Theme Table of Contents

VJIC Table of Contents

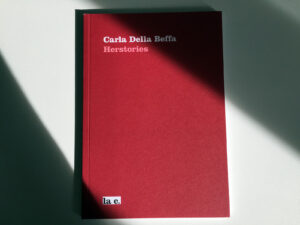

I’ve always had a good ability to listen, and to tell stories. Around 2017 I allowed myself to start writing them, drawing inspiration from what I had seen and heard. And that’s how Herstories was born: short stories of women I had met, some written in Italian, others in English. On one side I had the stories, on the other the images. The first task was to select the two components and combine them so they could enrich each other, prompting questions and answers.

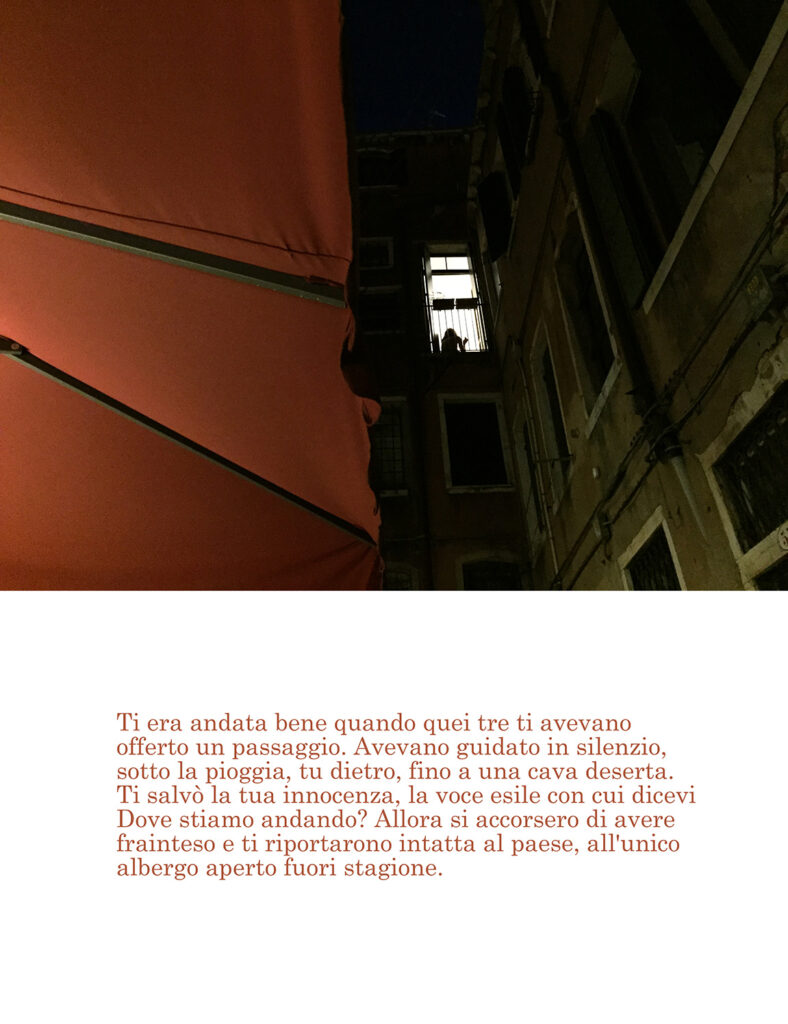

I had a few rules: every place and detail in the photographs clearly suggested human presence, yet among them all there is only one image where a living person can be glimpsed—a tiny silhouette behind a window. I alternated Italian and English, I, You, and She; when a story moved me too much, I wrote it in English and in the third person, to create some distance between the event and its telling. (There aren’t many artists like Nan Goldin, capable of photographing their own lives without filters. Cindy Sherman has always disguised herself to avoid revealing herself.) When I decided to turn it into a book, I chose to translate the texts into the other language. While working, I realized it was more interesting and more fun to create non-literal translations. Here is an example, with the Italian actual translation and my more personal one:

I had a few rules: every place and detail in the photographs clearly suggested human presence, yet among them all there is only one image where a living person can be glimpsed—a tiny silhouette behind a window. I alternated Italian and English, I, You, and She; when a story moved me too much, I wrote it in English and in the third person, to create some distance between the event and its telling. (There aren’t many artists like Nan Goldin, capable of photographing their own lives without filters. Cindy Sherman has always disguised herself to avoid revealing herself.) When I decided to turn it into a book, I chose to translate the texts into the other language. While working, I realized it was more interesting and more fun to create non-literal translations. Here is an example, with the Italian actual translation and my more personal one:

It had gone well for you when those three offered you a ride. They drove in silence, under the rain, you in the back, all the way to a deserted quarry. You were saved by your innocence—the thin little voice with which you asked Where are we going? Then they realized they had misunderstood and brought you back intact to the village, to the only hotel open in the off-season.

It had gone well for you when those three offered you a ride. They drove in silence, under the rain, you in the back, all the way to a deserted quarry. You were saved by your innocence—the thin little voice with which you asked Where are we going? Then they realized they had misunderstood and brought you back intact to the village, to the only hotel open in the off-season.

You were far away from home and quite lost. You asked for some information. You felt very lucky when those three gave you a lift, promising they were going to drive you there. Their car went under the driving rain, nobody speaking, to a deserted quarry.

You were saved by your innocence, the small voice when you said Where are we going? Then they knew they had misunderstood and brought you back to the small town they had just left, to the only hotel open in the dead season.

Thinking back to that night, after so many years, you still heave a sigh of relief. You were very lucky indeed. (You have always been quite lucky, actually. Every big risk you naïvely and trustingly took in your life was reduced to just a big scare, a memento, never becoming the deadly accident it could have been. After all, you prefer trust and optimism to diffidence and fear.)

I have always enjoyed playing with words. The title of the project, which has been exhibited in Italy and abroad, is the plural of herstory, a term coined by American feminists (first known use, 1962). They played on the pronouns her–his to challenge History as a list of events made by men: his-tory. They wanted to include women—and not only queens or abbesses—in historical events. Since 1947, French scholars at the École des hautes études en sciences sociales (EHESS) had begun collecting and analyzing data and information about the lives of ordinary people, so that their story could be told as well. Some dug into the account books of the Duke of Burgundy to learn the basic diet of the time (the family had to be fed every day, but also the stable-hands and laundresses, not to mention hosting guests and their retinues with proper dignity); others told the history of water and fountains in Paris, where the women of the city queued every day with their buckets and pitchers. And yet women’s roles continued to be invisible in the one History taught in schools. Artists of the past were “very good, for being women,” wrote Germaine Greer and other feminists in their histories of art. For poets and writers, recognition arrived somewhat earlier—but by decades, not by centuries (it’s no coincidence that Jane Austen signed with a male name). And as Siri Hustvedt brilliantly argues in The Delusions of Certainty, science, medicine, and law claim to be objective, yet rest on a millennia-old tradition in which male is the default.

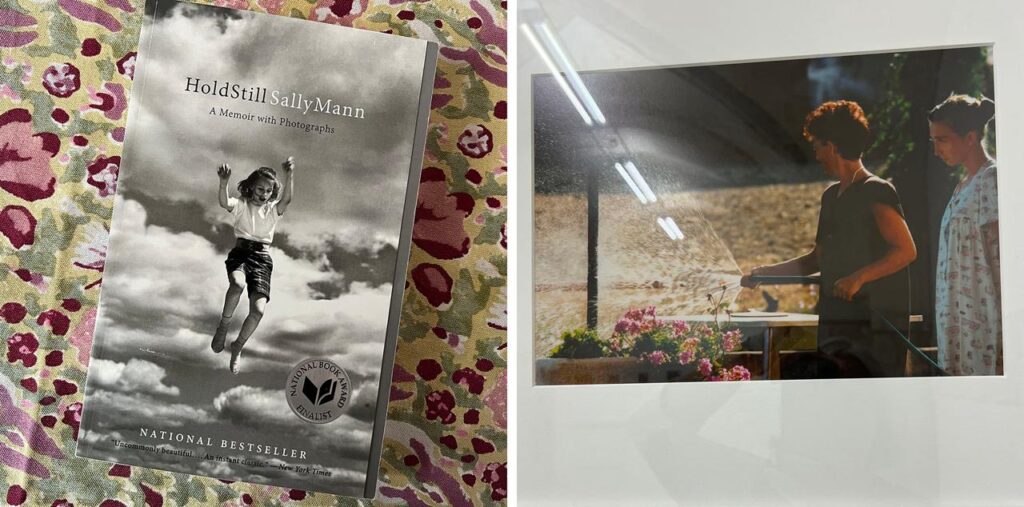

Sally Mann – Moira Ricci

In photography and books, I find women such as Silvia Camporesi, who after years of photographing monuments and landscapes decided to portray rescue teams covered in the mud of a flood. There is Sally Mann’s memoir Hold Still, with the story and photographs of her family: wonderful to read and to look at. There are Moira Ricci’s photomontages, where she inserts herself—without AI—into family photos in which her young mother is working or watering plants. I speak only of moments, of emotions, and I combine them with images without people. Here is what Cristina Viti, poet and translator of poets, writes in the introduction:

Con Piacere (With pleasure): 200 words on Carla Della Beffa’s Herstories

art: work: vital tension: dynamic interaction of opposites: energy created & circulated by a disciplined refusal of resolution: poised balance: razor-sharp observation, crystal-clear images: warmth, amity against generic & ultimately stereotyping solidarity: relating: seeing deeply & touching tenderly: non-judgment, a militancy of the image: freedom hard won & elegantly carried: colours, a long & intimate relationship with colour: machines as prompts for a critical reflection on systems: grace under fire: pure joie de vivre, laughter, dance, élan: fashion as play, taste as praxis: understatement as a focusing evice for human kindness against emotional self-indulgence: travel, openness to risk & surprise: cities, their glamour, their miseries: economies of image & self-image: myth & fairy tale revisited with humour: skill, technique, the love of things done well: the detail as keystone: memory as lucidity wrestling with nostalgia: the world & the neighbourhood: the body & the family: the body & the workplace: the body & its transience, its freedoms & fragilities: the shutter’s split second: ‘foreign language’ with no pretension: ‘mother language’ with the ease of daily conversation: language observed: consciousness raising & urban acceleration: complacent assumptions whether one’s own or others’ relentlessly challenged: there is so much more… go find out.

art: work: vital tension: dynamic interaction of opposites: energy created & circulated by a disciplined refusal of resolution: poised balance: razor-sharp observation, crystal-clear images: warmth, amity against generic & ultimately stereotyping solidarity: relating: seeing deeply & touching tenderly: non-judgment, a militancy of the image: freedom hard won & elegantly carried: colours, a long & intimate relationship with colour: machines as prompts for a critical reflection on systems: grace under fire: pure joie de vivre, laughter, dance, élan: fashion as play, taste as praxis: understatement as a focusing evice for human kindness against emotional self-indulgence: travel, openness to risk & surprise: cities, their glamour, their miseries: economies of image & self-image: myth & fairy tale revisited with humour: skill, technique, the love of things done well: the detail as keystone: memory as lucidity wrestling with nostalgia: the world & the neighbourhood: the body & the family: the body & the workplace: the body & its transience, its freedoms & fragilities: the shutter’s split second: ‘foreign language’ with no pretension: ‘mother language’ with the ease of daily conversation: language observed: consciousness raising & urban acceleration: complacent assumptions whether one’s own or others’ relentlessly challenged: there is so much more… go find out.

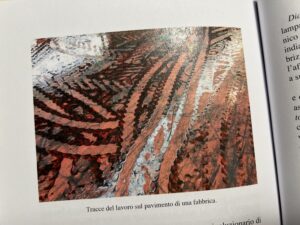

Over the years, I have dealt with economics, society, and relationships. I inserted words and marks into photos, to explain myself better, and because my images didn’t seem enough. With Herstories I finally acknowledged that words had a role equal to images. Perhaps tomorrow I will no longer need them, or only for certain stories—like that of a toy factory to which I dedicated a ten-copy book, Gita alla Faro. The truth is that I like words so much, and I can’t do without them.

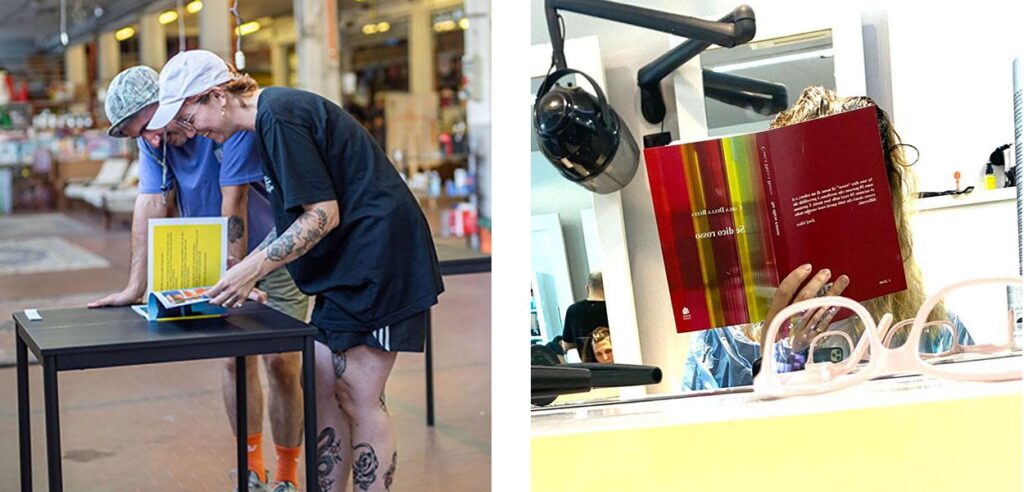

Gita alla Faro – Se dico rosso

And now there is a surprise I hadn’t foreseen when planning this installment: Se dico rosso (BookTime–La Vita Felice, Milan 2023). It is an essay on colors and on the words we use to define them. It is a rainbow of ideas and hues, with many words and quite a few photographs, and the title is borrowed from a lesson by Josef Albers on color and perception. The cover says:

And now there is a surprise I hadn’t foreseen when planning this installment: Se dico rosso (BookTime–La Vita Felice, Milan 2023). It is an essay on colors and on the words we use to define them. It is a rainbow of ideas and hues, with many words and quite a few photographs, and the title is borrowed from a lesson by Josef Albers on color and perception. The cover says:

Se dico rosso is an investigation into the words of colors, an enormous puzzle impossible to solve, so rich is it in clues and points of view. Chemistry, codes, pigments, the physical causes of color, the workings of light and perception, catalogue names and metaphors, art history, criticism, morality,  literature,songs. Words and colors touch everything and everyone, from art to architecture, from candies to nail polish, from fashion to industry. In Italian, English, and French the names of hues change, and their symbolic value differs in every culture. Interpreter, witness, detective, Carla Della Beffa has spent years digging into the theme of color and its languages to gather data and arguments, then stitching together words and photographs, comments and translations, like a patchwork. Infinite and necessarily incomplete, because it is vision that gives color to things: colors exist only if there are eyes to see them. And what we see is subjective: even facing the same shade, each of us sees our own red.

literature,songs. Words and colors touch everything and everyone, from art to architecture, from candies to nail polish, from fashion to industry. In Italian, English, and French the names of hues change, and their symbolic value differs in every culture. Interpreter, witness, detective, Carla Della Beffa has spent years digging into the theme of color and its languages to gather data and arguments, then stitching together words and photographs, comments and translations, like a patchwork. Infinite and necessarily incomplete, because it is vision that gives color to things: colors exist only if there are eyes to see them. And what we see is subjective: even facing the same shade, each of us sees our own red.

The next installment will be an interview with two artists—two men full of initiative who make books and much more—and I will start from one of their almost-wordless photo-books.

The next installment will be an interview with two artists—two men full of initiative who make books and much more—and I will start from one of their almost-wordless photo-books.