Return to series table of contents

Return to VJIC table of contents

Please note I wish to thank Susanne Baumgartner and Michael Amrose for use of their images in this essay.

| In the second essay I unpacked some of the discourse on street photography. This, the third essay/thread, I focus mainly on the narrative termed as “Fishing and Hunting” to better frame the practice. |

Continuing with my inquiry into “Street Photography” there are two terms that tend to be repeated in various mediated texts: hunting and fishing. The two terms and the references they carry with them act as guiding posts or framework for “street photographers”. They impact how a photographer thinks about what she is doing.

|

|

|

|

All images © Michael Amrose

Before I focus on those two terms, I want to go back and ask the question concerning “street photography” and “photographing on the street”. Is there a difference? The work of Michael Amrose (introduced in essay 2 and above) is a point to note. Amrose photographed markings or patterns found on the street (actually completed street repairs). He was on the street making images, but can he be considered a “street photographer making street photographs”? This may be an obvious point but I feel its implications on how we think about street photography and the practice of image-makers, frame an identity and understanding of a practice. It is important to reflect on the narratives and discourses on photography and photographers as they construct, through repetition an understanding, an identity, of both the image maker and the image viewer.

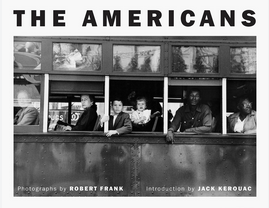

A photographer occasionally mentioned as a street photographer is Robert Frank. Frank was a Swiss photographer and filmmaker best know for his critique of America in the 1950s (post-WWII) through his book “The Americans” (1958). Most informed circles would not have considered Frank as a street photographer, but as an informed observer and critic of American post-war culture and society. Frank was an outsider “looking in”, he was part of the 1950s “beat” culture which rejected aspects of the American culture. Robert Frank provided Americans with a mirror for those who dared to look.

Robert Frank, Book cover

I believe one basic question that defines and determines the practice of proclaimed street photographers is being “on the street” photographing the same as “street photography”? For those who say it does not matter, it does matter to the point of self-identification, practice and critique. Photographing “on” the street produces a set or series of photographs that inquires into a concept or situation. Not a documentary but a unified inquiry, itself a statement.

Fishing and Hunting: a metaphor

First a few YouTube videos on the topic to set the tone. Listen to the dialog, notice the scene or location (selected by the photographer) and consider the stated assumptions concerning practice.

www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hp75HXY-an4

www.youtube.com/watch?v=_Ay5sjTaHpM&t=12s

“Fishing” is understood in the context of what fishermen do, and “hunting” in what hunters do. Both terms carry their own assumptions and narratives and ways of being in the world, let alone making images. This fragmentation of practice, of identity, seems on the surface somewhat obvious, in practice both are complex and layered with assumptions. Assumptions which guide practice, results and judgements.

Fishing

Generally, what fisherman do is fish at locations by a river or a lake that promises to be fruitful, or has the potential of providing a “catch” worth keeping (catch being a fish). Noteworthy, before a fisherman leaves her nest she decides on equipment to bring and carry. The decision on what to bring will dictate how, where and for what she will fish for. For photographers, it determines where and what you may photograph. Briefly, when you go fishing you gather your fishing pole and other items, find your spot at a particular time in the day, place your hook and bait in the water and wait for that moment. Once you get a “nibble on your line” you have to work the fish to catch it and bring it in. There are days that you do not catch what you want and you throw the caught fish back into the water. This is the life of a fisherman and a photographer.

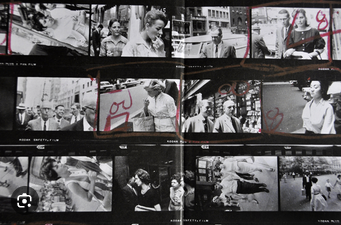

Google search 19 February 2025, Gary Winogrand contact sheet

Fishing and photography do have similar practices constructed within different narratives. To borrow from my text above, the photographer goes to a location where she thinks she can produce the best results at a particular time of day — catch the fish/make an image. The conditions must be right for the hopeful results (an idea that I will return to later) as the ever ready photographer, f-stops set, pre-focused and ready to catch or capture. The images that do not meet the expectations are eventually delated or over-looked through a sequence of editing periods. Images not meeting the expectations of the photographer are returned to river to wait for another day and another fisherman. Expectations as used here is interesting to consider. How and expectations are set even before the photographer leaves door. I want to suggest that expectations emerge and are rooted in the narratives experienced defining photography.

Hunting

© Susanne Baumgartner

Hunting in the context of street photography stirs the imagination; images and concepts related to the “hunt”. To hunt something, idea or object, is to pursue a preconceived goal or in this case an image. How else will a photographer know where and when to look. Experienced hunters understand their target, their prey. The prey is something hunted, a perceived or pre-visualized result, the trophy on the wall. For example, a photographer will place herself in a particular spot or place, the time of day is critical for the light or lack of it may determine the perceived quality or results. This is not a spontaneous decision but well researched, thought out and planned.

A photographer will consider various criteria when getting ready for the hunt. not only will she select a camera (there is a difference between hunting with a 35 mm, a 4×5 view camera or your camera with a phone), a lens(s) and other camera paraphernalia. What you bring on the hunt will define and effect how you hunt, what you hunt and where you hunt. (I imagine that knights facing a dragon carried a huge sword and not a pocket knife) Other considerations that the hunter considers is appearance, how one looks. As some YouTube guides suggest, you want to fit in and not stand out or be noticed. For example, taking a 35 mm camera with a long telephoto lens to the beach will possibly cause one reaction compared to photographing with a Kodak 124 Instamatic. (image: https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Instamatic, 13 July 2024). Camera format will determine how you hunt and what you are able to hunt. Consider wearing camouflage as a way of not being seen, (a note: camouflage emerges out of gestalt perception theory and is used in war and the hunt) or being so obnoxious that you can. not be missed.

Another consideration is knowledge. What do you know about what you want and where to get it. Deer hunters will research where and when deers come to a particular location, that is where they wait for their prey. If you are on the street you need to understand the street and all of its components, in short you need to be “street wise” and blend in, as a warrior or hunter is camouflaged. Depending upon your hunt you need to be accepted in the crowd, maybe become a familiar face. As hunters learned to be “down wind” or to wear animal skins to hide their scent, so must the photographer. Knowledge is an important element of any hunt, how else do you know what to look for. If your hunt is about colors, shadows and light, movement in a space, or social or political statement, the hunter needs to know where and when to be.

© Susanne Baumgartner

The street photographer as hunter is continually looking, searching and reacting. Looking, searching and reacting to what? This is where I believe it becomes interesting. Photographers are provided with many examples of what some will call “good photographs or images” (without defining the term). In many cases, these images become embedded within their consciousness and steer their hunts. As one YouTub mentor suggests, have your camera ready, be pre-focused, set your f/stop for a good depth of field, keep your eyes open and when you see “it” shoot. Always be ready for when opportunity arrives. Street photography festivals and online competitions who award prizes, identify winners and losers, feed into this notion of what is good, ok or bad. What we see are trophies on the wall, we see “it”. “It”, the moment caught, turning the subject into an object, an object to be valued.

Returning to the definitions offered in various videos and essays. The terms/phrases that keep appearing in various definitions include “unmediated chance encounters”, “random incidents in public spaces”, “the moment”, “story telling”, “capturing the moment”, “ordinary or extraordinary”, “not random shooting” but “connecting to the world”. These terms not only begin to define the paradigm of street photography but the photographer herself.

The Photographer

© Susanne Baumgartner

Central to an understanding of street photography is the photographer. To understand photography the photographer needs to be understood. This is of critical importance, for she makes the photos we see, or does she? It is not new or insightful to recognize the individual as constructed through their social, cultural and economic history. We see the world through various lens, seeing and understanding different worlds. Images are the result of a psychological framework that is defined through a life history, through models of expectation and various ideological constructs that define the individual in relationship to a perceived world. How we interact with the world is complex and complicated, there are many factors that come into play. It is not simply entering a public space, capturing 1/125 of a second and then moving on. By framing the space the photographer is abstracting the subject, making it an object to be consumed by viewers. The space is no longer a “continuous space”, but a new space created by the lens, frames and the mind of the photographer. It is through a flow of decisions, conscious or not, that she “captures the moment”. (the term capture is important here)

Vivian Maier, Google search result 2-29-2025, https://zero.eu/

From one perspective, did she have any other choice? Looking at a photographer’s work over a period of time, we can learn how the photographer interacts with the world and the images made reflect their social culture mindset and possibly challenges the expectations of viewers. To do one is to repeat a formula (a cliché), the other to challenge the status quo. This becomes a cultural semiotic inquiry into the creation of meaning. (a topic looked at in the 4th essay)

Whether you are capturing the moment, having chance

encounters or connecting to the world, photography is

concerned with constructing meaning.

There is a narrative relating street photography to “story telling”, stories about the street, society and the photographer. If street photography is approached as “story telling”, then the photographer is the story teller and the viewer the reader. This position assumes that the photographer knows about the street and street life, they have done their homework and the viewer is able to “decode” or read the image, not to reproduce the story but to create their own story.The question I wish to consider is “can a photographer through a photograph or group of photographs tell a story, or is it the viewer’s connection to the images that tells the story?” Is it possible for a single photograph to tell a story? Is it possible for a group of images (sometimes called a project) to tell a story? Whose story would it be? Do we see the story as a reflection of the photographer, her cultural and economic framework in conjunction with her political stance. This is usually termed a “bias”. In photojournalism the photographer is assumed to be neutral and just record the events. How the event is recorded, how they are framed at the moment the button is pushed, where she is standing, what images are selected (who does the editing based upon what criteria) and who is the perceived audience? All these questions play a role in defining the presumed factual and authoritative positioning of the image, the photographer and the viewer. In this way photographs we see are not neutral but subjective, biased if you will. I hold the position that there is no objectivity only subjectivity. Natural science claims through its process to be neutral. That is not possible, they can only limit various variables, an event that is subjective.

Another element in many definitions and narratives is the notion of “unmediated chance encounters”. I am not sure what is meant by that. Since the photographer places herself in a location to have encounters, what happens there is not fully by chance. Can we say that the impact of light/dark, colors, movement, gesture, appearance, and the mentality of the image-maker does not mediate what is seen? What is seen, what attracts your attention is a form of mediation by the photographer herself. It is the same when considering the nature of the camera lens, film or digital (using a film camera limits the number of “shots” one can take, thus mediates the experience), and the camera itself (35mm to twin lens — Vivian Maier used a twin lens camera with 12 or 24 expousers).

When considering narratives, the definitions found

on the web, the deconstruction of the text re-frames

the assumptions defining the practice.

In this short essay I attempted to address issues emerging from definitions which guide or steer the street photographer. My goal was to move the reader of my text to reflect on what impacts their thinking about street photography and photography in general. We need to understand that all images are constructed “texts” to be read.

The next essay will continue in this fashion.