Return to Issue 3 Table of Contents

(This is the second part of the complete text of a lecture delivered by A. D. Coleman on November 8, 2011 at Hotshoe Gallery, London, co-sponsored by Hotshoe International, Viewfinder Photography Gallery, and the VASA Project. Part One appeared in the previous issue of the VJIC. ― Editor)

A. D. Coleman (l) and Roberto Muffoletto (r), Hotshoe Gallery, London, November 8, 2011. Photo © copyright 2011 by Anna Lung.

Let me return to considering the state of the discourse. Due to an unfortunate combination of circumstances, I parted company with the Village Voice in 1973 and the New York Times in 1974, published in assorted comparatively small-circulation or targeted periodicals for the next 14 years, and didn’t establish a platform at another general-audience publication until I commenced my column in the New York Observer in 1988.

So, as a working critic, I was sidelined during much of the photo boom that brought the medium to center stage in the art world and the wider culture. Still, I felt heartened to watch photography start to get some of the attention it deserved and photographers ― including some who’d paid a lot of dues ― start to get some respect.

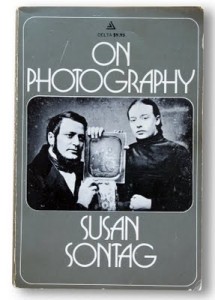

Susan Sontag, “On Photography,” 1977, cover.

But then two things happened unexpectedly. First, in 1977 Susan Sontag published the one book on the medium that we can now expect a culturally literate person to have read. She titled it On Photography, though she subsequently confessed that “[On Photography] is not about photography! [Emphasis in the original.] . . . Now you’ve got me. I said it, and I didn’t mean to say it. It’s not about photography, it’s about the consumer society, it’s about advanced industrial society . . . [and] about photography as the exemplary activity of this society. I don’t want to say it’s not about photography, but it’s true . . . I’m not a photography critic. I don’t know how to be one.”1

Well, silly me ― and perhaps silly us ― for taking her book’s title at face value, instead of sussing out that she’d simply chosen photography as a convenient whipping boy. Among the things that disturbed me about Sontag’s treatise were its “case closed” tone, which discouraged its readers from inquiring further into the medium’s field of ideas by suggesting that it had none, and the fact that nowhere in it (indeed, nowhere in any of her subsequent writings on the medium) does Sontag pay close, careful attention to even a single photograph, verifying her assertion that she didn’t know how to be a photography critic.

A quarter-century later, in her book Regarding the Pain of Others (2002), Sontag recanted many of her positions on the grounds that they were “now fast approaching the status of platitudes” ― as if they hadn’t been such when first uttered. But the impact of the first book has far exceeded any counterbalancing effect of the much less influential follow-up. Certainly no one who has used her original aphorisms and aperçus as substantiation for their own positions has felt any need to revise their stands drastically because Sontag did so with hers.

Sontag’s book was written in accessible language; even the passages plagiarized from Roland Barthes came from his newspaper columns, not his denser treatises. But On Photography served in part to popularize the set of ideas concerning photography and its relation to culture that was coming to be known as postmodernism. The usefulness of some of those ideas notwithstanding, the advent of postmodernist criticism precipitated a breathtakingly rapid descent into a highly jargonized discourse with a patently gatekeeping subtext. Most of those producing it showed no interest in mainstreaming their theories via general-audience publications;2 they published in (and often founded for that purpose) small-circulation journals like October and Afterimage.

A few advocates for that movement, like Andy Grundberg at the New York Times and Ingrid Sischy at the New Yorker, achieved a more penetrable style in which to propound postmodern notions. But their writing made it clear that one purpose of this approach was to valorize a certain defined set of practitioners and, to use one of their favorite locutions, “discredit” others (Minor White, W. Eugene Smith, Sebastião Salgado among the “discredited”). These elevations and dismissals were based not on the power of the photographers’ work but on assessment of the correctness of their politics. All of this reminiscent, if you know your music history, of the Stalinist Ewan McColl organizing the members of the UK’s folk-music clubs to disrupt Bob Dylan’s pioneering rock & roll concerts during his 1966 tour.

Whatever our respective relationships to postmodernism, I’d hope we could agree that in practice postmodern theory does not encourage close scrutiny of individual images as such, nor concern itself with their facture or the physical characteristics of them as crafted objects. One can read the entirety of the critical literature on Cindy Sherman, for example, without encountering much in the way of detailed description of any of her images or prints. To whatever extent Sontag and the postmodern critics addressing photography from the 1970s on prompted people to think about photography and photographers in the abstract, they didn’t do much to make them feel it might be important to “sit and look at the pictures.” Nor to make them feel that engaging critically with photography could be done by the average citizen, in everyday language, without benefit of clergy.

•

The decade following the publication of Sontag’s book saw an enormous investment in projects and activities devoted to the sesquicentennial of photography, the designated 150th anniversary of the medium’s public birth. New museums of photography, new departments of photography in art museums, new photo festivals in dozens of countries; new histories of photography and other monographs in dozens of languages ― these and more made a wealth of images and information about them available to a rapidly widening audience for the medium.

We missed that boat. For a year or more the world regularly turned its eyes to the medium. We did not have a cohort of critics ready, willing, and able to take advantage of that teaching moment and convert it to a permanent, multi-levelled, polyvocal public debate about photography, its practitioners, their images, and the many issues relating to all those. With all the hooplah attendant on the sesquicentennial, you’d have thought that by the end of 1989 every major newspaper and general-audience magazine, and many minor ones, would have a knowledgeable writer on photography on call, if not on staff, and contributing regularly. That never happened, perhaps because so many of my colleagues were busying themselves distinguishing the signifier from the signified, a distinction that, incomprehensibly, has never gripped the public imagination.

By dint of perseverance and good fortune, in mid-1988 I’d managed to establish myself at the New York Observer, a weekly newspaper, as their official photography critic, producing a weekly column. By then art magazines worldwide had opened themselves up to coverage of photography, and a whole slew of “little” photo magazines had sprung up. I multipurposed and self-syndicated that Observer material, and more, to publications across North America, in Europe, and in the U.K., for close to a decade. Some I converted to broadcasts for National Public Radio. It felt as if, in tandem with my colleagues, we were all right on the cusp of something huge, the field of photography simultaneously consolidating and expanding.

Then the tsunami of the World Wide Web hit, as previously mentioned, rapidly changing the publishing industry in ways that certainly didn’t benefit writers as professional content providers. And the web represents an even larger, epochal change: the cultural shift from analog to digital information at every level ― production, storage, retrieval, transmission. Suddenly it became possible to create an image, or a text, without having to create an object ― the dematerialization of communication.

As a result, the medium of photography itself has morphed into something so new and different that we begin to call it by other, provisional names. Post-secondary former departments of photography scramble to rename themselves: digital imaging, multimedia, media arts. Museums of photography, photo festivals, and photography magazines face the same challenge. And so, certainly, do those few of us self-identified as photography critics. If the terms photographer and photography now inch toward the archaic, photo criticism as a descriptor can’t lag far behind.

I’ve deliberately defined my territory widely, from the start. I continue to believe, as I always have, that there’s a value to having someone grounded in the history and evolution of lens-based imagery addressing the broadest spectrum of work related to that medium, from classic 19th-century photography through photo-based art to photorealist painting to holography. Increasingly, however, I see work at photo festivals, in photo galleries and museums, at the websites of artists self-defined as photographers, that includes kinetic as well as still imagery, incorporates sound or animation or computer graphics, presents itself in installation format. At what point does the rubric “photography” cease to function as an accurate way of identifying such projects, and when does it become unproductive, indeed inaccurate, to call someone who writes about such works a photography critic?

Were I setting out today on an updated version of the enterprise I initiated in 1968, even one in which critical attention to 19th- and 20th-century photography played a central role, I wouldn’t present myself to editors as a photography critic, out of concern that they’d find that not just overly narrowcast but even esoteric. I don’t know what I’d substitute, but that designation has now outlived its usefulness, though a few of us who mined that vein when it ran rich may end up stuck with it for life.

•

Mind you, though I’m technoskeptical I’m not technophobic. I’ve written about electronic communication and the emergence of digital forms since the late 1960s. As a professional writer, I’ve worked on a computer since the late 1980s. I started publishing my first website, and my first blog (though we didn’t have that term then) in 1995, making me an early adapter of the World Wide Web. Nowadays I publish and edit four sites. I also write reviews of computer software and hardware for Mac Edition Radio, a website. So I’m comfortable in the digital environment.

And I want to make it clear that I’m not mourning the passing of print per se as the vehicle for a critical dialogue about photography. Conceivably that dialogue could take place in cyberspace. To date, and to my surprise, I’m alone among my colleagues in establishing a substantial presence on the web via a site of my own. And while some photography magazines have gone online, such as Viewfinder and Hotshoe, they emphasize presentation of photographers’ projects rather than critical discourse.

Yet even if dozens of my colleagues start blogging and one or more online journals devoted to photography criticism emerge, as I hope they will, that won’t have much more impact on the broader culture than would the publication of several more equivalent specialized print journals. The effect won’t be the same as it would be if, say, the International Herald Tribune and Newsweek added photo critics to their rosters for the first time, and the New York Times returned such a designated hitter to its staff ― even if those publications were to terminate their print editions and become entirely web-based.

Because that coverage, in such forums, in print or online, signals that a medium has achieved a level of cultural gravitas. Recall, if you’re old enough, the pivotal moments when criticism of jazz and then rock & roll moved beyond such magazines as Down Beat, Metronome, and Crawdaddy in the States, or Melody Maker here in the U.K., and started showing up in the pages of the London Times, and you’ll know what I mean.

•

Whatever the condition of the discipline of photography criticism, the still photograph remains much more than an obsolescing historical artifact. Over the past several decades we’ve had a number of teaching moments, occasions on which commentary from prominent, articulate critics knowledgeable about the medium should have formed part of the public debate over situations involving the medium:

- the so-called “culture wars,” of course, in which much of the attack from the right centered around controversial photographs;

- the ongoing U.S.-led “coalition of the willing” war with Iraq, which began in 2003, premised itself in part on energetic misinterpretation of aerial photographs, ostensibly showing manufacturing sites for weapons of mass destruction that did not in fact exist;

- the Abu Ghraib scandal of 2006 that discredited the U.S. in much of the Middle East and elsewhere resulted from the release of snapshots of torture of prisoners, images made by unidentified U.S. military personnel;

- and the resignation in 2011 of Democratic U.S. Congressman Anthony Weiner over the “Weinergate” photos started with the disclosure of self-portraits he’d used in “sexting” a 21-year-old woman via the social media website Twitter, images he suggested had been “doctored” before ‘fessing up and leaving office.

These particular instances highlight the fact that the still photograph has not lost its potency as a cultural artifact. To the contrary, photographs made and presented within the contexts of vernacular photography, news photography, evidentiary photography, and contemporary art activity have provoked extraordinary response in our time. Meanwhile, digital imaging has unleashed a flood of altered still images, as well as an upsurge in claims that verifiably unaltered images have somehow been falsified.

We can’t afford a citizenry unsophisticated in its relation to such images and unequipped to question and challenge manipulative public presentations thereof. Such a discourse requires exemplars and guides, roles in which dedicated critics serve the public. But they can only provide that service when they speak from platforms that make them publicly visible. Such platforms, never plentiful, have dwindled in number and seem likely to disappear altogether.

•

A. D. Coleman (l) and Roberto Muffoletto (r), Hotshoe Gallery, London, November 8, 2011. Photo © copyright 2011 by Anna Lung.

Allow me to sum up what I’m proposing as the symptoms and causes of the demise of photography criticism as a substantial public discourse.

- Unlike criticism of most of the other creative media ― literature, music, film, theater, dance, the visual arts ― photo criticism never established more than a tenuous toehold in widely distributed general-audience publications, such as newspapers and magazines devoted to coverage of cultural issues. Thus it never became a mainstream form of criticism, remaining a peripheral or minor one at best.

- The limited opportunity to do such work for adequate compensation made the discipline of photo criticism less than attractive to potential practitioners of this craft. This enabled only a few people to pursue it vocationally; most engage with it avocationally.

- The lack of any financial support for photo criticism (in the form of advertising) from the institutions and industries that sponsor the public presentation of photography ― museums, galleries, book publishers ― made the inclusion of photo criticism in such periodicals optional and thus dispensable, from a financial point of view. The current international financial crisis ensures that this situation will only get worse.

- The absence of a responsive audience for photo criticism ― an audience ready, willing, and able to interact energetically and publicly with photo critics via letters to the editor ― not only delimits the dialogue to infrequent public exchanges between critics but means that editors and publishers remain unaware of the existence of any readership for any photo criticism that they put into print.

- Postmodern theory has dominated critical writing about photography since the late 1970s. The writing style of many critics of the postmodernist tendency is off-putting to the average reader (and thus to the editors of large-circulation periodicals). Most such writers thus restrict their writing to specialized, small-circulation journals and their audiences to the readership thereof.

- Concentration by many postmodernist critics on a small roster of photographers and artists using photography ― Jeff Wall, the Bechers and their students, Barbara Kruger, Richard Prince, Cindy Sherman, Andres Serrano, Alfredo Jaar, Laurie Simmons, Robert Mapplethorpe ― has in fact ensured the existence of a “continuum of understanding, early commenced” that constitutes the early phase of a critical tradition for their work. But there’s a much wider range of significant work, past and present, that has received insufficient critical attention, and that gap widens instead of shrinking.

- An opportunity to mainstream photo criticism presented itself in the 1980s, in connection with the energy and activity surrounding the upcoming sesquicentennial of photography in 1989. While that period resulted in the establishment of new photography museums and festivals, other new photo-related institutions and organizations, new magazines of photography, and other ventures, it did not lead to an increased presence of photo critics in the mainstream media ― due in part to the shortage of critics able to communicate effectively in such forums, and interested in so doing.

- The crisis of the print publishing industry generated by the advent of digital formats and the World Wide Web has led to the drastic cutting down of editorial space available for perceived “boutique” content such as photo criticism.

- The replacement of critics specialized in one or another of the arts with generalist “cultural journalists” has radically reduced the opportunities for knowledgeable photo critics to establish platforms for their work in large-circulation general-audience periodicals, whether in print or online.

- The shortened attention span of the contemporary audience is not compatible with the standard form for critical writing: the substantial, carefully argued prose essay.

- The transformation of the medium of photography itself, the transition from analog to digital for most of the primary forms of vernacular and quotidian photography and even many of its specialized uses, has redefined the medium to such an extent that defining the activity under consideration as photography criticism may not effectively outline the territory such a commentator would explore.

For all those reasons, then, I think the heyday of photography criticism has passed. I don’t mean to suggest that no one will write passionately, critically, and well about photography ever again, and I can state as a certainty that numerous others have done so to date. But as a variant of the cultural function sometimes called the public intellectual, the photography critic per se made it out of the minor leagues only briefly, and photo criticism as the form in which such an individual would cast his or work has rarely escaped its microbrew status. I don’t say this to castigate anyone else, nor to fault myself. Though I think it might have gone differently, I can’t prove that.

So yes, Kyle, I’m dinosaur bones ― and Andy Grundberg, Vicki Goldberg, Anthony Bannon, Vince Aletti, and a small bunch of others along with me. Hope springing eternal, as it tends to do, I’ll close by saying that perhaps time will convert us into a fossil fuel that can drive the engine of some future ongoing high-profile international public debate over lens-derived imagery of all kinds and their implications, facilitated by informed provocateurs. I don’t care whether they call themselves photo critics, or define their work as photo criticism.

Critical writing about photography is, in any case, a subset of critical writing in general, which in turn forms a category (though not often enough acknowledged as such) of literature. And I feel toward my little corner of that territory as Jean Rhys felt about hers: “All of writing is a huge lake. There are great rivers that feed the lake, like Tolstoy and Dostoevsky. And there are trickles like Jean Rhys. All that matters is feeding the lake. I don’t matter. The lake matters. You must keep feeding the lake.”

Return to Issue 3 Table of Contents

(You are invited to add to the conversation below.)

References

- These statements appear in Victor Bockris’s interview, “Susan Sontag: The Dark Lady of Pop Philosophy,” High Times, March 1978, p. 36. ↩

- For an unintentionally hilarious exemplification of the problems involved in translating pomo jargon into comprehensible English, see Richard Appignanesi and Chris Garratt’s deliriously impenetrable Postmodernism for Beginners (Cambridge: Icon Books, 1995). ↩