He was holding a large matted print.

“There’s maybe something you can help us with. This was in Walker’s collection. It’s different from anything he did. We can’t figure out the provenance.”

“It’s a picture I gave him,” I said. I told him the Austin story.

II

Cover: Walker Evans Polaroid Book

Four years later, Jeff’s book, Walker Evans: Polaroids (Scalo Zurich, in association with the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2002), was published. It is the only published collection thus far of the final phase of Evans’s long and influential career.

I think it misses the point of those pictures in two important regards, one having to do with the character or voice of Polaroids, the other with their place in Evans’s body of work.

Many of his Polaroids are like his old photos, but with two differences: they’re in color and they lack visual nuance. He did color for some of his Fortune assignments, but, until the SX-70, he never much liked it. SX-70 images simply do not have the dynamic range of negative film: the dark areas on buildings in his earlier photos had a long scale going from bright to dark; these have the tonal range of mud.

Google search October 2022

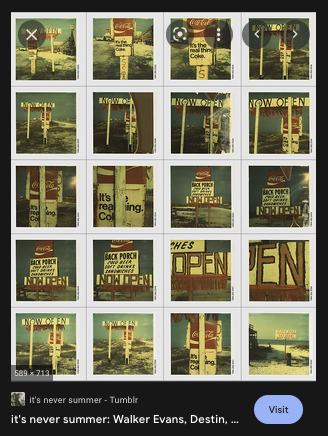

Jeff wrote in his introduction that there were more than three thousand Evans Polaroids. For his book, he opted for the graphic pictures—road lane paint, signs—and buildings. Evans always loved signs and artifacts. The walls of his home were covered with signs he stole from highways and barns. In 1931, Evans made a photograph of a large picture of the window of a wood house; inside the window was a large photo of Herbert Hoover. One of the Polaroids is very much like it: a decaying house with, inside the window, an upside down sign with a large painted hand and the word “Palmist” (He took that photo on a 1973 visit with artist William Christenberry to Hale County, Alabama, where he and Agee had done their work for Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. Christenberry subsequently got the sign and put it on his own wall. “I sent Walker a photo of it there,” Bill told me. “I knew he’d have a fit.”)

Google search, October 2022

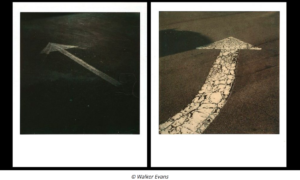

Rosenheim’s book has 121 images. Nineteen of them are road lane markers: white dashes and arrows painted on pavement. There are twenty-two buildings, none with any detail in the shadow areas. Evans’s prints made from negative film prints are full of shadow area detail.

What’s to conclude: that Evans had a new aesthetic, one that tossed aside the tonal precision for which he was so well known, and that he’d spent a lifetime perfecting, or that he had made a tradeoff, as had everyone else, to Polaroid’s limited tonal range?

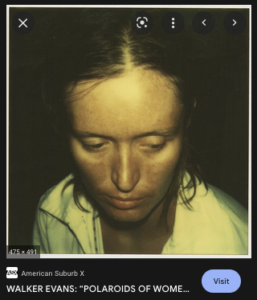

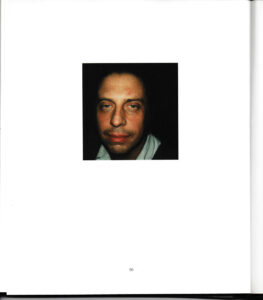

Walker Evans Polaroid

What was entirely new in Evans’s Polaroids are the color portraits of people he was hanging out with. In his entire career, he’d done remarkably few hanging-out photos. In 1929 and 1930, he took photos of Ben Shahn, Hart Crane and Lincoln Kirsten; the images are almost all very formal, very posed. There are hardly any photos by him of family, cronies, lovers, children, drinking-pals. He famously spent two weeks drinking with Ernest Hemingway after finishing his shooting assignment in Cuba for Carlton Beals’s The Crime of Cuba (1933); he took not a single photograph during that encounter.

He was no more likely to take hanging out snapshots than a surgeon to slice his steak with a scalpel. In his professional photographer days, the camera was an instrument, one to be used precisely and specifically. With film, Evans stalked the light; with the SX-70, he just snapped away. Had our 1974 Austin encounter occurred twenty years earlier, there would be Diane’s and my 35mm photos of him; there would have been none by him of us.

Walker Evens Polaroids, Web image: https://www.anatomyfilms.com/walker-evans-polaroids/

Rosenheim’s book includes only five casual portraits, the kind of photograph the camera was designed to make. I suspect that Rosenheim, in editing that book, saw the Polaroids in terms of Evans’s past rather than his present. With the Polaroid, Evans made images of the things he’d made images of for decades; that’s what he knew how to do. But what excited him were people in the room. I saw that happen. He may have made more photos of objects than people with the SX-70, but it was the people photos that lit him up and that were new. You can find many of them on the Web.

Walker Evans Polaroids online:

https://www.anatomyfilms.com/walker-evans-polaroids/

https://americansuburbx.com/2011/09/walker-evans-polaroids.html

Yale University Art Gallery: 2,133 images:

https://artgallery.yale.edu/overall-search/walker%20evans%20polaroids

https://artgallery.yale.edu/overall-search/walker%20evans%20polaroid

All of that goes to the matter of image selection in Walker Evans: Polaroids. More serious is the mutilation of every image in the book but one.

Google search Polaroid SX 70 October 2022

The Polaroid image is a 3.135” square. It comes out of the camera embedded in a 3.483” x 4.233” paper frame. In exchange for camera and film speed (the maximum shutter speed was 1/175; the film had an exposure index of 180: you couldn’t shoot things in motion with it; it wasn’t made for that) and tonal range, the Polaroid put a real picture in your hand in sixty seconds.

Polaroid photos aren’t just documents of a moment, as are almost all other photographs. They are also things, specific objects, with a trajectory in time. Some hold up well. Some show their age with cracks, discolorations, a stain or a color shift toward green. They enter the world embedded in that paper frame. That frame is not ancillary to the picture; it is part of it. That frame tells us what kind of picture we’re looking at. If you’ve seen Polaroid pictures, you know immediately that they don’t look like pictures made from negatives or transparencies, so you don’t read or judge them by the same standards.

Image from Walker Evans polariods

There’s something else, something equally important, that sets them apart: most people responded very differently to someone taking a photo with an SX-70 than someone taking a photo with a view camera on a tripod, or a Rolliflex or a Leica. It was very much like the difference now between taking a photo with a smartphone and taking one with a Nikon or Canon or Sony. Most people pay little or no attention to someone making smartphone pictures; the cameras are ubiquitous, so people relax. It shows in the images. I think that’s what Walker Evans was delighting about with his SX-70.

Everyone, back then, knew what a Polaroid was all about, and acted or reacted accordingly. And knew, when they saw that paper frame, how to read the picture they were looking at.

But every image in Walker Evans: Polaroids—except the one on the cover—has that paper frame cut off. Each page has what appears to be a very small, very murky, picture of something or someone. You can remind yourself again and again that what you’re looking at is a reproduction of a Polaroid, but that’s not what you’re seeing.

Page from Walker Evans Polaroid book

By cutting off the frame in which the square picture is embedded, the visible evidence of what kind of photo is being seen is abolished. If the frame is there, a looker understands why the scale from light to dark is far less subtle than with film. If it is there, a looker assumes that the image hasn’t been cropped. If it is there, the viewer is reminded that each image is a specific physical object, one that exists in time. Those artifacts of the medium are no more disturbing than minor grammatical errors in the English of someone with a heavy foreign accent.

The Polaroids were one of the few times in his career that Walker Evans didn’t have someone else between him and his prints: no John Hill, no Jerry Thompson. Not only were the people who printed for him absent, but so was the delay between firing the shutter and having the print in hand. The camera and the Polaroid process did it in a purely mechanical, uncaring, neutral way. He loved that. The subtraction of the frames, the visual context, in Walker Evans: Polaroids tosses that away.