Return to Issue 2 Table of Contents

(This is the first part of the complete text of a lecture delivered by A. D. Coleman on November 8, 2011 at Hotshoe Gallery, London, co-sponsored by Hotshoe International, Viewfinder Photography Gallery, and the VASA Project. Part Two will appear in the next issue of the VJIC. ― Editor)

As someone who believes in the social value of the public shaming of miscreants, I find the web useful as a virtual substitute for the physical pillory. This past summer, in a pair of posts at my blog, Photocritic International, I identified and took to task a photographer who’d stolen an essay of mine from its licensed appearance at another website and posted it without permission or notification at his own blog. In early August, in response to these posts, one Kyle Newberry wrote ― not in a public comment at my blog, but in a private email to me ― “You’re dinosaur bones”; just those three words, not even a period.

I realize that this is what passes for thoughtful opinionation, nuanced argument, and scathing rebuttal amongst the cohort I think of as Generation Tweetie ― GenTweet for short. (Indeed, by the emerging standards of brevity in communication Newberry probably qualifies as verbose.) Easy enough to dismiss, of course ― my initial inclination. To quote Leonard Cohen, who, during his 2008 London concert, was quoting his 102-year-old zen teacher, “Excuse me for not dying.”1

But then I asked myself, suppose he’s right?

As it happens, I’ve pondered that question on my own in recent years, intermittently. This past spring I got interviewed at length for two different projects in progress: one organized by Carol McCusker on the “photo boom” that began in the late 1960s, and another on Garry Winogrand, organized by Leo Rubinfien and Susan Kismaric. These recorded dialogues took me into a reflective mode, reconsidering with hindsight my particular project as a critic of photography and the roles played by those I consider my colleagues in that discipline from the late ’60s on: Ben Lifson, Shelley Rice, Andy Grundberg, Vicki Goldberg, Carol Squiers, Charles Hagen, Vince Aletti, and then more recently David Levi-Strauss, Geoff Dyer, and some others.

And in both those conversations, which took place months prior to Newberry’s dorky email, I came to the same conclusion: I’m dinosaur bones. I even used the word dinosaur to refer to myself at least once in those conversations, as I recall. And I went further, suggesting that the very discipline I practice, photo criticism, had become Jurassic as well.

The question, then, echoes that which Yahweh poses to Ezekiel in the Old Testament: “Son of man, can these bones live?” Ezekiel, I remind you, answers, “O Sovereign Lord, you alone know.”2 You can count on “God knows” as a safe answer to just about any question. But, with no hubristic intent, let me voice what Ezekiel was likely thinking in his situation, and what I think in mine: I doubt it very much.

No, I’m not planning to shuffle off into the gloaming to lay myself down in some bog for eventual resurrection, perhaps as some latter-day Piltdown Man my detractors might anticipate, skull of a chimp and jawbone of an ass. My own project’s not nearly done, though I accept the possibility that it may get interrupted. Nor do I propose that writing about photography by others will cease. But a certain kind of writing about photography in certain kinds of forums, that which I and some others have practiced over the past four decades plus, has become obsolescent. This talk constitutes a vote of no confidence in the possibility of its revival any time soon.

Let me explain, first, what I mean by my own praxis and that of some of my peers, and then describe the situation that enabled it versus the situation we find ourselves in today.

•

The medium in which I work is ratiocinative prose. My preferred form is the prose essay, my preferred length between 1200 and 5000 words. I’ve published over 2000 such essays since 1967. As a professional writer I’ve defined myself from the outset through the present as a photography critic. Not, to use variants of the trendy locutions, an art critic using photography or a photo-based art critic. Just a photography critic, though according to others some of my writing qualifies me as a historian, some as a theorist, and the broader field I’m in has become known generically as cultural journalism.

What does a working photography critic do? Based on my engagement as a reader with criticism of literature, jazz, rock, and some other arts, the working critic develops an awareness of the particular medium’s full field of ideas, as articulated by performers, other critics, historians, and theorists; evolves positions in relation thereto; and engages with that field of ideas by addressing a reasonable cross-section of past and current work in the medium.

At least that’s how I’ve always understood it. How does that manifest itself in practice ― my practice, to be precise? It means spending time with exhibitions, books, periodicals, and other vehicles through which photographers disseminate their output. Nothing arcane about it, at least from my perspective. Mostly, like the Rowan Atkinson character in the 1997 comedy Bean: The Ultimate Disaster Movie, “I sit and look at the pictures.” Actually, not to get too technical about it, usually I stand when I’m looking at the pictures, because museums and galleries don’t offer seating opportunities as often as they once did. Then I go home, where I sit down to write about them. I’ve done this since 1967, and while I’ve gotten old doing it, the doing of it hasn’t gotten old. But the context that enabled me to earn my livelihood doing it has all but evaporated.

When I began publishing my commentaries on photography in 1968, I did so in large part because it seemed a matter of some urgency to jump-start a critical tradition for the medium, something that, inexplicably, it had lacked up till then. In his 1971 book The Pound Era the literary critic Hugh Kenner described the function this serves for the future, for history, for the ongoing life of a medium, in these words:

“There is no substitute for critical tradition: a continuum of understanding, early commenced. . . . Precisely because William Blake’s contemporaries did not know what to make of him, we do not know either, though critic after critic appeases our sense of obligation to his genius by reinventing him. . . . In the 1920s, on the other hand, something was immediately made of Ulysses and ‘The Waste Land,’ and our comfort with both works after 50 years, including our ease at allowing for their age, seems derivable from the fact that they have never been ignored.”3

Photography had been pretty much ignored by critics up through the 1960s; the work of only a few of its major figures, and fewer of its minor ones, existed within “a continuum of understanding, early commenced.” Beyond the poetics of photography, its then-disputed status as a medium for creative activity, there lay the much larger questions of its functions as a culture-wide visual communication system. Except for Marshall McLuhan and, before him, William M. Ivins, Jr., and before them Walter Benjamin, hardly anyone had thought those matters worthy of contemplation. All this struck me as fertile ground for inquiry, which I believed should take place before the broadest possible audience. Having become a freelance contributor to the Village Voice, a weekly forum for commentary on the arts, politics, and cultural issues, that seemed the logical place to start. So I did. My role models were my older colleagues at the Voice, as well as the art critic Sadakichi Hartmann, before me the most assiduous and consistent critic of photography, and James Agee in his work as a film critic for The Nation.

•

Some 40 years later, in August 2010, I found myself in the historic city of Dali, near Kunming in the province of Yunnan, southwest China, serving in the role of international advisor to the second edition of a small festival there, the Dali International Photography Exhibition. In that role I got interviewed by local, regional, and national press on several occasions. During one such discussion, which went into my background and early experience as a critic, the interviewer asked if ― based on what added up then to five years of exposure on my part to the mainland Chinese photo and art scene ― I thought an independent critic such as myself, and a critical scene such as the western one I’d described to this reporter, could emerge in China.

As a matter of blunt fact, I doubt very much whether in my lifetime that military dictatorship will move sufficiently toward the model of an open society that any critic will find it possible to voice his or her honest opinion without fear or favor. However, I’m diplomatic enough not to make that explicit in the Chinese press, especially since, as a consequence of my current marriage, I have extensive family in China, where reprisal against relatives of anyone disfavored by the government enjoys a tradition stretching back for millennia.

So, to quote Brian Eno, I chose a more oblique strategy for my response. For a true critical dialogue to emerge around any medium at any time or place, I explained to my interviewer, certain conditions must exist. It requires, at a minimum, the following:

- A cultural and editorial environment that encourages the free public exchange of ideas.

- A publishing industry in which critics can function independently in relation to the individuals and institutions about which they write.

- A creative medium that’s energized and in a state of ferment. That will attract attention from individuals interested in the medium who have a critical bent.

- An audience for that medium, even if only a small but devoted one, to serve as an initial readership and sounding board for critical response.

- Some publishers and editors of periodicals who see a value in serving that audience, and that medium, by providing editorial space for the critics.

- Sufficient compensation for those critics’ editorial services to enable them at least to scrape together a modest living.

I didn’t yet know enough about the art scene and photo scene in China, or the broader cultural scene there, I told him, to voice an opinion on the presence or absence of those necessary conditions. I added that while I’d found those ingredients available in sufficient quantity to enable me to sustain my own work during my start-up period, there had never been an abundance, and the supply had thinned drastically in recent years, in the States and elsewhere. So, I concluded with an attempt at tact, if China lacked an active critical dialogue about photography, it had company.

•

If the role of working photography critic has entered its Jurassic phase, then, one reason, certainly, has to do with the disappearance of anything resembling a support system for that enterprise.

This has never been a high-paying occupation; no one gets into it for the money earned by writing critical essays. As I recall, when I left the Village Voice in 1973 I got $60 for each weekly column. The closest I’ve ever come to job security was the 1970 offer of a staff position at the New York Times, which I turned down in order to remain freelance for the Times, the Voice, and other publications.

The freelance life, precarious in the best of times, isn’t for everyone. But I started out as such at a moment when you could still live la vie bohême on a bohemian income in a major art and photography center like New York, especially if, like me, your luxury of choice was free time and you were willing to reside in the most remote of the so-called outer boroughs. Growing up in the heart of that city from the early 1940s through the middle 1960s I’d known many people in the arts and creative professions who managed to thrive in the cracks, so I assumed I could do the same, and did, for a while. But then they started tuck-pointing the cracks and raising the rents, till now it’s become at best faux boho, a facsimile of bohemia. When people have to pay $5000 monthly for their living and working spaces, they won’t have much time for the life of the mind.

The fees I and my colleagues received for our articles, low at best, didn’t keep pace with inflation or the cost of living. Nor did spaces open up for photo criticism at newspapers and general-audience periodicals to the extent that I anticipated as the “photo boom” of the 1970s began. I pieced together a living from a mix of writing revenues (including what I earned from my first two books), freelance teaching, and lecturing. Hand-to-mouth existence didn’t appeal to me; I simply got used to it, but certainly understood when colleagues like Andy Grundberg and Shelley Rice left it behind to take full-time teaching jobs or executive positions in institutions that provided regular salaries, paid vacations, health benefits, and retirement plans, though they inevitably became only occasional writers with that decision.

Mind you, this was still the heyday of the print periodical. I’ve always believed that the cultural weight of serious discourse about any medium depends in part on the presence of that discourse in general-audience publications: newspapers and weekly or fortnightly or monthly magazines aimed at a broad educated readership with an interest in the arts. I also value the frequency of a readership’s encounter with a regular contributor to a given publication’s pages. That weekly, biweekly, monthly contact can achieve something akin to ongoing conversation, rather than the occasional chance encounter. But unless that conversation takes place in the same agora as discussion of politics, economics, film, television, and the events of the day, it’s inherently ancillary, a side dish on the cultural menu.

And it only becomes the equivalent of a conversation when readers interact energetically and publicly with the critics of a medium, via the “letters to the editor” pages of the periodicals in which the critics publish. I’ve written at length about the unresponsiveness of the audience for photography,4 so let me just say that the widespread absence of such feedback on the record provides no correctives for photo critics’ errors and excesses, nor any tangible encouragement for their production. It also makes those readers, no matter how numerous, invisible to editors and publishers, leading them to conclude, not unreasonably, that the dedication of editorial space to photo criticism does not benefit the circulation of their periodicals in any way. Criticism of any medium in general-audience publications, when not subsidized by extensive advertising, is particularly vulnerable to the consequences of a mute and passive readership.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m delighted to have had the opportunity to get published in small-circulation magazines like Ag and Hotshoe. As a writer I never know when or where my ideas will reach and resonate usefully with some reader who may not have access to my work in more widely distributed periodicals. And my numerous contributions to the medium’s “little” magazines have enabled me to get certain ideas into print. Still, any dialogue that takes place only in the pages of small-circulation academic journals or specialized publications like art and photo magazines defines itself automatically as marginal in relation to the larger culture. So I aspire to get read by thoughtful fellow citizens of the world who may have an interest in the subjects I explore without any professional connection to the field. Hence my stints at the Voice, the Times, much later the New York Observer, and most recently a handful of pieces for newspapers in mainland China.

As you probably know, the entire publishing industry entered crisis mode with the advent of the World Wide Web in 1993. Publishers of books and periodicals, having hung on to 19th-century models far too long, found themselves in deep trouble. They began hemorrhaging revenue and readers, both of which migrated to the internet. That led to their demanding that writers donate online rights to them for no additional payment ― the cause of my departure from the New York Observer, as I’m insistent on retaining my copyright and subsidiary-rights licensing options. Compensation for online usage of work like mine has never risen to the painfully low level of payment for print usages, so, whatever its virtues, and they’re many, the web did not represent a new revenue stream for myself or my photo-critical colleagues.

To the contrary, the web killed off many small, specialized print publications. Loss of circulation at larger publications led to loss of advertising, reducing the available budget for editorial content. That in turn has led them to a more reader-driven relationship to content, with the result that, in a steadily dumbed-down culture, Amy Winehouse, Kim Kardashian, Bruce Willis, Ashton Kutcher, and Demi Moore share front-page headline space with Arab Spring and the European financial crisis.

Should I go along to get along? Forinstance, I feel confident that I could find an editor at a major magazine who’d commission a feature on celebrities who photograph ― people like Jeff Bridges, Dennis Hopper, Diane Keaton, Karl Lagerfeld, Richard Gere. Some of them aren’t half-bad. If I’d started upright in my bed one midnight yearning to write that piece, I’d have done so. Instead, I cooked it up in a brainstorming session, half-heartedly trying to figure out what would sell instead of what I thought I should write next to make things hot for myself and my readers. That celebrities-as-photographers piece could turn into a lucrative book, even a traveling show, but it feels to me too much like sucking up to the rich and famous, or sucking up to the public’s appetite for news of same, and my heart’s never been in that.

On top of which, that assignment doesn’t require a photo critic, who may look at those images and decide ― as I did recently with the paintings of Bob Dylan ― that they’re competent and amiable but irrelevant to the medium’s field of ideas. I guarantee you that’s not what the editor who would commission such a feature would want to hear. No, that’s a job for a cultural journalist. Specialized critics like myself, not just in photography but in all the arts, have begun to give way to “cultural journalists” ― jacks of all trades who know a little about many things and not much about anything in particular. They write as naïfs. A prime recent example would be Jane O’Brien’s story, “Gertrude Stein celebrated at two Washington DC museums,” posted at BBC News Online on October 14, 2011, which opens forthrightly as follows:

“I’ve often wondered whether approaching a subject from a standpoint of total ignorance sharpens my investigative powers, or whether it simply leads to inevitable embarrassment from which I’ll never recover. That thought was uppermost when the National Portrait Gallery announced the opening of an exhibition on Gertrude Stein. Of course I’d heard of her ― wasn’t she that famous feminist who burned her bra in the 1960s? ― But beyond that I really had no idea who she actually was.”5

There you have cultural journalism in a nutshell, atypical only in the candidness with which its author confesses her incompetence for the task at hand and her editors’ and publishers’ willingness to lay on the table her lack of qualification for this assignment. To put it in our crude ex-colonial vernacular, O’Brien doesn’t know shit from Shinola, crows about it in her news story, and gets paid for doing so by the BBC. Whatever its entertainment value for equally uninformed readers, paraded ignorance such as this adds nothing to the critical dialogue about Stein specifically or modernism generally.

I’ve chosen this example to demonstrate that the problem doesn’t restrict itself to us bumpkins in the United States, knowing full well that doing so rubs salt into the wounds of residents of the sceptered isle, already smarting under the humiliating global scrutiny of its much grosser Fleet Street excesses. But that’s another discussion. More to the point, are you prepared for features, reviews, and interviews on subjects photographic ― postmodernist practice, street photography, Victor Burgin, Jo Spence, Julia Margaret Cameron, Bill Brandt, you name it ― by cultural journalists who readily declare themselves tabula rasa but eager to learn? Because, ready or not, that’s what you’ll get henceforth in the mainstream press.

So one of the cluster of meteors that struck my little world to send up a smothering cloud of ash has begun to eliminate the editorial support system for what I do professionally as a writer, by substituting cultural journalism’s one-size-fits-all daytrippers for staff or freelance specialized critics. Additionally, there’s another change in the market that results from a change in their readerships. The USA Today model has permeated the industry. Editors now ask for short, punchy pieces, the shorter and punchier the better ― 250 words (roughly one double-spaced typewritten page) is great, 500 words okay, 750 words ample, 1000 words windy, and anything much over that longer than one can expect today’s average readers to stay with to the end.

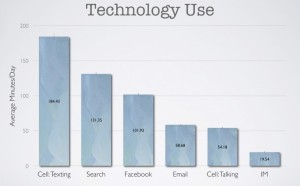

This is due partly to the widespread erosion of the ability to pay close and prolonged attention, for which we can hold the entirety of mass media and digital technology responsible, partly to the reading and writing habits of people who put in way too much time immersed in social media. Did you know that the average college student in the States today spends more than three hours a day doing email, instant messaging, and cellphone texting, plus another three hours surfing the web ― and that’s the demographic publishers hope to reach?

The problem is that, given as I am to thorough disputation, I can’t easily make the transition from essay form to the snippet, the text equivalent of the soundbite. I can extract substantive 250-word chunks from longer pieces much more easily than I can conceive and write them at that length by plan. Yet even when I do, I hear those fragments calling out to be reunited with the context from which I’ve severed them, like lost kittens mewing for their mother.

How does a critic compete with the claim on people’s attention today of social media? I have a Facebook page to which I pay absolutely no attention. I’m not on Twitter.6 My idea of blogging, as you know if you’ve visited me at Photocritic International, involves writing at my preferred length and dividing it into parts for posting if an essay runs much over 1200 words. So I genuinely have no idea how to do what I do in a much more condensed way. I do, however, give it thought. For example:

- Suppose I reconceptualize the 140-character “tweet” as a version of the form Allen Ginsberg named the “American sentence,” a 17-syllable prose counterpart to the 17-syllable Japanese haiku?

- Should I try my hand at incorporating “lolspeak” or “kitty pidgin” into my writings ― for example, taking on the role of Ceiling Cat, benevolently declaring that “Edwurd Westin can haz negatif spayse”?

How about simply making my ideas more accessible to the current generation by converting them from texts into other formats?

- Turn my essays into spoken podcasts and/or YouTube videos.

- Turn them into comics, and my collections thereof into graphic novels, or fotonovelas: A. D. Coleman for Beginners.

- Shift to a different model for my books: Postmodern Photography for Dummies, The Complete Idiot’s Guide To Group f/64, Photo-Based Art in 90 Minutes. With lots of highlighted sections, bullet points, and tips.

This probably sounds facetious, but I have in fact considered all of the above, and may well try my hand at a few. As I told some colleagues during a lecture last week in Bratislava, 2011 is not 1960, and the college-age audience today is made up of people young enough to be my grandchildren. I and the cohort of students to which I belonged in 1960 resembled the 20-something cohort that walks into my classroom or surfs to my blog today only in their physiology and basic psychological and emotional structure. Socially, culturally, and especially in their relation to information technology, they’re radically different from me, and from anyone born before the emergence of the internet and the World Wide Web.

On top of the texting and IM and chat I mentioned previously, they spend additional hours each day surfing online, then more time absorbing audio, video, and multimedia content ― on their computers, via their iPods and iPhones and Androids and Kindles and other electronic devices. These are their habitual relationships with technology. The abilities necessary to utilize these media also constitute skillsets, at which they are in most cases more adroit than I. Expecting them to set all this aside in order to work with my ideas in the form of printed texts exclusively, or even primarily, is simply unrealistic. So either I recognize and engage this cohort’s technological skillsets and media preferences or else I lose them (or, at the very least, lose all but that small percentage who’ve come to enjoy substantive ratiocinative prose). Which would leave me preaching not only to the converted but to a graying and dwindling subset thereof. Not an appealing prospect.

At the same time, they’re also habituated to obtaining the content they consume for free. If I go to the trouble of developing new skills so that I can multipurpose my content in forms they enjoy more, they’ll just swipe it ― and, like Kyle Newberry, diss me when I object. So why bother? Lately the theme song running in my head is Gillian Welch’s “Everything is Free.” You probably know its wry commentary on IP theft, which strikes a chord with me. However, her solution ― to sing privately, at home, for herself and those she loves ― doesn’t really work for a critic, whose activity is either public or pointless.

Let’s see if this old dog can learn some new tricks, while finding ways of making it pay for itself. Of course, I could use some help at this. I understand you can hire people to manage your social-media life for you, and it may come to that. But I’ve already created a video for YouTube, in my performance-art alter ego as The Derrière Garde; podcasting doesn’t seem all that hard; I’m reading Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics and Barbara Slate’s You Can Do a Graphic Novel; and a lolspeak post at my blog isn’t out of the question. Adapt or die, right?7

(To be continued.)

Part 2 of this essay will appear in Issue 3 of VJIC

Return to Issue 2 Table of Contents

(You are invited to add to the conversation below.)

References

- For my commentary on the kerfuffle that the text of this talk provoked at a popular photo-specific online forum, click here. ↩

- Ezekiel 37:3. ↩

- Kenner, Hugh, The Pound Era (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1971), p. 415. ↩

- See “The Destruction Business: Some Thoughts on the Function of Criticism,” in Coleman, A. D., Depth of Field: Essays on Photography, Mass Media and Lens Culture (Albuquerque, New Mexico: University of New Mexico Press, 1998), esp. pp. 2-4 and 21-22. ↩

- Online at http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-15314287. ↩

- No longer true. You can follow me there at @ADColeman1. ↩

- Subsequent to presenting this talk in London, I produced the first in a series of “Kritikomix,” Pepper-Spray Cop: The Comic, concerning the imagery that emerged from the infamous police attack on students at UC Davis, CA that fall. One version is a downloadable PDF file; another is a video, with voiceover. ↩