Return to theme table of content

Return to VJIC table of content

Jewish Photographic Perspectives Part 1

© Robert Hirsch 2022

VASA Journal on Images and Culture (VJIC), Theme Editor and Writer

“If photography is to be discussed on a serious level,

it must be described in relation to death.”[i]

Roland Barthes

This essay explores two Jewish photographers, Roman Vishniac and Mendel Grossman, who made pictures of Jewish and resistance life and death leading up to and during the Holocaust. Faye Schulman, Francisco Boix, the Sonderkommando, and Henryk Ross will be covered in upcoming essays. Through the lenses of a few we see many.

Note: Additional information about the images can be found at the end of this essay. Images have been minimally adjusted to facilitate online viewing, but have not been edited from their source.

A Jewish ghetto or shetl (Yiddish for town) existed everywhere there was a Jewish minority. This was the result of the acute antisemitism that led to the expulsion of Jews from England and Spain. Forced to live in these ghettos, Jews were treated as third class citizens who could be abused, beaten, robbed, and murdered at will.[ii] This ghettoization left the Jews without escape routes from the murderous Nazis; only a small number were able to safely immigrate to other countries.

As noted in the previous essay, much of the Nazi photography involving Jews was used for propaganda. The intent was to create a bestial representation of those defined by the 1935 Nuremberg Race Laws as Jewish, which legally defined Jews as a separate, non-white race.[iii] The starvation and suffering of ghetto residents was attributed to “rich Jews” who, according to the Nazis, refused to share their wealth with their less fortunate comrades. In an unnerving, ghastly way, the official Nazi photographs asserted that the Holocaust and the destruction of Yiddish culture was of the inhuman Jews’ own making.

3.0 Mendel Grossman Archive Tattooed Child, 1940—1944.

Yad Vashem: The World Holocaust Remembrance Center, Jerusalem, Israel.

Yet, despite the biblical injunction, “Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image,” Jews have played important roles in the history of photography and the recording of their civilization.[iv] In much of Europe, Jews had been denied citizenship and were barred from holding posts in government and the military, and excluded from membership in guilds and the professions. As photography was a new field with few gatekeepers, Jews began actively participating both on the professional and amateur levels.[v]

Roman Vishniac: The Eastern Front

The majority of Jews in prewar Europe resided in eastern Europe.[vi] In 1935, the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC or Joint) hired Roman Vishniac to travel throughout this region to make photographs documenting Jewish poverty and relief efforts for use in its fundraising campaigns. Posing as a traveling fabric salesman, Vishniac photographed the Jewish shtetlekh of Poland, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Russia, and Ukraine, which were by imperiled by both change and Nazi threats, on the eve of the Holocaust (1935–1939). Working under challenging internal and external circumstances, Vishniac said at times he carried a Leica, Rollieflex, movie camera, and tripods weighing 115 pounds (52 kilograms).

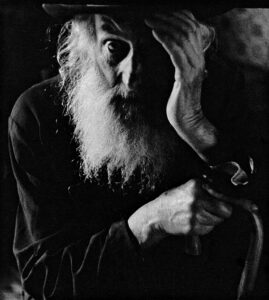

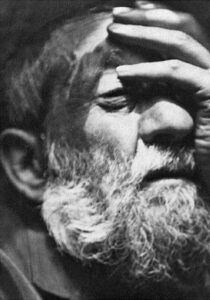

Figure 3.1 Roman Vishniac. Old Man, Carpathian Ruthenia, circa 1935–1939. © Mara Vishniac Kohn, courtesy International Center for Photography, New York.

Vishniac clashed with Orthodox Jews who refused to be photographed, citing the Bible’s prohibition of making graven images. His retort was, “the Torah existed for thousands of years before the camera had been invented.” Such reluctance lead Vishniac to utilize a hidden camera, which accounts for some of his happenstance results.[vii] In addition, he was detained numerous times for taking pictures, as authorities thought he could be a spy. Nevertheless, Vishniac carried out his photographic mission. After the German invasion of France, he was arrested and sent to an internment camp. Fortunately, his wife secured his release and he and his family immigrated to New York in 1940. Before his arrest, Vishniac hid his photographs with family and friends. Vishniac recounted:

I sewed some of the negatives into my clothing when I came to the United States in 1940. Most of them were left with my father in Clermond-Ferrand, a small city in central France. He survived there, hidden. He concealed the negatives under floorboards and behind picture frames.[viii]

Figure 3.2 Roman Vishniac. Granddaughter and Grandfather, Warsaw, circa 1935–1939. © Mara Vishniac Kohn, courtesy International Center for Photography, New York.

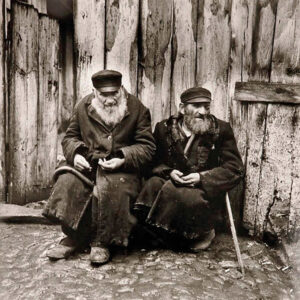

Figure 3.3 Roman Vishniac. Antisemitic Boycotts Changed Peddlers Into Beggars, Łódź, Lublin, or Warsaw, circa 1935-1938. © Mara Vishniac Kohn, courtesy International Center of Photography, New York.

Regrettably, of the 16,000 Vishniac photographs, only 2,000 reached America.[ix] Upon arriving in New York, Vishniac tried to exhibit these photographs and alert President Roosevelt to what was happening to European Jews. His efforts were met with indifference. Vishniac’s photographs gained recognition only after the Holocaust and were published in numerous books, including Polish Jews: A Pictorial Record (1947), Vanished World (1983), To Give Them Light: The Legacy of Roman Vishniac (1995), and Children of a Vanished World (1999).

In hindsight, Vishniac has been criticized for not keeping accurate records and not photographing well-to-do Jews. Also, Vishniac is known to have exaggerated the captions of his photographs, and, in some cases, may have fabricated the stories behind them. It is unfortunate that Vishniac did not provide details about those whom he photographed, as we know more about the monsters than the innocents of the Holocaust—the Germans kept meticulous records of their atrocities.

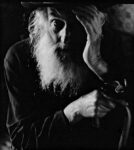

Figure 3.4 Roman Vishniac. Chaim Simcha Mechlowitz, circa 1935–1938 in Vysni Apsa, Carpathian Ruthen. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC.

These points are worth considering when evaluating Vishniac’s work, but it is also a case of applying contemporary intent and values on the past. One should bear in mind the circumstances surrounding the making of these his photographs. Vishniac’s mission was to make a visual record of a vanishing culture to raise funds for needy, vulnerable people and sound the alarm of their impending doom. Vishniac took chances to make these images, such as sneaking into Zbaszyn, an internment camp in Germany, where Jews were being deported to Poland. He made photographs of the “filthy barracks,” which he sent to the League of Nations to prove the existence of such camps that the Germans had denied. This was critical, as the public and the media had dismissed such accounts owing to the abundance of specious WW I propaganda to which they had previously been subjected.[x]

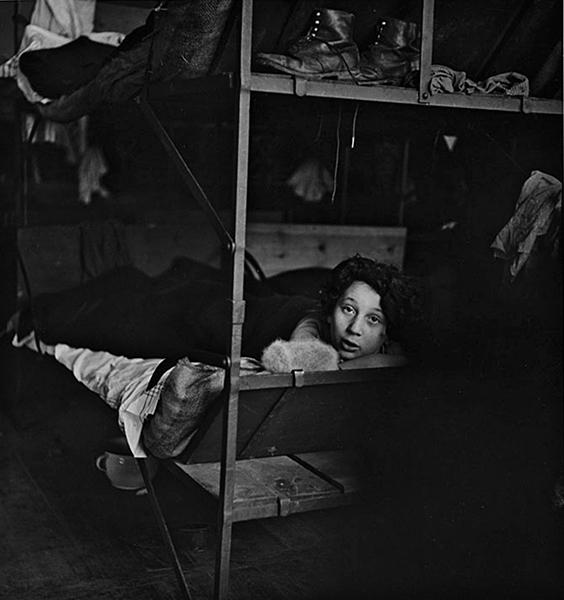

Figure 3.5 Roman Vishniac. Nettie Stub (age 11 from Hanover, Germany, in the Polish detention camp Zbaszyn), November 1938. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC.

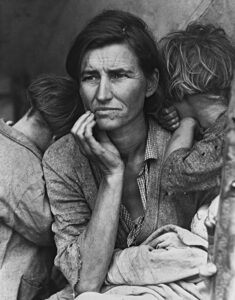

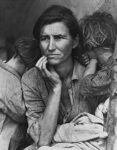

Most importantly, Vishniac was a story teller on a specific mission, not a conventional journalist concerned with the traditional Five W’s: the Who, What, Where, When, and Why of an event. Vishniac’s photographs were an emotional response to those who clung to their traditions in spite of ongoing oppression. He poignantly emphasized children since they represent the yet-to-come. This is why, in their attempt to ensure Judaism had no future, the Nazis murdered over a million Jewish children. In a similar manner and time frame, the US Farm Security Administration (FSA) commissioned photographers such as Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, and Gordon Parks to photograph sharecroppers and migratory agricultural workers in an effort to increase public awareness and gain emergency funding for their plight during the Great Depression and Dust Bowl of the 1930s.[xi] Observe the common humanistic approach of Lange’s icon Migrant Mother (1936) with Vishniac’s and know that Lange posed the principal subject and later had the print retouched.[xii]

Figure 3.6 Dorothea Lange. Migrant Mother – Florence Owens Thompson (unretouched), 1936. Library of Congress, Washington, DC. |

Figure 3.7 Roman Vishniac. Talmudic Scholar, Kraków, circa 1935–1939. © Mara Vishniac Kohn, courtesy International Center for Photography, New York. |

Even if Vishniac’s accounts were not literally accurate, they nevertheless convey an accurate interpretation of a slow-motion massacre. While Vishniac portraited his subjects in a sympathetic manner, there is nothing uplifting in these photographs, for they are about dead Jews and the bereavement of European Jewish culture (85% of those murdered were Yiddish speakers). Although the Holocaust has become a universal symbol for any major tragedy, Vishniac’s photographs remind us that the Jews were the primary target of Nazi extinction. Yet, in spite of all this, Vishniac’s photographs of eastern European Jews’ miserable circumstances do preserve their identity as a highly-literate society and serve as remnants of a world extinguished by real life demons.

Figure 3.8 Roman Vishniac. Cheder Boy, Carpathian Ruthenia, circa 1935–1939. © Mara Vishniac Kohn, courtesy International Center for Photography, New York.

Mendel Grossman: The Łódź Ghetto

Mendel Grossman (aka Grosman) was a Jewish photographer who worked in the photographic laboratory of the department of statistics in the Łódź (Litzmannstadt) ghetto.[xiii] In this position, he and and his assistant, Arie Princ (who changed his name to Aryeh Ben Menachem after moving to Israel and who very likely took some of the photographs), made identification cards and documented the work of his fellow inmates. The Ghetto Government wanted to believe that photographs that demonstrated the value of their slave labor would convince the Nazis not murder them. Grossman’s job allowed him to have a camera, Jews were forbidden to have cameras, that he hid in his clothing to illegally make more than 10,000 pictures of the ghetto conditions from early 1940 to its liquidation in 1944.

Figure 3.9 Aryeh Ben Menachem. Grossman at the Rubble of Łódź Synagogue, Wolborska Street, circa 1940. Yad Vashem: The World Holocaust Remembrance Center, Jerusalem, Israel.

He kept his hands in his pockets, which were cut open inside, allowing him to control the camera. He pointed the lens by turning his body in the direction he wanted, then slightly parted his coat, and pressed the shutter. Making these photographs put him at double jeopardy from the Gestapo that suspected his photographic actions, but also because he suffered from a severe heart ailment that was stressed by his relentless, physical photographic activities that included climbing on roof tops, electric power posts, and church steeples.

Grossman’s desire was to make a photographic record to be exhibited as testimony to the inhuman treatment of ghetto slaves, thus providing a bridge from demise to a future genesis. The ghetto community understood this necessity and embraced his photographing their daily existence. In a show of support, one ghetto workshop secretly constructed a telescopic lens. This allowed him to photograph events from a distant hiding place, such as the human convoys herded to the death trains.

Figure 3.10 Mendel Grossman. Corpse of a Jewish Man Murdered during Deportation, 1942.

Yad Vashem: The World Holocaust Remembrance Center, Jerusalem, Israel.

Figure 3.11 Mendel Grossman. Saying Goodbye, 1942.

Yad Vashem: The World Holocaust Remembrance Center, Jerusalem, Israel.

A heartbreaking example of this community motivation to leave a record is revealed in an incident in which Grossman encountered an entire family lugging a wagon filled with excrement through a street. Mendel hesitated to photograph such degradation. However, the father asked Mendel to photograph them saying:

Let it remain for the future,

let others know how humiliated we were.[xv]

Figure 3.12 A Mendel Grossman. Scheisskommandos (shit,commando)1940—1944. Yad Vashem. The World Holocaust Remembrance Center, Jerusalem, Israel.

Figure 3.13 Mendel Grossman Collection. Scheisskommandos, 1940—1944.

Yad Vashem. The World Holocaust Remembrance Center, Jerusalem, Israel.

Grossman worked nights making prints that he freely distributed, only keeping the negatives. In August 1944, shortly before the final liquidation of the ghetto, Grossman hid his negatives in round tin cans. He was deported to a labor camp in Königs Wusterhausen Germany where he was imprisoned until April 16 1945. Ill and weakened, he perished during a forced death march, still wearing his camera on a sling inside his coat.[xvi] After liberation, Grossman’s sister found his negatives and sent them to Israel. However, most of them were lost during the War of Independence, when Egyptian troops captured the Nitzanim kibbutz. Fortunately, a friend succeeded in saving the Judenrat[xvii] archives that included some of Grossman’s photographs at the bottom of a well. Thus, Grossman’s legacy is based on the surviving photographs that he freely circulated, which are often not in ideal condition and difficult to authenticate and date as they were made and preserved in turbulent situations. The images in this essay are from the Łódź Ghetto collection of Mendel Grossman and his assistant Aryeh Ben Menachem at Yad Vashem: The World Holocaust Remembrance Center, Jerusalem, Israel.

Figure 3.14 Mendel Grossman. Feathers in Church, 1940—1944.

Yad Vashem: The World Holocaust Remembrance Center, Jerusalem, Israel.

Grossman’s loosely composed photographs chronicle the endless German-imposed deprivations that were thinly disguised in legalese, turning the word “Jew” into a profanity with two legs. Grossman’s works share qualities with the FSA social-realistic photographs depicting impoverished Southern sharecroppers made by Jewish Lithuanian immigrant Ben Shahn.[xviii] To unpretentiously chronicle everyday living in an economic system of bigotry and ignorance, Shahn at times used a Leica camera with a right-angle viewfinder, a device that permits a photographer to face in one direction while pointing the camera in another.[xix] Shahn’s spontaneous sketch-book style, in which the key subject(s) may not be in critical focus or are obscured by other pictorial elements, are indicative of his philosophy that content reins over aesthetics and/or technique, encouraging viewers to actively discover what is important to take away from his account. Shahn also understood the importance of photographing with humane resolve, once telling his FSA boss, Roy Stryker: “You’re not going to move anybody with this eroded soil—the effect this eroded soil has on a kid who looks starved, this is going to move people.”[xx]

Figure 3.15 Ben Shahn. Cotton Pickers, Pulaski County, Arkansas, 1935. Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

Grossman acted secretly and quickly and depended on open, snapshot-like compositions. They are not neat and tidy and contain classic snapshots “errors” such as off kilter framing, out of focus and/or poorly-lit subjects. Yet these unpretentious images are simultaneously highly accessible and highly uncomfortable as they carry a kismet subtext of raw violence and ask more questions than they answer.

Figure 3.16 Mendel Grossman. Hangings, 1940—1944.

Yad Vashem: The World Holocaust Remembrance Center, Jerusalem, Israel.

As a group, it is precisely Grossman’s rushed, impreciseness that makes one look outside of his photographic frame where we see an abyss: a world without Jews. In hindsight, Grossman’s ghetto photographs portray absence—not just the dead, but of a culture erased. The photographs confirm that the Jewish admission price for joining mainstream European society, submerging their identity by undergoing a de-Jewing process of hiding their Jewish beliefs and practices and/or converting to Christianity (more on this theme in the conclusion in next essay), was a failure since the group they wanted to belong to decided they were not human, but vermin –a swear word with two legs – pariah that had to be destroyed.[xxi]

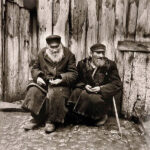

Figure 3.17 Mendel Grossman. Shmuel Grossman, 1940—1944. |

Figure 3.18 Mendel Grossman. Scavenging for Food and Fuel, 1940—1944. |

Figure 3.19 Mendel Grossman. Yakov (Yankush) Freitag, 1940—1944.

Yad Vashem: The World Holocaust Remembrance Center, Jerusalem, Israel.

Unlike the German’s staged and orderly documents, the simplicity and direct connection to reality is what gives Grossman’s works their authenticity and power to convey the gloom, grief, and suffering of his subjects, especially those of his immediate family. They impart a corporeal sense of anguish and vanishment, including his own family’s downward spiral towards oblivion, owing mainly to starvation and exhaustion. The camera is not neutral observer; therefore, it is important to know who took the photographs and understand their motivation.

The simplicity of Grossman’s photographs does what people expect photographs to do best: preserve moments in time as future records. Most people believe time is a straight arrow into the future. However, in Judaism, time is more like a spiral that allows the present and the past to simultaneously exist, so that the Jewish experience in Europe endures side-by-side with their travails in Egypt. Grossman’s cooperatively-made photographs demonstrate the collective Jewish will to endure and SAVE their vanishing world from extinction, and not end up like the Babylonians—relics in museum display cases.

Figure 3.20 Mendel Grossman. Father Dying, 1940—1944. |

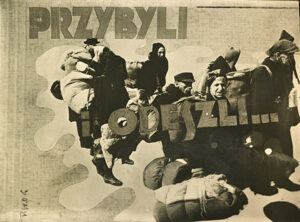

Figure 3.21 Aryeh Ben Menachem (Arie Princ). They Came and They Went Away, 1940—1944. |

These photographs had another surprising incarnation as collages that were part of an underground album produced by Jews connected with the statistics department.

The physical cutting, rearranging and gluing of photographs, plus the inclusion of text demonstrates their creative drive to tell a more complex story from multiple points of view. One wonders if they had seen any of the German artist John Heartfield’s anti-fascist photomontages? Heartfield was a pacifist who became number-five on the Gestapo’s Most Wanted List for the crime of using his “art as a weapon” to reveal the fascist lies and ludicrous conspiracy theories along with the collusion of the big industrialists.

Figure 3.22 John Heartfield. Adolf the Superman: Swallows Gold and Spouts Rubbish, AIZ (Arbeiter-Illustrierte Zeitung) 11. no. 29, July 17, 1932. Rotogravure. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, CA.

The cultural/social underpinning of these photographs remind us that humans have not been able to overcome their nationalism and tribalism, which fuels hate and violence. Conversely, accurate historic knowledge at least gives people a rational foundation for making more intelligent, informed, and humane decisions. The challenge remains: How can humankind reckon with its violent and often unjust history and what role can photography play in confronting and learning from such failures?

To Be Continued…

Afterward

This ongoing project is flexible and subject to revision as it progresses.

Feedback and suggestions are welcome.

Research assistance by Ruby Merritt

Special thanks to Lisa Murray-Roselli for her copy-editing expertise.

This theme is supported by the following organizations and individuals:

VASA, Vienna, Austria: Roberto Muffoletto, Director

CEPA Gallery, Buffalo, NY USA: Véronique Côté, Executive Director & Chief Curator

Galicia Jewish Museum, Kraków, Poland: Tomasz Strug, Deputy Director and Chief Curator

Holocaust Resource Center of Buffalo, Buffalo, NY USA: Elizabeth Schram, Director

Jewish Community Center of Greater Buffalo, Buffalo, NY USA: Katie Wzontek, Cultural Arts Director

Endnotes:

[i] Roland Barthes, The Grain of the Voice, (London: Jonathan Cape, 1985), p.356.

[ii] The English word ghetto is derived from the Venetian Ghetto, an area of Venice in which Jews were forced to live by the government of the Venetian Republic in 1516.

[iii] Who is a Jew? The Nuremberg Race Laws of 1935 institutionalized many of the Nazi racial theories and provided the legal framework for the systematic persecution of Jews in Germany. The Nuremberg Race Laws did not identify a “Jew” as someone with particular religious convictions, but instead as someone with three or more grandparents born into the Jewish religious community. Grandparents born into a Jewish religious community were considered “racially” Jewish. Their “racial” status passed to their children and grandchildren. Even people with Jewish grandparents who had converted to Christianity could be defined as Jews. Under the law, German Jews were not citizens but “subjects” of the state who among other of hundreds of endless restrictions were forbidden from marrying Aryans. The net effect is whether a Jew wants to be identified as a Jew is of no consequence because being a Jew is “in the blood,”making Judaism a separate race. It also infers group responsibility in that the actions of an individual Jew are applied to all Jews. See: https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/nuremberg-laws

[iv] See: Max Kozloff, New York: Capital of Photography, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002) and Michael Berkowitz, Jews and Photography in Britain, (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2015).

[v] See: Grodzka Gate – NN Theatre. “In the Footsteps of Local Photographers” https://shtetlroutes.eu/en/in-the-footsteps-of-local-photographers and YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, “People of a Thousand Towns” The Online Catalog of Photographs of Jewish Life in Prewar Eastern Europe @ http://yivo1000towns.cjh.org/

[vi] The largest Jewish communities were in Poland, with about 3,000,000 Jews (9.5%); the European part of the Soviet Union, with 2,525,000 (3.4%); and Romania, with 756,000 (4.2%). The Jewish population in the three Baltic states totaled 255,000: 95,600 in Latvia, 155,000 in Lithuania, and 4,560 in Estonia. Here, Jews comprised 4.9%, 7.6%, and 0.4% of each country’s population, respectively, and 5% of the region’s total population. See: https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/jewish-population-of-europe-in-1933-population-data-by-country

[vii] Herbert Mitgang, “Testament to a Lost People.” The New York Times Magazine, October 2, 1983, p. 47.

[viii] UCSB Arts & Lectures (2000). Work of photographer Roman Vishniac remembered in special illustrated program at UCSB. See: https://web.archive.org/web/20041120013228/http://www.artsandlectures.ucsb.edu/archive/1999-2000/pr/vishniac.htm

[ix] Indepth Arts News: “Vishniac Photographs Breathe Life into Memories of Children from a Vanished World” January 2001. See: www.absolutearts.com/artsnews/2001/02/01/28027.html

[x] See: Barbie Zelizer, Remembering to Forget, (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1998), 39.

[xi] Photographs of the Farm Security Administration – Office of War Information Photograph Collection at: www.loc.gov/collections/fsa-owi-black-and-white-negatives/about-this-collection/

[xii] Michael Zhand, “That Iconic ‘Migrant Mother’ Photo Was ‘Photoshopped,’” https://petapixel.com/2018/11/30/that-iconic-migrant-mother-photo-was-photoshopped/?mc_cid=83f45426b5&mc_eid=158a2b7ee5

[xiii] Before the Holocaust Jews made up one third of Łódź’s population, Poland’s third latest city. Intense, sanctioned discrimination, persecution, plundering, and murder of the Jewish population began immediately after the Nazi invasion in September 1939.

[xiv] See: Matt Lebovic, “80 years ago this month, Nazis invented ‘industrial murder’ at quiet Chelmno,” The Times of Israel, December 13, 2021, www.timesofisrael.com/80-years-ago-this-month-nazis-invented-industrial-murder-at-quiet-chelmno/?utm_source=The+Daily+Edition&utm_campaign=daily-edition-2021-12-13&utm_medium=email

[xv] “Mendel Grossman: The Łódź Ghetto Photographer”www.holocaustresearchproject.org/ghettos/grossman.html

[xvi] Dawid Sierakowiak; Alan Adelson, ed.; Kamil Turowski, (translator), The Diary of Dawid Sierakowiak: Five Notebooks from the Łódź Ghetto, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), 269–270.

[xvii] During World War II, the Germans established Jewish councils, commonly called Judenraete. These Jewish municipal administrations were required to implement Nazi orders and regulations. Council members attempted to perform an impossible balancing act of trying to provide basic community services while deciding whether to comply or refuse to comply with German demands, such as providing names of Jews for deportation. These Jewish councils remain a highly controversial subject. See: https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/jewish-councils-judenraete

[xviii] Shahn had shared a Manhattan studio with the photographer Walker Evans, who gave him rudimentary photography lessons.

[xix] T. J. Maloney, ed., U.S. Camera 1940 (New York: Random House, 1939), 197.

[xx] Richard Doud, interview with Shahn conducted by April 14, 1964; quoted in F. Jack Hurley, Portrait of a Decade: Roy Stryker and the Development of Documentary Photography in the Thirties (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1972), 50.

[xxi] This is related to “Racial Passing” in which a person classified as a member of a racial group is accepted or perceived as a member of another, usually by suppressing their actual identity to avoid discrimination and enjoy the benefits of belonging to the mainstream culture. Even now Jews decide whether or not to hide or celebrate their particularities: Do you wear a Star of David or put a mezuza on the door or do you prefer that people to know much about you?

[xxii] www.facinghistory.org/resource-library/text/diary-entry-hunger-d-ghetto-march-11-1942 from Alexandra Zapruder, ed., Salvaged Pages: Young Writers’ Diaries of the Holocaust, 2nd edition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015) 137–138.

Image References:

Figure 3.0

3.0 Mendel Grossman Archive Tattooed Child, 1940—1944.

Yad Vashem: The World Holocaust Remembrance Center, Jerusalem, Israel.

Caption: The forced tattoos are one of the most recognizable symbols of the Holocaust and its deadliest camp. Only prisoners at Auschwitz and its sub-camps, Birkenau and Monowitz, were tattooed. The tattooing started in autumn 1941 and by the spring of 1943, all prisoners were tattooed. It was segment of a chain of dehumanizing and humiliating actions that were inflicted upon arrival to the camp. The prisoners understood they were losing their names and officially they were now numbers. See: “Tattoos and Numbers: The System of Identifying Prisoners at Auschwitz,” https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/tattoos-and-numbers-the-system-of-identifying-prisoners-at-auschwitz

Figure 3.1

Figure 3.1 Roman Vishniac. Old Man, Carpathian Ruthenia, circa 1935–1939. © Mara Vishniac Kohn, courtesy International Center for Photography, New York.

Figure 3.2

Figure 3.2 Roman Vishniac. Granddaughter and Grandfather, Warsaw, circa 1935–1939. © Mara Vishniac Kohn, courtesy International Center for Photography, New York.

Figure 3.3

Figure 3.3 Roman Vishniac. Antisemitic Boycotts Changed Peddlers Into Beggars, Łódź, Lublin, or Warsaw, circa 1935-1938. © Mara Vishniac Kohn, courtesy International Center of Photography, New York.

Figure 3.4

Figure 3.4 Roman Vishniac. Chaim Simcha Mechlowitz, circa 1935–1938 in Vysni Apsa, Carpathian Ruthen. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC.

Caption: Chaim Simcha Mechlowitz was a farmer and tanner who was deported to Auschwitz after Germany occupied Hungary in March 1944. He did not survive. Carpathian is now part of Ukraine. Vishniac’s caption did not name him but, his granddaughter recognized him when she saw this portrait on exhibition at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Figure 3.5

Figure 3.5 Roman Vishniac. Nettie Stub (age 11 from Hanover, Germany, in the Polish detention camp Zbaszyn), November 1938. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC.

Caption: After Vishniac photographed Stub in Zbaszyn, the Red Cross evacuated her to Sweden. Her parents and two siblings, who were not able to escape Poland, perished. An older brother, who survived being imprisoned in Buchenwald, tracked Nettie down after the war and they immigrated to New York in 1945.

Figure 3.6

Figure 3.6 Dorothea Lange. Migrant Mother – Florence Owens Thompson (unretouched), 1936. Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

Caption: When Lange made this photograph, Thompson was holding the log that was propping up her temporary tent. In 1939, Lange instructed her assistant to retouch the image and remove Thompson’s thumb because she considered it to be a conspicuous compositional imperfection. Thus, the iconic version includes a blurry spot where Thompson’s thumb once was while her left index finger remains.

Figure 3.7

Figure 3.7 Roman Vishniac. Talmudic Scholar, Kraków, circa 1935–1939. © Mara Vishniac Kohn, courtesy International Center for Photography, New York.

Caption: The first synagogue in Poland was built in Kraków in 1356, where Jews held prominent positions. However, the Christians became jealous and in 1392, they banned the sale of property to Jews. Pogroms became a regular occurrence in the fifteenth century and in 1494, King Olbracht expelled the Jews from Kraków. When Germany invaded Poland in 1939, 65,000 Jews were living in Kraków. In December of that year, synagogues were burned, and in 1940, the Germans expelled half the Jewish population. From the summer of 1942 through the spring of 1943, Jews were either shot or sent to the Plaszow labor camp, or the Belzec or Auschwitz extermination camps.

Figure 3.8

Figure 3.8 Roman Vishniac. Cheder Boy, Carpathian Ruthenia, circa 1935–1939. © Mara Vishniac Kohn, courtesy International Center for Photography, New York.

Caption: A cheder is a Jewish elementary school where Hebrew and religious classes are conducted. Carpathian Ruthenia included some of the poorest and most pious Jewish communities in Eastern Europe. Before World War II, more than 100,000 Jews lived in this area. In the spring of 1944, most of the Carpathian Jews were deported to Auschwitz and murdered. Carpathian is now part of Ukraine.

Figure 3.9

Figure 3.9 Aryeh Ben Menachem. Grossman at the Rubble of Łódź Synagogue, Wolborska Street, circa 1940. Yad Vashem: The World Holocaust Remembrance Center, Jerusalem, Israel.

Caption: The Great Synagogue of Łódź was built in 1881. The synagogue was blown up and burned to the ground by the Germans on the night of November 14, 1939, along with its Torah scrolls (one was saved from the rubble). It was dismantled in 1940. Today it is parking lot.

Figure 3.10

Figure 3.10 Mendel Grossman. Corpse of a Jewish Man Murdered during Deportation, 1942. Yad Vashem: The World Holocaust Remembrance Center, Jerusalem, Israel.

Caption: Grossman photographed deportees from nearby Zdunska Wola who had died anonymously from suffocation in a packed train. His photographs revealed the numbers on their chests, which later allowed families to identify their numbered graves. What the Europeans called The Jewish Question was not a Jewish problem, but one for the rest of the world that denied their humanity.

Figure 3.11

Figure 3.11 Mendel Grossman. Saying Goodbye, 1942. Yad Vashem: The World Holocaust Remembrance Center, Jerusalem, Israel.

Caption: Saying goodbye to children held at the Łódź ghetto prison before they were deported to Chelmno and gassed.[i] Cruelty was the point and people did it willingly. Nazis considered Jews flies and thought nothing of pulling off their wings. See: Matt Lebovic, “80 years ago this month, Nazis invented ‘industrial murder’ at quiet Chelmno,” The Times of Israel, December 13, 2021, www.timesofisrael.com/80-years-ago-this-month-nazis-invented-industrial-murder-at-quiet-chelmno/?utm_source=The+Daily+Edition&utm_campaign=daily-edition-2021-12-13&utm_medium=email

Figure 3.12

Figure 3.12 Mendel Grossman. Scheisskommandos (shit commando)1940—1944. Yad Vashem. The World Holocaust Remembrance Center, Jerusalem, Israel.

Caption: A family lugging a wagon filled with excrement through a ghetto street. Forced to work in the most unsanitary conditions, they would likely be exposed to typhus, an infectious disease characterized by a purple rash, headaches, fever, and delirium. It is commonly transmitted by lice, mites (chiggers), rat fleas, and ticks. Historically typhus caused high mortality rates during wars and famines.

Figure 3.13

Figure 3.13 Mendel Grossman Collection. Scheisskommandos, 1940—1944. Yad Vashem. The World Holocaust Remembrance Center, Jerusalem, Israel.

Figure 3.14

Figure 3.14 Mendel Grossman. Feathers in Church, 1940—1944. Yad Vashem: The World Holocaust Remembrance Center, Jerusalem, Israel.

Caption: Grossman photographed the inside of the Church of the Virgin Mary in the ghetto, whose altar and saints and huge organ were completely covered with feathers that had been ripped from the pillows and featherbeds stolen from the Jews sent to their deaths. Slashed open by Jewish slave laborers, the looted feathers were then cleaned, sorted, packed, and shipped to Germany.

Figure 3.15

Figure 3.15 Ben Shahn. Cotton Pickers, Pulaski County, Arkansas, 1935. Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

Caption: While hiding in a room overlooking Bazarny Square, Grossman made this long-distance photograph, of an execution of a Jew from Vienna who had been arrested outside of the ghetto. Afterwards, he photographed this multiple hanging of Jews in close proximity, which were regularly carried out for anything that displeased the Germans.

Figure 3.16

Figure 3.16 Mendel Grossman. Hangings, 1940—1944. Yad Vashem: The World Holocaust Remembrance Center, Jerusalem, Israel.

Caption: After taking a long-distance photo while hiding in a room overlooking Bazarny Square, of an execution of a Jew from Vienna, who had been arrested outside of the ghetto, Mendel was able to photograph this hanging of Jews in close proximity.

Figure 3.17

Figure 3.17 Mendel Grossman. Shmuel Grossman, 1940—1944. Holocaust Research Project.

Figure 3.18

Figure 3.18 Mendel Grossman Scavenging for Food and Fuel, 1940—1944. Holocaust Research Project.

Caption: Part of an entry from the diary of an anonymous girl from March 11, 1942, in which she describes the hunger and starvation she faced in the Łódź ghetto: “This ration is much worse than the previous one. Terrible hunger is awaiting us again. I got the vegetable ration right away. There is only vinegar and ice in the beets. There is no food, we are going to starve to death. All my teeth ache and I am very hungry. My left leg is frostbitten. I ate almost all the honey. What have I done? I’m so selfish. What are they going to put on their bread now, what will they say? Mom, I’m unworthy of you. You work so hard. Besides working in the workshop, she also moonlights by working for a woman who sells clothes in the street. My mom looks awful, like a shadow. She works very hard. When I wake up at twelve or one o’clock at night, I see her exhaustedly struggling to keep working on the sewing machine. And she gets up at six in the morning. I must have a heart of stone. I’m ruthless. I eat everything I can lay my hands on.” See: www.facinghistory.

Figure 3.19

Figure 3.19 Mendel Grossman. Yakov (Yankush) Freitag, 1940—1944. Yad Vashem: The World Holocaust Remembrance Center, Jerusalem, Israel.

Caption: During the four years of the Łódź ghetto’s existence, Grossman lived with his parents, two sisters, brother-in-law, and young nephew in a crowded apartment. Through his camera, Grossman watched his family’s cascading deterioration, which was typical of other ghetto families. Grossman’s brother-in-law was the first to die, dropping dead of cold, exhaustion, and starvation in the same raggedy clothes and wooden clogs in which Grossman had earlier photographed him. Here Grossman photographed his sister’s little son sucking on a frozen carrot. It was characteristic of the dreadful food available in the Łódź ghetto, making a painful archetypical image of the doomed Jewish ghetto children.

Figure 3.20

Figure 3.20 Mendel Grossman. Father Dying, 1940—1944. Yad Vashem: The World Holocaust Remembrance Center, Jerusalem, Israel.

Caption: Grossman’s emaciated father, wrapped in a tallit, in bed under blankets due to the brutal cold, died as Grossman stood at his deathbed with his camera.

Figure 3.21

Figure 3.21 Aryeh Ben Menachem (Arie Princ). They Came and They Went Away, 1940—1944. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC.

Caption: This collage was created by Arie Princ (Aryeh Ben Menachem) using photographs by Mendel Grossman and documents from the Łódź ghetto. The text reads: “Przybyli i odeszli…” (They came and they went away). The collage was published during World War II by the underground organization PWOK, the Aid for Prisoners of Concentration Camps.

Figure 3.22

Figure 3.22 John Heartfield. Adolf the Superman: Swallows Gold and Spouts Rubbish, AIZ (Arbeiter-Illustrierte Zeitung) 11. no. 29, July 17, 1932. Rotogravure. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, CA.

Caption: John Heartfield’s photomontage combines fantasy and reality to depict Adolf Hitler as a gluttonous swallower of big industrial money who spouts meaningless words. Monetary exchange is made physically real and repulsive as it is presented in the abstract form of a digestive body, which symbolizes a system of ingestion and suggested regurgitation. This montage was published in the AIZ, where it was preceded by an article examining the incongruity between the Nazis anti-capitalist rhetoric and their pro-capitalistic practices.