Return to Theme Table of Contents

Return to VJIC Table of Contents

Return to VASA

“All my books”: Paul Strand’s Arc

Bruce Jackson is SUNY Distinguished Professor and James Agee Professor of American Culture at University at Buffalo. Some of his books are Places: Things heard, things seen (BlazeVox, 2019) Inside the Wire: Photographs from Texas and Arkansas Prisons (Texas, 2013), Being There: Bruce Jackson Photographs 1962-2012 (Burchfield Penney Art Center, 2013).

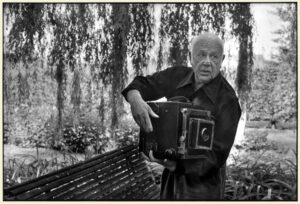

Paul Strand, the greatest of the modernist photographers, was born in New York City in 1890; he died in Orgeval, France, in 1976. His work had profound influence on, among others, Georgia O’Keeffe, Walker Evans, Ansel Adams (who thought he might become a piano player until he met Strand), and Edward Hopper. Strand, Alfred Steiglitz and Edward Weston were the three photographers most responsible for getting photography accepted as an art form in the United States.

During a two-year stint in Mexico (1933 and 1934), Strand’s aesthetic vision and sense of mission made a critical pivot. It would take him several years to know what to do with it.

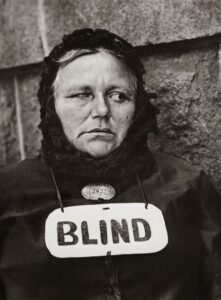

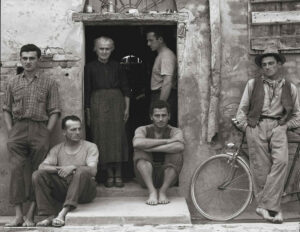

He is best known for some of his single images: “Wall Street” (1915) “White Fence” (1916), “Blind Woman” (1916), and “A Family” (1953). They are great images. But they’re not what he, finally, thought his work was really about.

Wall Street |

White Fence, 1916 |

Blind Woman. 1916 |

Family, 1915 |

Finding Focus

Louis Hine, one of the first people to use photography to effect social change, was Strand’s first photography teacher, and it was he who introduced Strand to Alfred Stieglitz. In 1907, Hine took his Ethical Culture High School class to Steiglitz’s 291 Gallery, where Strand saw what the best current photographers were up to — on the same walls as Picasso, Braque and others of the European avant-garde. Photography was not only interesting, but it existed in what poet Robert Creeley would later call, that “company”: people who were speaking the same language and discovering that fact when something brought them together and they heard not cacophony, but harmony or concert.

In a 1974 New Yorker interview, Strand told Calvin Thomas that the 1913 New York Armory show—1300 works by 300 avant-garde artists—gave him a new understanding of “what a picture consists of, how shapes are related to each other, how spaces are filled, how the whole must have a kind of unity.” Speaking of a photographing trip to Nova Scotia: “I couldn’t have done the rocks without having seen Braque, Picasso, Brancusi. I used a sharper lens. I never went back to soft-focus.” That perception would inform his work for the rest of his life.

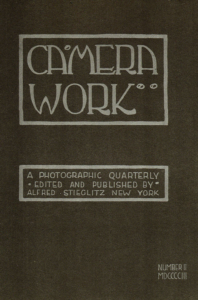

Camerawork

“…In 1915,” Strand said, “I really became a photographer. I had been photographing seriously for eight years, and suddenly there came that strange leap into greater knowledge and sureness. I brought a group of my things in to show Stieglitz, and when I opened up my portfolio, he was very surprised. I remember he called to Edward Steichen, who was in the back room at ‘291,’ and had him come out and look, too. Stieglitz said, ‘I’d like to show these.’ He also told me that from then on I should think of ‘291’ as my home, and come there whenever I wanted. It was like having the world handed to you on a platter. It was a very great day for me, matching, in a sense, the day that Hine took us to Photo-Secession and I saw the work of those other photographers for the first time.”

“… It was a very great day for me, matching, in a sense, the day that Hine took us to Photo-Secession and I saw the work of those other photographers for the first time.”

Stieglitz would give him his first one-man show in 1916 and would devote the final issue of his influential magazine, Camera Work, entirely to Strand a year later.

Like other Pictorialist period photographers, Strand’s early work often seemed to be photographs trying to be paintings. (Which is curious because photography freed painting from having to be realistic. Modern art, I think, begins with the invention of the camera). After the 1913 Armory show, he begins making photographs that are abstract or might as well be. He never, I think, ever left any of the earlier imagination behind; it blended into his expanding sense of the social significance of what he was seeing and photographing.

He photographed carefully and deliberately, but he refused to be victim to his negatives. They were starting points. “I’ve always felt you can do anything you want in photography if you can get away with it….,” he told Tomkins. “There was one group of three people that should really have been two people. I took the third person out. Retouched him out in the darkroom. I had no great feeling of guilt over that. Of course, I don’t agree with this method of just shooting and shooting and hoping to find something later in the darkroom. I’ve done all sorts of retouching when there’s been a functional reason for doing it, and I crop negatives in the enlarger all the time. In general, I agree with Cartier- Bresson, who says he always used the whole negative. That’s the best way to work. It’s only when you know how to work that way that you have the right to crop. But it’s not a great issue. The only great issue is the necessity for the artist to find his way in the world, and to begin to understand what the world is about.”

There are some documentary photographers who privilege the moment the shutter closed, and mark it by publishing photographs framed by the negative’s unexposed borders, which prints as an uneven black frame line. Those black frame lines proclaim: “Uncropped!” Robert Frank, for example, did it in The Americans (Grove Press, 1959), as did Danny Lyons in Conversations with the Dead (Macmillan, 1968). Photographers like Strand and Walker Evans would have none of that. Evans went so far as to scissor-cut some of his large format negatives to ensure no later editor could print parts of the original capture he thought irrelevant.

In his early work in New York, Strand often used a clumsy device under his arm so people wouldn’t realize his lens was pointed at them.

Spylens, a reflected 90 degree view

In his later work—in Mexico, the Hebrides, Italy and elsewhere, he used a prism to do the same deception more economically. (He wasn’t the only one doing that: painter Ben Shahn used a prism lens when he worked for the Farm Security Administration in the 1930s. There is a Shahn photo of two men; in the window you see Shahn in profile, presumably pointing his camera down the street. Walker Evans would use one, and so would Helen Levitt. That stuff would be considered unethical by most photographers now, but there’s a modern equivalent: pretending to be reading on a smartphone or tablet while actually taking pictures with the device.)

Strand told Tompkins: “I never questioned the morality of it. I always felt that my relationship to photography and people was serious, and that I was attempting to give something to the world and not exploit anyone in the process. I wasn’t making picture postcards to sell.”

Even inanimate objects were in service to that vision. “‘White Fence’ was fascinating to me,” he said. “It was very alive, very American, very much part of the country. You wouldn’t find a fence like that in Mexico or Europe.” He said he’d seen a fence in Russia he thought would have been Dostoievskian. “That fence, and those dark woods, gave the same sort of feeling you get in reading ‘The Idiot.’ You see, I don’t have any aesthetic objective. I have aesthetic means at my disposal, which are necessary for me to be able to say what I want to say about the things I see. And the thing I see is outside of myself—always.’”

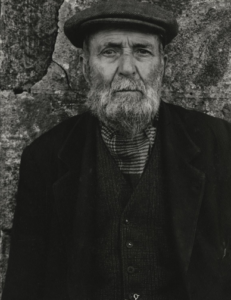

That sentence, perhaps, expresses best how he differs from Stieglitz and Weston. He became a realist, not an aesthete or documentarian. He wanted to capture what he thought the essence, the reality, of the people and places he photographed. He was as willing to manipulate the facts of the moment as he was to tinker with his negatives in prints: he put a hat on a girl in Italy was not hers; he posed a man in the against a wall that was not his wall. But the photo was that girl, in that place, and that man, in that place, and they all were Strand’s sense of what the life and place were really about.

Girl With Hat |

Man in Hebrides |

New Mexico and Old Mexico

Rebecca

In 1926 he visits New Mexico; he returns in the summers of 1930, 1931, and 1932. He photographs his wife, Rebecca Salsbury, and friends John Marin, and Georgia O’Keeffe. There is one church in Taos that he photographs and O’Keeffe and Marin paint many times. He also does landscapes, seeking the harmony he began to understand in the 1913 Armory show, and that he is less and less finding in his home. He took more than 100 photos of Rebecca between 1920 and 1932. Over that time, as Belinda Rathbone astutely noted, the photos of Rebecca become more and more distant. He took the photos as portraits, but in sequence they became a visual narrative of their decaying relationship.

There are also photographs from before the New Mexico period by Stieglitz, nudes of Rebecca that are very much like what Stieglitz would shoot of O’Keeffe. Steiglitz, for all his aestheticism, seemed to like taking photographs of women with big breasts holding them up for his camera.

Strand would later destroy many of his own negatives of Rebecca. His correspondence to her is lost (hers to him, including some letters in 1929 about her affair with Georgia, survive). After their relationship ended in 1933, he never did personal photographs again.

He is grows ever more political, and that is one of the reasons his professional relationship with Stieglitz is begins to fray. “During this period,” wrote Steve Yates, “he grew closer to Harold Clurman, a founder of the Group Theater in NY and drew away from Steiglitz. Clurman offered something Stieglitz didn’t: a connection between art and social awareness. Clurman wrote in one letter, ‘[Stieglitz] cannot see anything as an object outside, separated cut off from himself. (You can and do: which is one of the essential differences in your photographs)…. In Stieglitz there is no revolt, no social attitude: always a spontaneous acceptance—unquestion—for what is there. In you (your photographs) the object is seen as having a distinct but separate life of its own—and a very powerful immovable life, untouched and untouchable by man.”

Women of Santa Ana, 1933

In 1933, composer Carlos Chavéz invites him to Mexico. The Mexican Revolution had run over a decade (1910-1920) and it was in the 1930s that the new world was supposed to be taking shape. It seemed a perfect fit for his increasing political awareness. Rebecca accompanies him, but leaves after three months; they divorce later that year.

Mexico, Girl and Child 1933

He has an exhibit in Mexico City of his photographs from New Mexico, Canada and Maine; he teaches in a school; he takes some photographs. And then gets involved in what is supposed to be a five-film series, but turns out to be just one: Redes, a fiction film about fishermen organizing. Redes prefigures Italian neo-realism: with one exception, none of the actors are trained; the locations are all real. The nominal director was Fred Zinneman, but, as William Alexander wrote, Strand was the film’s guiding genius: “Strand conceived the film, supervised the entire production, and served as cameraman on all except the water close-ups. The film is very much a Strand film.”

The political aspect of Strand’s art matured in Mexico, but there was another, more important change: he became multidimensional and polyphonic. Photographs are this and this and that. Film is ineluctably serial; it has images and perhaps words and sounds and music. There is no pause; there is no entering the gallery from the right or left; there is no photo on the verso and another on the recto. You can walk around a gallery however you like; you can page through a book at your own pace and, when the mood strikes, go back to an earlier page or pause to do something else. Film manifests itself in real time, and in film time, the arrow goes only in one direction, totally commanded by what Orson Welles called, “That ribbon of dream.” The great Russian director Andrey Tarkovsky titled his book about film Sculpting in Time. Photographers stop time; filmmakers inhabit it.

Redes (filmed in 1933; released in 1936) was grounded in a story. Strand’s images are beautiful; Silvestre Revuletas’ score is beautiful. But the film is grounded in the narrative, in sequence, in time.

That wasn’t Strand’s first encounter with film. He had made Manhatta, a silent experimental film with Charles Sheeler in 1921. It had intertitles from Walt Whitman’s “Manahatta.” From 1922 to 1932 he had worked as a freelance cameraman for other people’s sports and medical films. He even worked on some Hollywood films.

But Redes was his first deep involvement with narrative film. After it, he would do no still photography for a decade. Instead, he told stories in film. He was a cinematographer for Pare Lorentz’s The Plow that Broke the Plains (1936) and then one of the organizers of Frontier Films, which, according to Amanda N. Bok, “produced eight films. Most were two-reel shorts and under twenty minutes in length that addressed social, labor, political, human rights, and environmental issues.” The only full-length film produced by Frontier was Native Land, a film about union-busting, directed by Strand and Leo Hurwitz, with narration by Paul Robeson. The 88-minute film was released in May 1942, six months after Pearl Harbor, a time when no one wanted to hear about problems and injustice in the industrial complex. (A similar fate befell James Agee’s and Walker Evans masterpiece, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, a book about tenant farmers in rural Alabama published in late 1940. The U.S. was then gearing up for war, the Depression was over and there was little interest in poor farmers. The book didn’t find an audience until it was reprinted in 1960.)

Strand returned to still photography in 1943 when there was no more money for the kind of films he wanted to make. He continued doing photography for the rest of his life, but the work he did was conditioned by the multivocality he’d come to appreciate in his narrative film years.

The Books

He was, at that point known as the creator of some photographic masterpieces, but he was better known for his film work. That changed in 1945, when Nancy Newhall, then acting curator of photography at Museum of Modern Art, gave him a retrospective, Paul Strand: Photographs 1915-1945: 172 prints, and a large catalog. That was MoMA’s and Strand’s first photographic retrospective. It was also the first time an entire book was devoted to his work. The show included his work in New York, New England, the Gaspé Peninsula, and Mexico. He had been in many exhibits previously, but this show, for the first time, showed his scope.

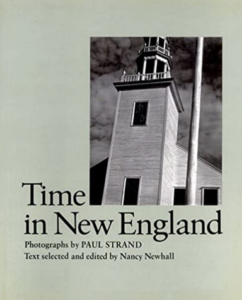

After the show, Newhall suggested they collaborate on a book, a collage of New England voices combined with his photographs. He agreed and went off for a year or two, shooting more.The resulting book, Time in New England (1950), gave Strand the voice he had sought for a decade, a way to publish his photographs in the world they portray. Newhall selected all the texts and even suggested some subjects for him to photograph. Time in New England is polyphonic. Strand’s photos are juxtaposed to texts by John Winthrop, William Bradford, Anne Bradstreet, Roger Williams, Cotton Maher, John Adams, Samuel Adams, Emerson, Melville, Thoreau, Emily Dickinson, Hawthorne, Margaret Fuller, Robert Frost, Winslow Homer, Sacco and Vanzetti, and others. The texts are ranging and almost encyclopedic, as are the photographs.

After the show, Newhall suggested they collaborate on a book, a collage of New England voices combined with his photographs. He agreed and went off for a year or two, shooting more.The resulting book, Time in New England (1950), gave Strand the voice he had sought for a decade, a way to publish his photographs in the world they portray. Newhall selected all the texts and even suggested some subjects for him to photograph. Time in New England is polyphonic. Strand’s photos are juxtaposed to texts by John Winthrop, William Bradford, Anne Bradstreet, Roger Williams, Cotton Maher, John Adams, Samuel Adams, Emerson, Melville, Thoreau, Emily Dickinson, Hawthorne, Margaret Fuller, Robert Frost, Winslow Homer, Sacco and Vanzetti, and others. The texts are ranging and almost encyclopedic, as are the photographs.

“Strand had discovered the book format” wrote Amanda N. Block, “a medium that held the promise of upholding uncompromising artistic standards while still reaching great numbers of people, and this would remain his preferred method for presenting his work to the public for the rest of his career.”

The same year, Strand moved to to Paris because of the repressive political climate in the United States. He worried the FBI was watching him. He wasn’t paranoid: the FOIA file on him shows they kept tabs on him for 30 years.

He will do several more projects, not all of which will work out. He’ll shoot in Rumania and Morocco. Those result in some good photos, but not books. The five books that are achieved are each about a different place, each with a political motivation, each in collaboration with a writer, each different in writerly style.

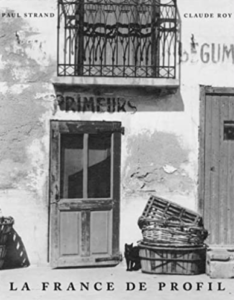

The first of these was La France de Profil (1952) with Claude Roy. He wanted to document a village—something like Spoon River Anthology by Edgar Lee Masters, a book he loved. He didn’t find the village, so he did the country.

Next was Un Paese: Portrait of an Italian Village (1955), with text by Cesare Zavattini. This is the book in which, I think, it all worked. Zavatttini’s text was at points descriptive, historical, poetic, vocal. Strand called it “a film on paper.” (In 2001, one of Strand’s prints of the best-known photo from it, “The Family,” sold for $281,000 at Southeby’s).

I noted earlier that Redes, pre-figured Italian neo- realism films. Strand loved De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves and Rossellini’s Rome Open City. Zavattini was the perfect partner for this book: He had been born in Luzarra in northern Italy in 1902; he had written scripts for De Sica’s Shoeshine, Bicycle Thieves, and Umberto D. He also worked with Antonioni, René Clement, Fellini, Rossellini, and Visconti. He and Strand had met at a film conference in Perugia in 1949 and had immediately connected.

The text in Un Paese is not synchronous with the photos. For example, a bent old man in Luzarra is recto; verso are bent old intertwined vines. Zavattini’s text underneath is, “I’ve always worked as a ploughman and I’ve lived at the old people’s home since I turned seventy. I never married and I’m comfortable here at the home. There are old women here who always argue, but now the Sister has gotten them to sing, and they have a choir and don’t argue anymore.” Who knows who is speaking? Who knows when the photo was made? The book is a duet, but one in which the two artists created and performed their parts at different times in different places: Zavatttini did his text after he saw Strand’s images; the two worked out the final configuration.

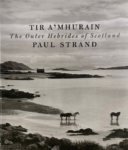

Next was Tir A’Mhhurain: Outer Hebrides 1962 (US 1968), with text by British poet by Basil Davison. Strand had done the photos earlier: in 1954 , after he learned that the U.S. was planning to build a nuclear missile base there, he spent three months trying to capture the people, the place and the texture before the inevitable change. It was, in a way, a photographic eulogy for a death that hadn’t yet occurred.

Next was Tir A’Mhhurain: Outer Hebrides 1962 (US 1968), with text by British poet by Basil Davison. Strand had done the photos earlier: in 1954 , after he learned that the U.S. was planning to build a nuclear missile base there, he spent three months trying to capture the people, the place and the texture before the inevitable change. It was, in a way, a photographic eulogy for a death that hadn’t yet occurred.

He moved from Paris to Orgeval in 1955. There, he built his first permanent darkroom with his first enlarger. Before that, he’d mostly done contact prints from his large- and medium-format negatives, used other people’s darkrooms, or found makeshift ways to do his prints. He also began photographing the garden. That same year, his U.S. passport was revoked because of his political activities, preventing him from traveling outside of France, so he began a series of French portraits: Braque, Picasso, Simone de Beauvoir, Sartre and others. (The U.S. eventually not only gave him his passport back, but twice invited him to White House events. He declined both invitations because of his opposition to U.S. involvement in Viet Nam.)

He would do two more book projects. Living Egypt (1969), with text by James Aldridge, was based on photos he had been done a decade earlier, a period when Egypt had transitioned from a monarchy to a country with an elected president. The other was Ghana: An African Portrait (1976) with text by Basil Davidson. He’d done the photos in 1963 and 1964, when Ghana had just got out from British colonialism and was developing industrially. W.E.B. DuBois’s wife, at Strand’s request, had asked President Kwame Nkumrah to invite him.

|

|

The projects, as the Mexican work, all had a political context, but Strand was an artist, not a polemicist. He knew the difference between political action and making photographs. In each of these books, he was presenting not only photographs, but contexts. He was an artist who could find human context in stones.

The Aperture Connections

Major recognition came late. During the anti-communist witch hunt days, his books were hard to find in the U.S. He applied for four Guggenheims and at least one Fullbright fellowship; he was turned down for all of them.

In 1964, Michael Hoffman, took over the moribund photography magazine Aperture. (Nancy Newhall had been one of the founders). Hoffman began a book series. He would, during his time there, produce more than 300 volumes: work by Diane Arbus, Edward Weston, Dorothea Lange and others. And Paul Strand. A lot of Strand. Their relationship began when Hoffman wrote Strand to ask if Aperture could reprint Time in New England. He would curate the huge 1971 Strand retrospective at the Philadelphia Museum of Art—440 prints (only 2 of Rebecca), and would become the executor of Strand’s estate. The two-volume catalogue for the 1971 show was the most expensive photography book ever published to that point. Strand spent two years preparing the prints.

Strand dedicated the first volume of the catalog: “To Jacob Strand, my father, whose faith in my work never faltered from its beginnings to the time of his death in 1949. When photography as an art medium was still new and unaccepted, he did not doubt its possibilities nor question his son’s choice of a life work. This faith, so simple and clear, is reflected in this book.” He dedicated the second volume to his wife, Hazel, who was an essential part of the late part of his career. During the travels for the books, she arranged everything; when he was almost blind from cataracts, she helped him make prints, telling him what she was seeing in the darkroom; she spotted his prints. Many of the prints in the Philadelphia Museum of Art collection of Strand’s work bear, in addition to his signature, the initials “H.S.” Those are prints from that astonishing collaborative period.

Strand dedicated the first volume of the catalog: “To Jacob Strand, my father, whose faith in my work never faltered from its beginnings to the time of his death in 1949. When photography as an art medium was still new and unaccepted, he did not doubt its possibilities nor question his son’s choice of a life work. This faith, so simple and clear, is reflected in this book.” He dedicated the second volume to his wife, Hazel, who was an essential part of the late part of his career. During the travels for the books, she arranged everything; when he was almost blind from cataracts, she helped him make prints, telling him what she was seeing in the darkroom; she spotted his prints. Many of the prints in the Philadelphia Museum of Art collection of Strand’s work bear, in addition to his signature, the initials “H.S.” Those are prints from that astonishing collaborative period.

In 1972, when Strand became ill with bone cancer, Hoffman convinced him to let Richard Benson (1943-2017) print for him. (Benson also printed for Walker Evans). It was the only time Strand ever let anyone else make photographic prints from his negatives.

They worked on four portfolios, none published while Strand was alive. On My Doorstep consisted of eleven prints drawn from each of the decades in which Strand had photographed; The Garden consisted of six prints of his own garden. In the introduction to On My Doorstep, Strand wrote: “Finally it can be seen that what I have explored all my life is the world on my doorstep…. The material of the artist lies not within himself nor in the fabrications of his imagination, but in the world around him. The element which gives life…is the relationship of artist to content, to the truth of the real world. It is the way he sees this world and translates it into art that determines whether the work of art will become a new and active force within reality, to widen and transform man’s experience. The artist’s world is limitless. It can be found anywhere, far from where he lives or a few feet away. It is on his doorstep.”

They worked on four portfolios, none published while Strand was alive. On My Doorstep consisted of eleven prints drawn from each of the decades in which Strand had photographed; The Garden consisted of six prints of his own garden. In the introduction to On My Doorstep, Strand wrote: “Finally it can be seen that what I have explored all my life is the world on my doorstep…. The material of the artist lies not within himself nor in the fabrications of his imagination, but in the world around him. The element which gives life…is the relationship of artist to content, to the truth of the real world. It is the way he sees this world and translates it into art that determines whether the work of art will become a new and active force within reality, to widen and transform man’s experience. The artist’s world is limitless. It can be found anywhere, far from where he lives or a few feet away. It is on his doorstep.”

The Work

Paul Strand’s photographs through his entire career comprise a great achievement and the presentation of them is the realization of that. Strand’s key insight in middle age was that for the work he wanted to do, it was not the gallery wall, it was not the sellable print, it was the book, with all those words in all those styles and formats before and after and adjacent. The books are silent movies you can hold in your hand with words you can hear in your mind.

The books are silent movies you can hold in your hand with words you can hear in your mind.

Paul Strand

Catherine Duncan, a close friend who worked with Strand organizing his negatives and prints in the final years, wrote: “Three nights before he died, Richard [Benson] kept watch in the shadowy bedroom where Paul lay. Once the fourth portfolio had been approved, Paul refused to eat or drink. For over a week he had been in a semi-coma. The house slept and no sound came from the garden. Suddenly, Paul sat upright in bed, his eyes wide open, and cried out his final word: All my books!”

Acknowledgements and sources

This essay grew out of a talk I gave about Strand’s work at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo on October 15, 2015, “Paul Strand: Genius of Form, and the Discovery of Context.” The talk was a component of a three-day Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra event celebrating Aaron Copland’s influence in Mexico and his blacklisting during the McCarthy era. The event included a screening of the film Redes (1933) with a live performance of the film’s score by the BPO. My thanks to the Albright-Knox Art Gallery director Louis Grachos and senior curator Douglas Dreishpoon, and BPO conductor and musical director JoAnn Faletta for inviting me to participate in that event.

My thanks also to Peter Barberie and his staff at the Philadelphia Museum of Art for helping me spend two days looking through prints by Strand from his work in Mexico and the Outer Hebrides.

And to Diane Christian, for her careful reading of this article and her memory of our visit to the 1971 Philadelphia exhibit of Strand’s work.

Much of this essay draws on:

Paul Strand: Master of Modern Photography. Philadelphia Museum of Art and Yale University Press, 2014. A catalog for the 2014 Strand exhibit at the PMA. It includes, among other interesting items, essays by Barberie and Amanda N. Bok, a “Roundtable Discussion about Strand’s Later Work,” and a superb chronology by Bok.

Paul Strand: Aperture Masters of Photography, Aperture, 2014. Includes introduction and commentary on Strand and the photos by Peter Barberie.

Paul Strand: Sixty Years of Photography, Aperture, New York, 1976. Includes a detailed chronology and Calvin Tomkins’ 1974 New Yorker interview.

Philadelphia Museum of Art: Paul Strand: A Retrospective Monograph. The Years 1915-1968. Aperture, 1971.

Belinda Rathbone: Portrait of a Marriage: Paul Strand’s Photographs of Rebecca,” J. Paul Getty Museum Journal, 17 (1989), pp. 83-98 .

Maren Strange, ed.: Paul Strand: Essays on his Life and Work, Aperture, 1990. Particularly Steve Yates, “The Transition Years: New Mexico,” 87-100; Richard Benson, “Print Making,” 103-108; and William Alexander, “Paul Strand as Filmmaker, 1933-1942” 148-160. This collection also includes Paula Rathbone’s “Portrait of a Marriage” (72-86).

Strand’s films and films about Strand online:

Manhatta (1921, with Charles Sheeler) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qduvk4zu_hs

The Plow That Broke the Plains (Pare Lorenz, 1936 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hzaV5FdZMUQ

Redes (1936). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_bK54w6hkuY

Martin Scorsese on Redes: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iI92alJhq08

REDES Lives! The Iconic Film of the Mexican Revolution—and what it says to us today (visual presentation by Peter Bogdanoff; scripted and edited by Joseph Horowitz. 2020): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1gnQakMpj4g

John Walker: Photographer Paul Strand Under the Dark Cloth 1989 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J0Fieteq2Pk&t=33s A dreadful 81-minute feature: none of the speakers are identified, a lot of key facts are absent, the music is relentless and uneven, and it’s often out of sync. But there is some great footage of Strand, his co-workers, his friends, and his wives.

The web page posted by the Philadelphia Museum of Art on the occasion of the 2014-2015 exhibit, Paul Strand: Master of Modern Photography, contains a chronology and many images.

Ways of the Hand: A Photographer’s Memoir (SUNY Press, 2022)