Return to Theme Table of Contents

Return to VJIC Table of Contents

Bruce Jackson

Intermezzo: Notes on words and process

Some of the responses to the articles in this series have come from working photographers. Some of them have experience in film and the darkroom; some have worked only in digital. Other responses have come from readers interested in photography, or in the subjects I’ve discussed thus far, but have limited or no experience doing it.

I want to take a break in this series looking at the work of other people to clarify my use of certain terms and say a few things about my sense of the photographic process. For experienced photographers, most or all of this will be obvious. For those unfamiliar with these matters, these notes may help ground what I’m saying in this series about the work of others.

Nothing of what I say in “Intermezzo” goes to the use of various kinds of photographic work or play. The notes apply equally well to an Avedon portrait, a prom snapshot, documentation of solar flare, an image on a driver’s license or in a passport, an image on a gallery wall or the page of a newspaper or stored on a smartphone.

The word “photography”

The word “photography” is too vague, too broad, to be of much use on its own. That is the basic failure of Sontag’s On Photography: she ignores the distinctions and clarifications that let us know what we’re talking about, that let us know what matters and what doesn’t. “The referent adheres,” Roland Barthes writes in Camera Lucida. Sontag ignores that critical fact. Barthes will, as I’ll discuss in the next essay in this series, struggle with it, and try to transcend it.

Words like “photography,” “painting” and “writing” need modification if we are to make anything of what we are talking about, hearing, reading or seeing.

If our subject was painting, we would need to know if we were considering paint applied to a canvas, lanes on a highway, a house. If our subject was poetry, we would have to know if were parsing a Shakespearean sonnet, a Hallmark birthday card, a rap performance, a verse on a the wall of a barroom WC. Poetry may be written or it may be oral; it may be fixed (“Tintern Abbey”) or it may be situational (the fluid lyrics of a convict worksong). If written, the words may be designed for the mind’s ear (a book), or as the basis of performance (the script of a play, the text of a speech).

Likewise with “photography.” The word “photography”

has to do with images written in light. That’s it.

A “photograph” is a manifestation of an image

written in light. It may be unitary—written

on a surface that becomes the usable image

or it maybe intermediary in the

creation of a usable image.

Likewise with “photography.” The word “photography” has to do with images written in light. That’s it. A “photograph” is a manifestation of an image written in light. It may be unitary—written on a surface that becomes the usable image or it may be intermediary in the creation of a usable image.

The unitary photograph (Daguerreotype, tintype, Polaroid, e.g.) is what is left in the same place after the original recording is processed. The exposed silver-coated Daguerreotype surface, for example, is fumed in mercury vapor, cleansed of chemicals, and washed. The exposed Polaroid sheet passes through compression rollers that release chemicals that render a fixed image. (Unless someone manipulates the just developed surface before the chemical process is complete, as photographer Les Krims did in 1960s. In that case, Krims’ rubbing the developing surface during the first 60 seconds out of the camera, when the developing process was still going on and the image was still unstable, was just one more step in the developing process.)

Negative film serves as an intermediate agent for the production of a positive print: with few exceptions (X-rays, e.g.), it is not used for anything else.

The information received by a digital camera’s sensor is translated to a digital file, which then, not unlike the photographic negative, serves as the intermediate for a positive image on a computer screen or a physical print.

Reversal film (Kodachrome, etc.) straddles the two. If the film is small (35mm), it needs a projection device or a loupe on a light table to enlarge the image. If the film is larger, it can, when backlighted, be seen on its own. Whatever the original size, it can serve as the basis of a print. If it is to be made into a print, everything I’m about to say about negative and digital images applies to it as well.

The photographic print: mechanical issues

Pablo Casals (1938), Janos Starker (1965), Mstislav Rostopovich (1975), and Yo-Yo Ma (1983 and 1997) all used the same score for Bach’s Cello Suites; the performances vary in ways large and small. A musical score is a theory for a performance. The image recorded on film or in a digital file is a theory for a print in exactly the same way. As with musical performance, the results vary with the conditions of production and who is doing the work. Here are a few of the factors that affect the final print, some mechanical, some personal:

In the darkroom:

—the same negative printed on different papers can result in radically different images. The paper I primarily used in the darkroom days came in six grades: one end was high contrast, the other low contrast. (Some printing papers could produce a similar range when color filters of various grades were placed between the enlarger’s lens and the paper sheet.) The same negative of a face printed on #1 and #6 using the same exposure settings and same chemical baths would produce two very different images, one of them showing ever line, every discoloration, every shadow; the other showing smoothness and soft shading.

—the same negative printed with the same exposure settings on different enlargers could result in different images because of differences in the light provided by the enlarger and different optical performance of the enlarging lenses. Some light source/lens combinations provide perfectly even light hitting the print paper; some do not.

—the same negative printed with the same exposure in the same enlarger with the same settings might result in different prints if on one occasion the chemicals were fresh and another they were not, or if the temperatures in the chemical trays varied on different occasions.

In the darkroom or printing digitally:

—different printing papers have different tonalities: the surface might be brilliant white or warm white or somewhere between; it might be matte or glossy.

Printing digitally:

—Different printer brands render greyscale and colors differently.

—Printers with a few ink cartridges render images differently than printers with a lot of them.

All photographic images:

—look different under different lighting conditions: colors in a color print look different, and relate to one another differently under ordinary incandescent light, florescent light, daylight; the greyscale in a black and white print might seem different in those three situations. Ambient color temperature and intensity influences what we see.

—are conditioned by where we see them: in a print on a wall or on a table, in a well-printed art book, in an ordinary book, in a newspaper, projected on a screen, projected from a screen (monitor, smartphone).

All of those are variables inherent in the medium: what we see varies on how the image was made, the surface we’re seeing it on, the light we’re seeing it in.

Some great photographers – Henri Cartier-Bresson,

Walker Evans and Gary Winogrand among them–

rarely made their own prints. Sometimes

they had control over what the printer did;

more often they didn’t.

Some great photographers—Henri Cartier-Bresson, Walker Evans and Gary Winogrand among them—rarely made their own prints. Sometimes they had control over what the printer did; more often they didn’t. Paul Strand, as I noted in a previous article in this series, made all his own prints, and took the printing very seriously, until his final days, when he allowed Richard Benson to print for him. But he oversaw that printing. He did not have such intimate control over printing of his books, which he considered more important than his prints on gallery walls. Print photographers relying on color labs are totally dependent on the technicians in those labs; some of them work closely with the labs, doing many iterations until they “get it right”; others send the negative or file off and it’s someone else’s job, someone else’s problem.

The Photographic print: intentional issues

Then there are factors imposed on that intermediary record—the film or file—by the photographer or whoever else is making the print. I wrote above that the recorded image is a theory for a print. That is abstract, so let me offer two simple examples, one from Facebook, the other from a friend who documents solar flares.

Photo by Francesco Carrozini

The Facebook photo had this caption: “The hands of Keith Richard in 2008. Photo by Francesco Carrozini. ‘That photograph was originally in color and in fact I decided to change it to black and white afterwards. Not because it would have been more truthful but because to my eye it became more of a map of his life.’”

That sounds to me as if Carrozini really did think the black and white image was more truthful—not to the fact of the moment, but rather to what he thought his photograph was really about. For him, color in that photograph would have been a distraction, so he got rid of it and worked with the greyscale.

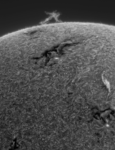

Alan Friedman

The other is by Alan Friedman, who has for some time been photographing the sun: spots, flares, tonality of the surface. He discovered that printing a negative image of the sun provided far more information than a positive image.

“In the ‘scientific’ imaging community,” he wrote me recently, “there is constant debate about what is fair game for manipulation. With Elon Musk’s Starlink satellites creating white lines through virtually any time exposure in the night sky, erasing has become commonplace.

Alan Friedman

My work was very controversial when I first began experimenting inverting the tonal values of the sun. The negative image shows depth and texture much more effectively that the positive captured image and since no one knew what the surface of the sun looked like anyway, it was a ripe fruit for manipulation.” When he sent the two photos here, he noted, “The experience of depth is easier to feel in the negative version.”

Those are two simple examples of rendering the recorded image in a way that makes it more useful, the first emotionally, the second functionally. Both address feeling, a quality that can be in and emanated by a photograph.

There is far more, in these days of digital image processing, that can be done. How much manipulation is legitimate? How much not? Using Photoshop to put someone’s head on someone else’s body, or a body in a place it isn’t, is usually considered not legitimate, save in a visual satire or gag when the manipulation is obvious, such as these two images, which were all over social media in the days after Donald Trump’s June 9, 2023, 37 felony-count indictment for mishandling government documents. Neither is a photograph. Things like these are pictures composed of parts of photographs and other images.

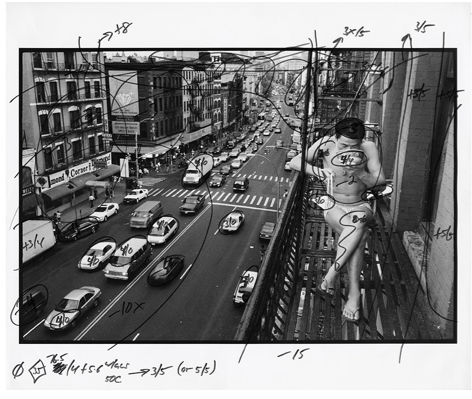

In the darkroom days, printers would give parts of an image more (burning) or less (dodging) light to preserve or bring out detail. Magnum, the photographer’s collective, recently had a sale of prints marked up for burning and dodging. I assume their purpose was to give people interested in photographic work some sense of what went into the productions of a master print. One was this 1998 printing map by Chien-Chi Chang:

That is a lot of darkroom work.

Every one of those adjustments had

to be done for every print.

Chien-Chi Chang

That is a lot of darkroom work. Every one of those adjustments had to be done for every print.

That wasn’t the end of it. Once the prints had dried, printers might use small fine brushes and sets of inks to “spot” prints—to get rid of defects in the negatives or blemishes on a face.

People working on digital images do the same thing, but they have far more options. They can brighten eyes, darken and defocus backgrounds. They can precisely select and work on any portion of the image. If the images are in color, they can tweak individual colors across the image or in this or that space. The fixes are saved in a digital metafile, so they don’t have to be redone for every print.

There is a tradeoff: every print pulled from that digital file will have exactly the same corrections; every hand-burned and -dodged print was, in ways small or large, unique.

About color and film speed

In the film days, the choice about black and white or color and about film speed (how much light a particular film needed to make a good image) was made before the shutter closed: the camera was loaded with one kind of film and no other. Now, with one exception, all digital cameras shoot color, and the decision to have the final image be in color or black in white is made at the processing screen, with a computer, a keyboard, a tracking device.

The exception is Leica, which currently has two digital models with sensors dedicated to black and white: the M11 Monochrom ($9195 for body only), and the Leica Q3 Monochrom ($5995, with fixed f 1.7 ASPH, 28mm lens). Both produce huge images and have an enormous range of light adaptability (M11M 60 megapixels, ISO 125-200,000; Q3 60 megapixels, ISO 50-100,000). In film, higher speed (EI or ISO) usually resulted in more grain in the negative: Kodak Plus -X (ISO 125) was smoother and less grainy than Kodak Tri-X (ISO 400). Most digital cameras are able to adjust their ISO, so they can work in a variety of lighting situations. Higher-end cameras are capable of producing smooth images over a great ISO range.

Why photograph?

For most photographers, the reason for making a photograph, is to have something to look at. It may be personal (travel, family); it may be professional (journalism, portrait, advertising); it may be artistic. Some photographers photograph just to be doing it and the prints at the other end are only incidental to the process. Vivian Maier left 150,000 negatives, a third of them undeveloped; a fraction of them printed in her lifetime. The great street photographer Gary Winogrand left 6500 undeveloped rolls (over 230,000 frames) and 300,000 unedited developed images. During his lifetime, he was content to let others print his pictures and select them for exhibitions. He liked to take pictures.

Four Bottom Lines

Any discussion of “Photography” is flawed from the start. We have to know what kind of photography is being discussed, and maybe a good deal more. What is good or meaningful for the street photographer is not good or meaningful for the combat or scientific or wedding photographer, and any commentator on photographic work who melds them all into a single porridge, as Sontag does, or who tried to find the essence undergirding them all, as Barthes does, misses that point. Or is making up a point that has no counterpart in the world of people making pictures.

As Gary Winogrand put it: “A photograph is not the thing photographed; it is something else.” If you’re going to philosophize about photographs, about photographic acts, Winogrand’s distinction is critical. I don’t think Roland Barthes got that, which I’ll get to in the next essay in this series.

As William Blake put it: “To Generalize is to be an Idiot. To Particularize is the Alone Distinction of Merit.” Sontag generalized “photography” into a meaningless goo. Every photographic image, in whatever medium, is as particularized as you can get.

I’ve generalized here. Mea culpa. Forgive me, William Blake. It’s difficult to avoid. Blake was doing it in that ukase I just quoted. The important thing is to be aware when you’re doing it, and take responsibility for it by going specific. As I have in the essays preceding these notes and shall in those to come.

Bruce Jackson is SUNY Distinguished Professor and James Agee Professor of American Culture at University at Buffalo. Some of his books are Places: Things heard, things seen (BlazeVox, 2019) Inside the Wire: Photographs from Texas and Arkansas Prisons (Texas, 2013), Being There: Bruce Jackson Photographs 1962-2012 (Burchfield Penney Art Center, 2013): Ways of the Hand; A Photographer’s Memoir (SUNY Press 2022).