Return to Theme table of content

Return to VJIC table of content

The Making and Breaking of Image

© Alexandra Guerman

Alexandra Guerman is a Sydney-based researcher and curator. Alexandra has a Master of Curating and Cultural Leadership University of NSW. Her research interests include critique and methodology of post-Socialism; postmodernism, postcolonialism, as well as global art and global art history.

Introduction

The initial conversations with VASA presented a unique opportunity to speak to an international audience on the topic of Australian photography. There could have been many ways to approach this broad subject, but to me personally, it felt fitting to introduce the voice of First Nations artists and their unique perspectives as rightful owners of this land. I believe, knowledge and understanding of Indigenous contemporary art, with decolonial and sovereignty focus, outside of Australia is very limited. Therefore, I chose to present contemporary artists that address Australian history and the ongoing effect of colonialism, using both personal and political approach. In the following entries I will be discussing works by Brenda L. Croft, Archie Moore and Daniel Boyd, who use historical archives to interrogate postcolonial discourses. By changing the context of already existing photographs, these artists fundamentally alter the purpose and meaning of these images.

In order to appreciate the meaning of contemporary works and the changed context it is important to understand the original intent of the archival images. To do that, this journal theme will start at the beginning of colonisation period in Australia, presenting long established myths together with more recent discoveries of hidden facts. The archives made by colonial ethnographers at the beginning of twentieth century, the time when overwhelming consensus was that Aboriginal people of Australia were a dying race, and photography was one way of preserving and documenting their image before the inevitable extinction.

Throughout the threads I will be using terms such as First Nations people, Indigenous people and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people inter-changeably to refer to original owners of this land. In saying that, there are over 500 different Aboriginal nations in Australia, each with their own distinctive name, language and territory.[i]

Note: Additional information about some of the images can be found at the end of this essay (Image Notes). Images have been minimally adjusted to facilitate online viewing but have not been overtly edited from their source.

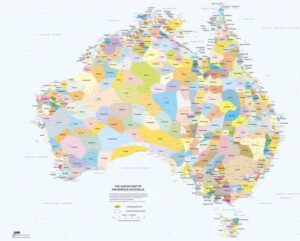

1.2 Image of Indigenous Australia Map, Courtesy of The Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies David R Horton (creator), AIATSIS, 1996. Caption: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australia is made up of many different and distinct groups, each with their own culture, customs, language and laws. They are the world’s oldest surviving culture; cultures that continue to be expressed in dynamic and contemporary ways.

When people who are not familiar with Australia and its politics get asked about this country, the conversation is often skewed towards the description of its people as white anglicized nation of very athletic yet laid back larrikins. It is often coupled with images of vast empty spaces as well as flora and fauna that is out to get you at every possible turn. It is also perceived as multicultural society that prides itself on welcoming people from all walks of life. However, not many can explain the reason why the images of white Australians spring to mind so readily. One can argue, it is due to 70 plus years of “White Australia” immigration policy, which was aimed to forbid people of non-European ethnic origin from immigrating to Australia.

The other reason lies in the hidden away, and the dispossessed original owners of this land that were considered by the colonising governments to be only equal to flora and fauna until 1967. Since the invasion and white occupation, there has never been a treaty, unlike in other colonial countries such as Canada and New Zealand, nor is there an existence of First Nations voice in Australian constitution. Later this year, Australians will vote in a referendum to decide whether to include Aboriginal people in the constitution of their own country! Aboriginal people are not currently recognised or included in the constitution. The Citizenship Act of 1949 gave all Australians citizenship, but laws of specific Australian states—such as the Wards’ Ordinance, which viewed Aboriginal peoples as wards of the state—superseded these rights.[ii] Only a small fraction of the Aboriginal people were granted voting rights, but these were often linked to whether they had employment, if they were literate and could sign a waiver stating that they wouldn’t teach their children Aboriginal culture or language. In 1962 Australian Parliament gave Aboriginal people the option to vote in federal elections, but it was not until 1984 that they received the same rights as the rest of the Australian citizens under the Commonwealth Electoral Amendment Act 1983.[iii]

The limited information and often misinformation

about First Nations people of Australia is a

direct reflection of internal politics

aided by systemic silence.[iv]

The spread of damaging myths is how this

country became to exist, and some would

argue continues to function to this day.

Alexandra Guerman, Commentary on current

political climate around the Voice to Parliament

vote, Video, 2022, Digital File

Starting with secret instructions to lieutenant James Cook prior to the discovery of Australia, the Terra Nullius doctrine, and later the use of ethnographic photography and the media that further vilified Aboriginal people and justified the unlawful takeover of the continent.

In the “beginning”

The most common belief among Australians and people abroad is that Captain James Cook “discovered” the empty southern land in the 1700s, despite the fact that western, southern, and northern coasts of it were already discovered by the Dutch in 17th century and it became known as New Holland. For many centuries prior to that, the Europeans believed in the existence of a vast land in the Southern hemisphere, which they referred to as ‘Terra Australis Incognito’ or ‘Unknown South Land.’[v] The continent got its official name after Mathew Flinders circumnavigated it in 1803 and used the name ‘Australia’ to describe it on a hand drawn map in 1804, thirty-plus years after the “fabled Southern Land” was first “discovered” by Lieutenant (not Captain) James Cook in 1770. [vi] However, to state that something was discovered is to imply that it didn’t exist, yet we have known for some time now that the people of Northern Territory have traded with Indonesians for hundreds of year prior to coming to contact with Europeans.[vii]

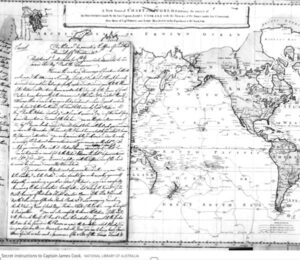

While on board of HMB Endeavour, which was originally commissioned as a scientific mission travelling from England via Tahiti, Cook was equipped with secret instructions from the Royal Admiralty. He was tasked with “charting the content’s coast, obtain information about its people and cultivate friendships and alliances.”[viii] It doesn’t come as a surprise that those instructions were given, seeing as North America was about to gain independence, which resulted in Great Britain losing its penal colony. In 1770, Cook landed in Kamay (Botany Bay) where he spent 8 days and nights replenishing their supplies, collecting plants and trying to interact with the local people.[i

1.4 Image, Secret instructions to Captain James Cook, Courtesy National Library of Australia Caption: James Cook’s famous Endeavour voyage was originally commissioned by the Royal Society of London as a scientific mission. When the Admiralty (Royal Navy) became aware that the Society was planning to commission a sea journey to the Southern Hemisphere to collect scientific data, its members saw an opportunity to become involved. However, their motivations were very different to those of the Royal Society.

The initial interaction proved to be unsuccessful when Cook and his crew were met with resistance from two Dharawal warriors in Kamay, as the British attempted to disembark. Cook’s report of his observations about the native inhabitants of the New South Wales coastline formed the basis for Britain’s decision to establish the colony in 1788. The decision to colonise was further cemented by Joseph Banks, a botanist on Cook’s voyage, who testified before two Houses of Commons Committees, that Botany Bay would be an “advantageous” site for new penal settlement. [x]

Among numerous reasons for his recommendations such as abundance of flora and fauna and fertile soil, the main argument was its “virtual emptiness.”[xi] Cook and Banks saw themselves as pioneers on a mission to collect and catalogue. And even though the legal doctrine of Terra Nullius[xii] was not yet applied in Australia until 1835, the pair most certainly acted as though it was the case. [xiii]

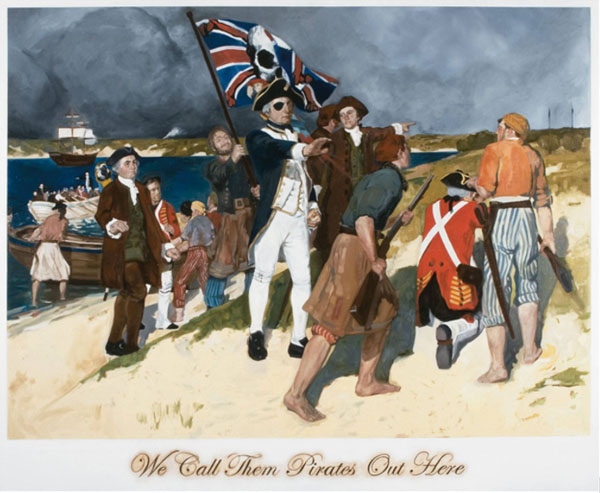

1.5 Painting, Daniel Boyd, We Call Them Pirates Out Here, 2006, Courtesy of Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney Oil on canvas Dimensions 226 x 276 x 3.5cm Caption: “Boyd mocks the official history of white exploration and settlement by suggesting that one person’s explorer is another person’s pirate. This work is a parody of a famous 1902 history painting by Emanuel Phillip Fox depicting the 1770 landing of Captain Cook at Botany Bay.

Of course, most of these “empty” territories were inhabited, so the meaning of Terra Nullius grew to include territories considered “devoid of civilized society.”[xiv]

“Starting in the 17th century, terra nullius denoted a legal concept

allowing a European colonial power to take control of “empty”

territory that none of the other European colonial powers had

claimed.”[xv]

A European reader probably would not see anything wrong with the above statement, “civilized societies” is what we are all about. However, there are some contradicting points that need to be addressed. First, Cook and Banks wrote back to England after having limited interaction with local inhabitants, without any understanding of their customs and traditions, and claimed that the people were few in number, they lived only on the coast and were unlikely to oppose European settlement. In his journal he wrote:

“I do not look upon them to be a warlike People, on the Contrary I think

them a timorous and inoffensive race, no ways inclinable to cruelty, as

appear’d from their behavour to one of our people in Endeavour River

which I have before mentioned. Neither are they very numerous, they live in

small parties along by the Sea Coast, the banks of Lakes, Rivers creeks & Ca.

They seem to have no fix’d habitation but move about from place to place

like wild Beasts in search of food, and I beleive depend wholy upon the success

of the present day for their subsistence.”

In reality, we don’t know how many Aboriginal people occupied the land, but estimates range from a few hundred thousand to over a million. What we do know is that Aboriginal people have settled in every corner of the continent, and their attachment to the land was affirmed through every story of the Dreaming.[xvi] [xvii]

Second point, which seems even stranger, is that the legal doctrine of Terra Nullius was applied in 1835. Forty-seven years after the arrival of First Fleet, headed by Admiral Arthur Phillip, who consequently became the first Governor of NSW colony[xviii]. The First Fleet consisted of eleven ships carrying convicts, navy, soldiers, and free settlers. In these forty-seven years it was well established that the land was heavily inhibited by Indigenous people, not only on the coast but on the interior of the continent.[xix] The settlers had ample amount of time to understand they were not welcome. The initial tolerance towards newcomers wore off, giving way to strong resistance and aggression. It is incredible to think that despite the eradication of 70% of First Nations people due to the outbreak of smallpox, fifteen months after the arrival of First Fleet, they continued to protect their land, and fought brutal wars on all frontiers against the never-ending onset of the settlers.[xx]

In the meantime, in 1823 the American Supreme Court Justice John Marshall has declared in Johnson v McIntosh that the Native Americans were the rightful owners, and the American court did not distinguish between different forms of land use hunting and gathering being amongst them[xxi]. Similarly in our own neighbourhood in New Zealand courts, in the Crown v Symonds case in 1847, Justice HS Chapman remarked that the native title could not be extinguished and the “Māori are entitled to ‘all the enjoyments from the land’ that they had before the arrival of Europeans.”[xxii]

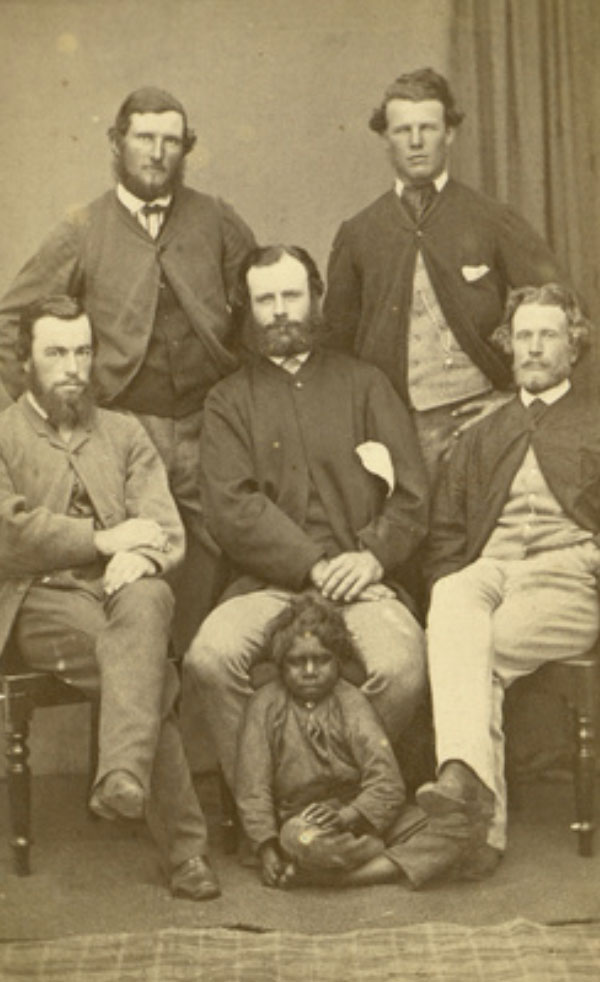

The turn of the nineteenth century marked the transition from the Victorian era of abolition to the rise of human rights movement, with the anti-slavery protest in Britain, which called for changes in the treatment of Aboriginal people.[xxiii] According to the Colonial Office, the Natives were the subjects of the Crown and under its protection. Unfortunately having the protection of the Crown did not amount to much, as the newly self-governing colonial capitals, whose main objective was to expand the pastoral[xxiv] frontiers, did not prioritise the safety of Native people, nor prosecuted the settlers that committed atrocities against them. The pastoralists were encouraged to tame the wild and harsh environments at all costs, in the process securing an enviable reputation in the national folklore as the ‘Aussie battler’.[xxv] For their hard work they rewarded themselves with a piece of ‘black velvet’ wherever and whenever they pleased. [xxvi]

Warning: The following article contains images of Indigenous people now deceased. Their identities are unknown.

1.6 Photograph, Photographer unknown, Thomas Moseley, c1870, State Library, South Australia, Photograph; 9.3 cm x 5.9 cm Five Port Lincoln district pastoralists pose in a group photograph. They are all bearded and wear their jackets buttoned at the top in the style of the day. Seated on the floor in the centre is a small Aboriginal boy, Toby. [On back of photograph] ‘Back row: Thomas Moseley, J.D.Bruce / Front row: William Linklater, J.C. Hamp, Heriot and Toby / Port Lincoln district pastoralists / c. 1870’.

“A pastoralist from the edge of the Nullarbor Plain told a

South Australia Royal Commission in 1899 that he had

known stations ‘where every hand on the place had a

gin, [Aboriginal woman] even down to boys

of 15 years of age’.”[xxvii]

Their often-unsanctioned land grab was overlooked, as the squatters advanced at tremendous speed across vast areas of the continent, killing or driving the local population off their lands and onto settlements for free labour.[xxviii]

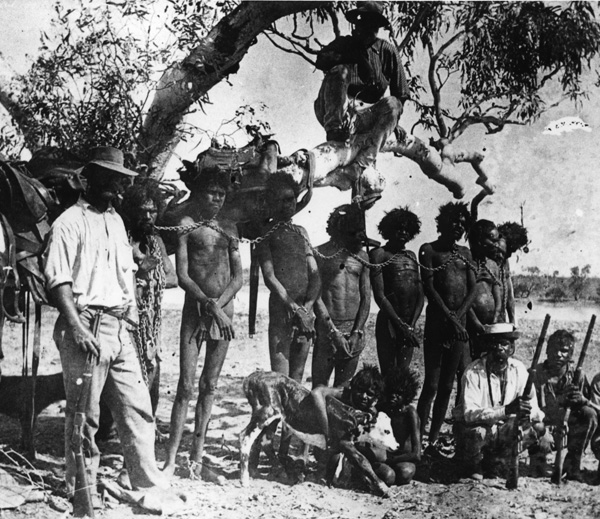

1.7 Photograph, Indigenous Australians in neck chains. Historical records say they had been chained after killing an animal. Neck chains were used by police across Western Australia from the 1880s to the late 1950s. Photograph: State Library

The humanitarian movement together with Anti-Slavery society in London were regarded as annoyance and met with opposition. “It was interference from overseas people who knew nothing about the inescapable realities of colonial life” that stung the most.[xxix]

Alexandra Guerman, Commentary photographic evidence

of cruelty and mistreatment of Aboriginal people in the

media as well as the British parliament, the practice of

neck chaining in Northern Territory and Queensland

continued well in 1950s, Video, 2022, Digital File

Australia continued to uphold Terra Nullius law for another 150 years since its proclamation, in order to justify the illegal occupation of the continent. Its continued existences heavily relied on fabrication of myths that allowed the settlers to be ok with what has transpired. The most common myths were that the Indigenous people were “uncivilised” who didn’t know how to cultivate the land, making it justifiably ripe for the taking. Not staying in the same place long enough, meaning they don’t have ownership. “They were too ‘primitive’ to negotiate with and their ties to their homeland could be totally ignored.”[xxx] And when it became too difficult to continue to disseminate these messages of “simple, childlike people” that need to be controlled, ethnography came to the rescue to further cement the image of the ‘other’.

Endnotes

[i] Aboriginal Peoples, https://www.survivalinternational.org/tribes/aboriginals

[ii] M. Prentis, Concise Companion to Aboriginal History, Rosenberg Publishers, 2011

[iii] Indigenous Australians’ right to vote, National Museum of Australia, https://www.nma.gov.au/defining-moments/resources/indigenous-australians-right-to-vote

[iv] The great Australian silence – In 1968, anthropologist W.E.H. Stanner talked in his Boyer lecture After the Dreaming about the “cult of forgetfulness” practiced on a national scale in Australia, which he termed “the Great Australian Silence”- where Australians do not just fail to acknowledge the atrocities of the past, but choose to not think about them at all, to the point of forgetting that these events ever happened. A different history arose in the Australian memory and it formed negative stereotypes of First Nations peoples. These stereotypes entrenched the ongoing experience of the marginalisation and systematic discrimination of First Nations peoples in Australia.

[v] Where did the name ‘Australia’ come from? National Library of Australia https://www.nla.gov.au/faq/how-was-australia-named

[vi] Secret Instructions to Lieutenant Cook 30 July 1768 (UK) https://www.foundingdocs.gov.au/item-did-34.html

[vii] L. Marks, Did Aboriginal and Asian people trade before European settlement in Darwin? ABC News, 2018, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-01-16/aboriginal-people-asians-trade-before-european-settlement-darwin/9320452

[viii] Australian Museum , Not a discovery voyage, Australian Museum, 2021, https://australian.museum/learn/first-nations/unsettled/recognising-invasions/not-a-discovery-voyage/

[ix] National Museum Australia, Endeavour Voyage, Kamay- Botany Bay, https://www.nma.gov.au/exhibitions/endeavour-voyage/kamay-botany-bay

[x] Botany and Colonisation of Australia 1770 https://www.joseph-banks.org.uk/botany-and-the-colonisation-of-australia-in-1770/

[xi] Ibid

[xii]“The concept of terra nullius became a major issue in Australian politics when, in 1992, during a Aboriginal rights case known as Mabo, the High Court of Australia issued a judgement which some interpreted as an invalidation of terra nullius. The ruling was, however, rather narrower than that. The court did not reclassify Australia as a “conquered” territory but instead restated the terms of Australian sovereignty. The Crown is still deemed capable of lawfully extinguishing native title, but some native title still remains intact where clear indigenous rights can be proved to have existed before the native population was dispossessed. The 1996 Wik Decision went further, stating that native title and pastoral leases could co-exist over the same area; native peoples could use land for hunting and performing sacred ceremonies even without exercising rights of ownership.” Sighted from https://homepages.gac.edu/~lwren/AmericanIdentititesArt%20folder/AmericanIdentititesArt/Terra%20Nullius.html

[xiii] Botany and Colonisation of Australia 1770

[xiv] Terra Nullius, https://homepages.gac.edu/~lwren/AmericanIdentititesArt%20folder/AmericanIdentititesArt/Terra%20Nullius.html

[xv] Ibid.

[xvi] Encounters, National Museum of Australia, Stories of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander resistance, survival and reconciliation from the ‘Encounters’ exhibition, movie, 2018, https://www.nma.gov.au/learn/classroom-resources/australian-journey

[xvii] Aborigibal Contemporary, WHAT IS THE DREAMTIME AND DREAMING?

“The Dreamtime is the period in which life was created according to Aboriginal culture. Dreaming is the word used to explain how life came to be; it is the stories and beliefs behind creation. It is called different names in different Aboriginal languages, such as: Ngarranggarni, Tjukula Jukurrpa. In the Dreamtime, the natural world—animals, trees, plants, hills, rocks, waterholes, rivers—were created by spiritual beings/ancestors. The stories of their creation are the basis of Aboriginal lore and culture. And are also what are often painted by Aboriginal artists.” https://www.aboriginalcontemporary.com.au/pages/what-is-the-dreamtime-and-dreaming

[xviii] Exile or opportunity? National Museum of Australia, https://digital-classroom.nma.gov.au/defining-moments/first-fleet-arrives-sydney-cove

[xix] H. Reynolds, Truth-Telling, History, Sovereignty and the Uluru Statement, 2021 NewSouth Publishing

[xx] M. Langton, in The Australian Wars, SBS, film 2021

[xxi] H. Reynolds, Truth-Telling, 2021

[xxii] Ibid.

[xxiii] J. Lyndon, ‘Behold the Tears’: Photography as Colonial Witness in History of Photography vol 34, no 3, August 2010, Taylor & Francis

[xxiv] J. Hoorn, Joseph Lycett: the pastoral landscape in early colonial Australia, NGV, 2014

“When art historians in Australia refer to the pastoral landscape, they often mean landscapes which describe activities associated with farming and with life in the Australian bush”. https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/essay/joseph-lycett-the-pastoral-landscape-in-early-colonial-australia/

[xxv] K. Whitman, THE ‘AUSSIE BATTLER’ AND THE HEGEMONY OF CENTRALISING WORKING-CLASS MASCULINITY IN AUSTRALIA, 2013

“Going back to the convict, the bushman and the Anzac digger, the ‘Aussie battler’ is a figure often evoked in political, social and popular discourse in Australia to signify a hard-working (white, male) person who is trying to eke out a modest existence through honest and often menial work. The working-class Aussie larrikin is seen as a ‘victim’ in these terms in spite of his powerful, (sub)hegemonic form of white masculinity.”

[xxvi] H. Reynolds, With the White People, Penguin 1990

[xxvii] C. Chang, ‘How early Australians treated Aboriginal people’, NZHerald, 2019, https://www.nzherald.co.nz/world/how-early-australians-treated-aboriginal-people/JNYWLQH37W2ENXQE44LASXB7UY/

[xxviii] H. Reynolds, Truth-Telling, 2021

[xxix] Ibid.

[xxx] Ibid.