Theme table of contents

VJIC table contents

|

This way to |

The Greatest Show Online:

P. T. Barnum and AI

5.1 Edward Bateman. P.T. Barnum and General Tom Thumb, 1860/2025. Video.

The remarkable may seem impossible and challenge our credibility, but it always gets our attention. And sometimes, it is even true. Bateman’s short video is based on Samuel Root or Marcus Aurelius Root, P.T. Barnum and General Tom Thumb, 1860. 6.06 x 9.76 inches. Daguerreotype (half-plate). National Portrait Gallery, Washington, DC.

P.T. Barnum (1810-1891) did not just put on a show—he built a stage for the American imagination. Decades before the Metropolitan Museum of Art opened its solemn, marble halls, Barnum’s American Museum (1841-1865) had already welcomed millions, promising “wonders never before witnessed by mortal eyes!” There were giants and dwarfs, whales in basement tanks, mummies that may have once been kings—or maybe not. A mermaid might be a monkey sewn to a fish. But no matter. The thrill was real, even if the facts were negotiable. And then there was the sign: This way to the Egress. Eager visitors followed it, expecting another marvel… only to find themselves unceremoniously ejected onto the street. It was Barnum’s favorite prank. Not cruel, just a lesson in assumption, wrapped in a joke. He understood that people do not always want the truth; they want the feeling of discovery. In an age of wax figures and trick mirrors, Barnum did not have to lie. He just had to let people keep guessing.

Barnum was not just a master of spectacle, he was also an early adopter of photography. His likeness, and that of performers like General Tom Thumb, circulated widely as cartes de visite, transforming showmanship into collectible evidence. In this way, Barnum anticipated photography’s role as proof, publicity, and performance well before the scrollable feed. He shaped the visual economy of the nineteenth century social media through his notion of humbug. [1]

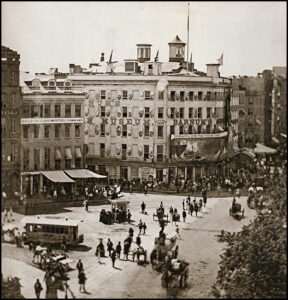

5.2 William England. Barnum’s American Museum, New York City, 1858. 3½ × 7 inches (stereograph). Albumen print.

5.2 William England. Barnum’s American Museum, New York City, 1858. 3½ × 7 inches (stereograph). Albumen print.

This stereograph of Barnum’s famed Broadway museum captures the façade of one of America’s most popular cultural attractions in the nineteenth century. Mixing natural history, theatrical spectacle, and outright humbug, Barnum’s museum epitomized the blurred line between education and entertainment that defined mid-Victorian popular culture. England’s photograph preserves the building, which burned down in 1865, offering a visual record of Barnum’s showmanship at its peak.

Today, all the world’s wonders are a tap away on your phone. Scientific proof of a mermaid? CLICK. The most beautiful woman in the world? CLICK. The secrets they do not want you to know? CLICK. A camelopard? CLICK… even if it’s just a giraffe. Algorithms now automate Barnum’s spectacle-building, feeding us novelty, confusion, and desire on demand. Barnum sold the experience of the experience. He leaked details, teased acts, curated astonishment, and sequenced emotions like a DJ to build awe and end with wonder. His exaggerations were hyperbole-as-honesty. Audiences knew they were being sold a spectacle, but they wanted the thrill. It was not just what they saw, it was how it made them feel: awe, disbelief, glee, and a gratifying sense of superiority. It was a collaborative illusion engineered for emotional velocity.

Just as Barnum manipulated expectation to heighten emotion, photographers have long framed their images to shape belief. From its beginnings, photography was never an impartial witness. Spirit photographers like William Mumler, sold images of dead relatives to grieving families; images of the Spanish Civil War manipulated battlefield realities for propaganda; and newspapers have long altered, cropped, or staged photographs to sway opinion. The medium’s claim to truth was always a matter of cultural trust, its indexicality always entangled with manipulation. AI does not break photography’s link to disbelief, rather it automates and accelerates it, pushing the continuing tensions between fact and illusion to the brink. These examples remind us that photography’s legacy has always contained both wonder and deceit with AI being the latest chapter.

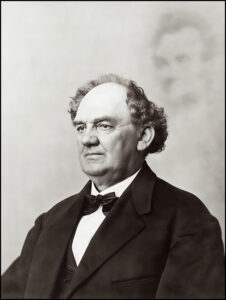

5.3 Abraham Bogardus. P. T. Barnum and the Spirit of Abraham Lincoln, 1869. 4.25 × 6.5 inches. Albumen silver print.

5.3 Abraham Bogardus. P. T. Barnum and the Spirit of Abraham Lincoln, 1869. 4.25 × 6.5 inches. Albumen silver print.

In April 1869 William Mumler was brought to trial for fraud. Barnum testified against him. To prepare he asked Abraham Bogardus to make a spirit image of Abraham Lincoln can be seen floating behind Barnum’s right shoulder. Barnum wanted to demonstrate that spirit photographs can be easily manufactured by any competent photographer. At the trial Barnum made a point to differentiate between his own ‘humbugs’ and those of the spirit photographers. He argued that despite his reputation for misleading the public, “I have never been in any humbug business where I did not give value for the money.” [i]

The computers we have known, loved, and cursed operate with simple algorithms. Does anyone double-check the results from their calculator? We have come to trust the results relying upon them as an authority. AI does not calculate; it imitates. It generates rather than computes, infers rather than reasons. Also, it seems to have a personality that learns to reflect the individual user. This encourages us to respond as if AI is human: polite, insightful, even wise, but sometimes crazy. [3] Nevertheless, that too is part of the illusion. Today’s AI is not nefarious; it is simply indifferent, powerful, and persistent.

Our eyes have been commodified. Looking has become a form of currency, especially online. The gaze carries both power and profit, a dynamic Barnum understood well. He capitalized on this by realizing that attention could be sold and that curiosity, even when tinged with disbelief, was good for business. And just as people did in Barnum’s day, we tend to stop scrolling for three kinds of images. First is the familiar, such as the face of a friend, a dog, or a favorite place, the things we recognize and feel comforted by. Second are surprising images that defy our expectations or credulity by creating cognitive dissonance or resisting instant categorization. Our brains crave pattern completion. When we cannot instantly classify an image, that tension keeps us looking. In both cases, our gaze is predictable, exploitable, and profitable. Third is sexual allure and excitement that is deeply rooted in human biology.

Barnum understood that attention blooms at the edges of understanding and on the fringes of recognition. He sold not only marvels, but the pleasure of figuring them out. If you believed his Feejee Mermaid [4] was real, you felt wonder. If you saw through it, you felt clever. Either way, Barnum thrived. It was a collaborative illusion, and the paying audience felt smart for participating.

Who among us truly doubts our own critical judgment? It is always someone else who is easily deceived, it is never us. But if we are honest, we should admit that we are frequently complicit in our own deceptions and that we might even enjoy them. Whether we are amazed, aroused, or skeptical, we are engaged. That is the real mechanism at work in AI-generated imagery: it does not matter what we experience as long as we keep looking. However, unlike Barnum, today’s AI illusions arrive without acknowledgement; without a wink, a hat tip, or curtain to peek behind.

From Critical Distance to Complicit Belief

Critical thinking is not a lost art, but it may be a neglected one. Naiveté is often a flaw we project onto others: the credulous neighbor, the Facebook uncle, the zealot, or the conspiracy theorist. Genuine skepticism turns the lens inward. Effective critical thinking does not assume truth; it interrogates it. It does not confirm our beliefs, it contests them. And crucially, it leaves room for change. Ironically, conspiracy theories mimic this structure, but corrupt it. They often emerge not from ignorance, but from intelligence misapplied: to buttress already accepted conclusions. The danger is not thinking, but thinking without friction, thinking that refuses to be open to additional reliable data.

5.4 Unknown maker. The Pope in the Puffer Jacket, 2023. Variable dimensions. AI-generated image.

The seamless realism of this AI-generated image blurs authenticity and satire, demonstrating how digital illusion now mirrors belief itself by inviting viewers to oscillate between amusement, awe, and doubt. Barnum would approve.

The digital free-for-all of social media is what makes AI-generated images and narratives so dangerous, and so seductive. Their plausibility invites belief, especially when the story aligns with our emotional expectations. Like Barnum’s Feejee Mermaid, today’s viral image or deepfake does not need to be true. It just needs to be close enough, trading on what we want to believe. And just as Barnum offered both wonder and a sly opportunity to see through the humbug, today’s AI-generated content offers the same binary: we are amazed and delighted or we spot the trick and feel clever. Either way, we are hooked with our engagement guaranteed.

Barnum stood beside his illusions, however today’s digital humbug, once initiated by a person, is automated and anonymous. The trickster, or worse, has no face and does not sign its work. AI can blend in seamlessly with actual photographs, historical documents, and human memories, making it difficult to determine the difference between it and human produced photographs, videos, music, and even books. At the present rate of technological advancement, all existing ways of validating truth could soon be useless. Previously, one might wonder if a photograph was staged, but this has given way to the question: was this image even made by a human?

The click of the camera shutter has been replaced by the click of a mouse or a tap on a phone. Both can take pictures and make choices. Gone is the unvarnished story told by a family photo album where every image was precious and irreplaceable. When editing did occur, it left a physical mark. It was a messy, aggressive act that required scissors, ink, or tearing. A falling out with a friend, the end of a romance, or a bitter family dispute could leave their mark directly on the photographs that preserved them. Severing ties often meant literally cutting people out. Some would carefully trim around a figure, leaving the rest of the photograph intact, but with an empty gap where a familiar face once appeared. Others were less precise, hacking out entire portions of the image so that a body or group photograph looked strangely mauled.

5.5 Unknown maker. Three people at a graduation ceremony, circa 1950. Gelatin silver print.

5.5 Unknown maker. Three people at a graduation ceremony, circa 1950. Gelatin silver print.

Before digital imaging made it easy to delete a name, block a profile, or erase a face, “unfriending” required a physical act of erasure. Rare Historic Photos, September 7, 2025. “Unfriending Before the Internet: The Vintage Way of Erasing People from Your Life and Photos.” https://rarehistoricalphotos.com/unfriend-before-internet/

Today, the family album and personal scrap book have largely vanished, replaced by the trove of images on our phones and posts on social media. To delete an image on one’s phone is to remove a moment from out personal history; if one ever bothers to sort through the vast sea of images. Social media, while edited, is a highly simplified and often is idealized fiction. Writer and essayist John Barth observed, “the story of your life is not your life, it’s your story.” [5] Perhaps it has always been so. Even in our minds, we construct, embellish, and fabricate our own personal histories into narratives. Maybe today’s younger generation already sees any mediated experience as a form of fiction and reality as a concept to be doubted?

AI allows photography to be more akin to a writer of fiction than a reporter delivering quotes. And with that comes the clandestine ability to claim authority through emotional images that distort actual events in order to promote dangerous and malicious cultural and political agendas. [6] This calls into question our personal and collective faith in photography’s indexical nature, thus risking the collapse of truth at the intersection where memory, evidence, and inheritance meet, destroying our shared sense of reality. With computer–users spawning new divided realities, how will anyone know what was real and what was fabricated?

5.6 Unknown maker. I love the smell of deportation in the morning, 2025. AI generated meme. https://truthsocial.com/@realDonaldTrump

5.6 Unknown maker. I love the smell of deportation in the morning, 2025. AI generated meme. https://truthsocial.com/@realDonaldTrump

Posted under the “White House” tag and bearing a caption that appears to come from the president, this image blurs the line between official communication and political performance. It raises questions about authorship and responsibility: Who is the true creator? Is it the person who conceived the idea, the one who wrote the AI prompt, or the individual who posted it? And if it mimics the voice of a sitting president, does that make him its author? In the age of synthetic media, attribution is no longer just about who made the image, but about who it appears to speak for.

Beauty, AI, and the Beholder

Visual seduction is nothing new. From its earliest days, the camera has been entangled with desire: posing beauty, selling attraction, and shaping ideals. Barnum understood this instinct. Although his American Museum was billed as family entertainment, he was not above leveraging erotic allure, which he rebranded as beauty and exoticism under the cover of refinement. His most infamous example may be the Circassian Beauties, circa 1865. Unable to acquire actual Circassian women, Barnum masqueraded and trained local performers as exotic women. When questioned, Barnum claimed beauty was in the eye of the beholder, even as he staged them as mysterious, foreign women for profit.

5.7 Mathew Brady Studio. Zalumma Agra, Circassian Beauty, circa. 1865. 3 3/4 × 2 5/16 × 1/16 inches. Albumen print/stereo card. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; Frederick Hill Meserve Collection, Washington, DC.

5.7 Mathew Brady Studio. Zalumma Agra, Circassian Beauty, circa. 1865. 3 3/4 × 2 5/16 × 1/16 inches. Albumen print/stereo card. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; Frederick Hill Meserve Collection, Washington, DC.

“Circassian” referred to people from the Caucasus region (modern-day southern Russia/Turkey). In the nineteenth-century Western imagination, Circassian women were mythologized as the most beautiful women on earth: light-skinned, exotic, and supposedly coveted for Ottoman harems. Abolitionists all played up this myth as a way to contrast “white slavery” with African slavery, feeding racist and colonial ideologies. Their wild, frizzed-out hair teased into enormous halos was achieved with soap, lye, and back-combing.

We see similar strategies at work on today’s social platforms, where beauty, desirability, and engagement are the currency of influencers. The erotic, implied or overt, becomes part of the visual economy. On Instagram, beauty is often framed as aspirational; on TikTok, it’s masked in trends; on OnlyFans, it is the business model. The gaze still sells, but now it is monetized through clicks, likes, and follows.

AI has already begun to colonize this space. AI-generated influencers, some fully synthetic, others human-machine hybrids, blur the line between digital performance and real desire. These avatars accumulate followers, partnerships, romantic fanbases, and even act as unlicensed psychological councilors. They are tailored to audience preference, trained on oceans of real-world images and text, and fine-tuned for maximum appeal. Plus, unlike human models, they do not age, complain, or demand royalties and unlike reality, they do not break the illusion.

5.8 Hailuo AI’s Minimax Generator Captured image stills from a video demonstrating the app’s capabilities to generate believable facial expressions.

5.8 Hailuo AI’s Minimax Generator Captured image stills from a video demonstrating the app’s capabilities to generate believable facial expressions.

Emotionally responsive faces can anthropomorphize AI and also generate more compelling deep fakes. This can only heighten the ethical and psychological risks. We have already seen individuals form unhealthy emotional bonds with AI systems through words alone.

As with Barnum’s Circassians, fabrication is not a flaw, it is a feature. We participate not in spite of the illusion, but because of it. The moral stakes, however, have changed. AI-generated bodies advance profound questions about identity, ownership, exploitation, and what it means to be seen, or duplicated, without consent. This raises the critical question: if the image is this seductive without being real, what happens to our shared sense of what is possible and genuine?

Finale: Beyond the Egress

AI did not mysteriously appear; rather it emerged gradually, a machine of imitation, not invention. It mimics not just our language and images, but our assumptions, desires, and fears. We respond to AI as if it were sentient, not because it is, but because it mirrors us well enough to fool the eye, flatter the ego, or save us mental and/or physical effort. [7] This encourages people to confide in, collaborate with, and even form intimate relationships with systems that simulate understanding without possessing any, all while we continue investing our resources in building more of them. Despite unknowable future consequences, it is a seduction that is seemingly hard to resist.

It’s not enough to recognize illusion; we must also decide what kind of world we want to build with AI. This requires artists, educators, lawmakers, philosophers, scientists, and others who share the desire to create, who understand how the social order, evidence, perception, and power operate to be able to confront those who profit from intentional confusion and outright lies. AI is a powerful tool, but as of yet it does nothing of its own accord. It is only an enabler that can be a social-political force that allows bad actors to generate disinformation.

Barnum relied on human performers, but today’s galleries, newsrooms, and social feeds are increasingly filled with AI-generated bots that shape our beliefs and behaviors. Will these tools elevate culture and deepen understanding or will they flatten experience into spectacle and thought into mere reaction? Will AI become the prime mover of art and culture or will it erode the very standards that allow us to value such things?

We now stand in a liminal space, where illusion and reality are algorithmically intertwined. If Barnum’s “humbug” was analog, staged, and fleeting, AI’s version is digital, masked, and persistent. It does not deceive, it empowers anyone to heighten duplicity, personalizes it, optimizes it, and directly targets its audience.

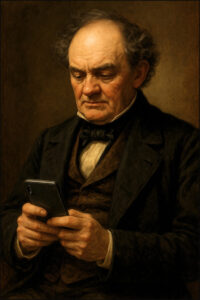

5.9 Robert Hirsch. P.T. Barnum in the Age of AI, 2025. Variable dimensions. AI-assisted digital portrait created with OpenAI’s DALL·E model under the direction of the artist; no copyrighted source material was used.

5.9 Robert Hirsch. P.T. Barnum in the Age of AI, 2025. Variable dimensions. AI-assisted digital portrait created with OpenAI’s DALL·E model under the direction of the artist; no copyrighted source material was used.

The issue that AI brings front and center is: Whom do you trust? The relationship between art and truth has never been straightforward. Pablo Picasso said: “Art is a lie that makes us realize the truth, at least the truth that is given us to understand.” [8] This assertion recognizes that art often operates in the space between truth and illusion. If that unsettles us, makes us question, or compels us to think, then perhaps art has done its work. Photography has always resided between art and evidence, index and illusion, which AI has intensified. If AI-based work taps into something deep in us, something beyond the boundaries of what we thought was possible, that would be a gift. In the hands of thoughtful artists, AI could awaken our imaginations and astonish us with previously unforeseeable images that evoke photography’s earliest legacy: Changing how reality is perceived and remembered.

Will we be AI’s audience, its ringleaders, or its next featured act? The rise of generative tools raises a question we can no longer ignore: What role is left for human imagemakers when machines can generate visual content on demand? Photographs have always relied on context and provenance to read their meanings. And now, the written word has seemingly become less important than images as we seek digital stimulation. The clearest path forward may be one of proven insight: To look closely, to think critically, and to remember that seeing is never passive.

Perhaps, what we are seeing is not a crisis in photography, but a failure of the imagination. What photography has been in the past does not define what it will be in the future. Ultimately, the history of photography is one of constant change and reinvention that allows the medium to be an artistic language of inexhaustible possibilities. It reminds us that looking deeply, whether at an image, idea, or illusion, offers the opportunity to discover the world.

Endnotes

[1] In his autobiography, The Life of P. T. Barnum, Written by Himself (1855), Barnum wrote: “Humbug consists in putting on glittering appearances—outside show—novel expedients, by which to suddenly arrest public attention, and attract the public eye and ear.” He additionally said: “A little humbug is necessary to tickle the public palate… the public appears disposed to be amused even when they are conscious of being deceived.” The key was mutual consent and enjoyment, rather than roguish deception or exploitation.

[2] Louis Kaplan, The Strange Case of William Mumler, Spirit Photographer, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press: 2008, 218.

[3] Kashmir Hill and Dylan Freedman, “Chatbots Can Go Into a Delusional Spiral. Here’s How It Happens,” The New York Times, August 8, 2025, www.nytimes.com/2025/08/08/technology/ai-chatbots-delusions-chatgpt.html

[4] The object itself was likely fabricated in Japan in the 1810s–1820s, a composite of a monkey’s torso and a fish’s tail sold to a British sea captain. Barnum leased it from Moses Kimball of Boston’s Museum and displayed it at his American Museum on Broadway in August 1842.

[5] John Barth, Where Three Roads Meet, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2005, 80.

[6] Tiffany Hsu, “A.I. Is Making Death Threats Way More Realistic,” The New York Times, October 31, 2025, www.nytimes.com/2025/10/31/business/media/artificial-intelligence-death-threats.html

[7] This illusion of intelligence is known as the Eliza Effect, named for a 1966 chatbot whose creator was shocked when people formed emotional bonds with a simple script. Decades later, the phenomenon is global.

[8] Pablo Picasso, “Picasso Speaks,” interview by Marius de Zayas, The Arts: An Illustrated Monthly Magazine Covering All Phases of Ancient and Modern Art 3, no. 5 (May 1923), 315–26.