Theme Table of contents

VJIC Table of Contents

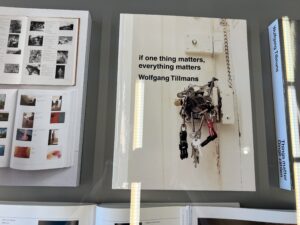

Hi, I’m Carla Della Beffa, I’m a visual artist and writer from Italy, my contribution will be about books: photo-books, artist’s books, and in between. I use digital photography, don’t have a bag full of lenses—I want to stay light. I like to notice a neglected detail and tell the story of what it hides. A bit like Wolfgang Tillmans, who will never know it but is my spirit guide, for his ability to appreciate and photograph everything. Everything matters: not by chance, one of his books is titled If one thing matters, everything matters.

Every author has specific method and processes in choosing what to see and shoot, what to put in a book. The how and why. I will talk about mine, and some others’, in this article and in the few that will come next.

In my work, I combine small things and small stories to reach a bigger story—one that concerns the experience of many, if not everyone: economy, food, colors, travel, women, light. To do this, I can add lists of words, signs, stories, or create image sequences. It depends on the idea, and on my confidence in myself, in that moment, in that project.

In 2002, after an exhibition at the online art gallery of the University of Auckland, NZ, curated by Luke Duncalfe, I published a book, la cucina italiana: just a few pages, 50 numbered and signed copies. Images of food, with the name and its phonetic transcription. Because everyone loves Italian food, but they don’t always know how to pronounce it. Because I wanted it to be an Italian project but not a tourist cliché. And also because when I write, when I read, I hear the sound of words.

In 2002, after an exhibition at the online art gallery of the University of Auckland, NZ, curated by Luke Duncalfe, I published a book, la cucina italiana: just a few pages, 50 numbered and signed copies. Images of food, with the name and its phonetic transcription. Because everyone loves Italian food, but they don’t always know how to pronounce it. Because I wanted it to be an Italian project but not a tourist cliché. And also because when I write, when I read, I hear the sound of words.

If I have an important series, at some point I turn it into a book. The first reason is that I want to refine the idea, define it, make it alive and concrete. Bring it out of me. Touch it, instead of just having it in my mind or on the computer. Often, exhibitions follow the book. The motivation changes: a book project isn’t the same as an exhibition project. The book is part of the artwork; the exhibition comes later, once the work is finished, and makes it known. The method changes too: there are images, and there is narration. The text isn’t a caption, but it creates a dialogue with the image, giving it another depth (I learned that in my previous life, years of a career in advertising). Even Goya’s etchings have titles that provoke thought, beyond the caption. Sometimes photos stand on their own and need nothing else. Unfortunately, it’s not always possible to make books or exhibitions: some works wait years, and some wither away. They stay there, a bit sad, overtaken by events, by time.

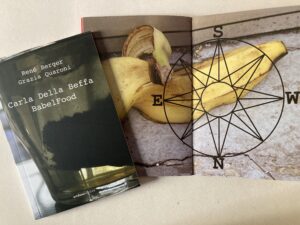

BabelFood is a 2005 book, a project on the history and journeys of food. The photos are part of the series of the same name, marked with an upside-down compass rose. The idea was to recall what we often forget: foods like potatoes and tomatoes, and drinks like coffee, were imported into Europe after 1492, and took a long time to enter our habits. Bread and wine—that is, wheat and vines—came from the Middle East with the nomadic peoples of antiquity. A kind of pizza existed in Roman times, without tomato or mozzarella: just bread, wild herbs, a bit of oil and salt. Wars were fought over salt. “Zucchero” (sugar) is an Arabic word.

BabelFood is a 2005 book, a project on the history and journeys of food. The photos are part of the series of the same name, marked with an upside-down compass rose. The idea was to recall what we often forget: foods like potatoes and tomatoes, and drinks like coffee, were imported into Europe after 1492, and took a long time to enter our habits. Bread and wine—that is, wheat and vines—came from the Middle East with the nomadic peoples of antiquity. A kind of pizza existed in Roman times, without tomato or mozzarella: just bread, wild herbs, a bit of oil and salt. Wars were fought over salt. “Zucchero” (sugar) is an Arabic word.

The series includes bread, strawberries, sacks of potatoes, Martini cocktails with olives, sushi, Campari at sunset, bananas, chocolates, rice eaten with chopsticks. Many journeys and exchanges: historical and cultural, as well as economic. The Italian trattorias in NYC with red-checkered tablecloths were opened by immigrants, like the Indian, Chinese and Lebanese restaurants and the ubiquitous kebabs. Changing ingredients and recipes, the same logic applies everywhere, across centuries: Japan drank tea and sake, today it exports excellent whiskies and beers. Tsarist Russia invited great Italian chefs to court; from Russia we received vodka. The Catholic Church spread bread and wine as far as northern Europe, and with the rule of meatless days created an international market for dried and salted fish. BabelFood also included two short essays by Grazia Quaroni (Fondation Cartier pour l’Art Contemporain, Paris) and the late René Berger, a Swiss intellectual and critic of great experience and courtesy.

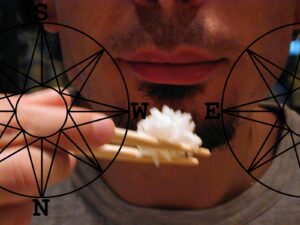

In the book, the images are mixed with others that reinforce my statement of those years—about affection, words, and food: all possible forms of orality. Kisses, words and food: the mouth is the place where most of my works begin.

The third book I want to include in this article was created around the same time, in 2003. It’s the chronicle of a train journey along the entire Adriatic coast, from Venice to Otranto. I started it because I wanted to make myself better known to a French curator. Every day I sent her blue-written postcards, inviting her to imagine what I was seeing, living, photographing. She never replied, but I summarized the trip in a book printed in 20 copies—art postal (mail art). The montage is chronological. The captions are the phrases I sent her: invitations to imagine the heat, the noise, the encounters—the whole journey, from departure to return home.

The third book I want to include in this article was created around the same time, in 2003. It’s the chronicle of a train journey along the entire Adriatic coast, from Venice to Otranto. I started it because I wanted to make myself better known to a French curator. Every day I sent her blue-written postcards, inviting her to imagine what I was seeing, living, photographing. She never replied, but I summarized the trip in a book printed in 20 copies—art postal (mail art). The montage is chronological. The captions are the phrases I sent her: invitations to imagine the heat, the noise, the encounters—the whole journey, from departure to return home.

A self-published artist’s book in digital form and a few copies can cost very little, and I can do it however I like—choosing fonts, paper, colors, format. The cost is part of the artwork, like the canvas and paint for a painter. But there’s no ISBN, no barcode: I can only sell it as if it were a photograph, a painting or an etching. In fact, it’s a multiple.

A publisher has a different kind of budget and costs, and the number of copies is higher. If they accept me and are good, they’ll proofread, correct mistakes, do some promotion, and have a distributor—but they impose constraints on style, colors, format, type of paper. Yet let’s not kid ourselves: there are so many books, and very few bookstores will order ours. Perhaps none. But it’s still a book, and we can exhibit it, or send it to festivals and competitions—there are many (for artist’s books and for photography book sections). I know people who win often. And there are some specialized bookshops-galleries that also accept volumes without barcodes. Another option is print-on-demand (POD) books: laid out using Amazon or similar templates, printed when ordered, and shipped to the buyer.

In the first phase of each project, I take a huge number of photos, make one selection after another, then start adding texts or marks. I choose again, write, rewrite, and go on like that until I feel ready.

Sometimes I print a few proofs, but most of the work happens on the computer. When I decide on a layout—which also depends on the publisher and costs—I start inserting texts and images. I work at the monitor, continuing to discard, select, and fine-tune elements until it’s time to print. Words help; they act as a guide. If I’m not convinced, I redo. Some of my books have gone through five major revisions, changing formats—horizontal, vertical, large, pocket-sized—colors, fonts, text structure, and content.

When I write, the moment comes when I need someone’s opinion. If the reader interprets the manuscript differently from my intention, I know I haven’t explained myself well, and I rewrite it. It’s not that they didn’t understand—it’s that I made a mistake somewhere.

The sequence of images is defined much like in video editing: it depends on where I want to go, on the story I want to tell. This time it was about food and travel; next time it will be essentially about women.