Return to theme table of content

Return to VJIC table of content

Photography and the Holocaust: Then & Now

Thread # 5

Jewish Photographic Perspectives, Part 3

Henryk Ross: The Łódź Ghetto Photographs

© Robert Hirsch 2022

www.lightresearch.net

VASA Journal on Images and Culture (VJIC), Theme Editor and Writer

For the sake of Zion, I will not be silent, and for the sake of Jerusalem I will not rest, until her righteousness comes out like brilliance, and her salvation burns like a torch.

The Book of Yeshayahu – The Book of Isaiah – Chapter 62

This is the first of two essays exploring the photographic activities of Henryk Ross (1910-1991) who documented living inside the Łódź Ghetto (pronounced “Lawch”) from 1940 to 1944. Officially, Ross worked for the Statistics Department of the ghetto’s Jewish Administration, photographing the ghetto’s Jewish inhabitants for identification cards and for use in Nazi propaganda. When Ross was not engaged in his bureaucratic capacity, he risked his special privileges and his life to photograph the reality of daily ghetto existence. Ross understood the importance of photographically documenting the Nazi’s genocide to repudiate those who would not believe or who would deny the Shoah. Ross’s photographs lay bare the issues regarding leadership, social class, forced labor, starvation, and the obliteration of religious institutions in a controlled environment where death was the aim.

Notes: Additional information about the images can be found at the end of this essay. Images have been minimally adjusted to facilitate online viewing, but have not been overtly edited from their source. There has been confusion over who has made many of the Łódź Ghetto photographs. A number of Ross’s photographs have been attributed to Mendel Grossman although the negatives are in the Ross archive. I believe that possession of negatives is the best method of attribution even though some of Ross’s images survive without the negatives, which is not surprising given the history that follows. Also, bear in mind that Grossman’s images were published posthumously without his input. Regardless of the maker, what is essential is their existence as visual proof of the German extermination of the Łódź Ghetto Jews.

Through the eyes of a few we can see many.

5.1 Attributed to Mendel Grossman. Henryk Ross Photographing Identification Cards for the Jewish Administration, Statics Department, 1940. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada.

Background

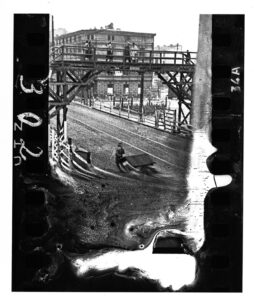

5.2 Henryk Ross. The bridge crossing Zigerska Street, the “Aryan” street that divided the Łódź Ghetto into two areas, 1940. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada.

Henryk Ross was born in Warsaw, Poland in 1910 and died in Israel in 1991. Before World War II he was employed as a press and sports photographer for a newspaper in Łódź. In January, 1940, after Germany’s successful invasion of Poland in 1939, Ross was forced to move into the Nazi’s tightly-sealed ghetto. He was able to get a job as one of the official ghetto photographers.[i] Along with his colleague, Mendel Grossman (see previous essay), Ross made resident identity and promotional photographs for the Department of Statistics in the Łódź Ghetto. These marketing images showcased Jewish slave labor productivity, such as in the ghetto’s mattress and leather factories, in hopes of showing the Germans the value of not slaughtering them. Both these activities made Ross a member of the Nazi’s Judenrat/Jewish Council.[ii] Ross later testified: “Those who worked received an extra ration of soup.”[iii]

5.3 Henryk Ross. Seamstresses making mattress to display the value of Jewish industry within the ghetto, 1941-1944. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada.

5.4 Henryk Ross. Children Being Deported to Chelmno nad Nerem Extermination Camp, 1942. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada.

This practice, in which members of the Jewish community operate as liaisons between the Jews and the Germans, dates back to the Middle Ages and is often condemned by other Jews. However, this position gave Ross access to a camera, film, and processing facilities, which was vital as the Germans made it illegal for Jews to own a camera.[iv] Hiding his camera underneath his coat, Ross would slightly open and release the shutter while his wife, Stefania, acted as a lookout.

5.5 Henryk Ross. Excavating the box of more than 6000 negatives and documents buried by at 12 Jagielonska Street in the Łódź ghetto, 1945. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada.

When the liquidation of the ghetto began in 1944, Ross and Stefania were ordered to stay behind to clean-up the crime scene and they buried his collection of 35mm cellulose nitrate negatives, prints, and other ghetto records in sealed iron jars that were then placed in a wooden box lined with tar. Both endured and after the liberation of the ghetto by the Russian Red Army, they dug up the intombed materials only to discover that groundwater had caused half of his 6000 negatives to be ruined or damaged. The decomposition to Ross’s surviving negatives, made on highly flammable nitrate-based film, converted them from literal depictions into uncanny, haunted, poetic expressions of moral anguish. This unintentional physical destruction became a striking visceral metaphor of the overwhelming loss of humanity suffered by the Jewish ghetto slaves. Symbolically it allows the images to achieve a spiritual transcendence from the ghetto world that was outwardly defined by alienation, anxiety, mortality, and nullity. Philosophically, this points out how a narrative about reality can be progressively constructed in highly complex ways that can fluctuate over time.[v]

Circumstances of the Photographs

Ross’s official photographic job gave him special benefits not afforded to others as long as he was useful to the Germans. There was a vast incongruity between the ghetto elite, those who had skills the Germans found useful, and the rest of the captives. The social structure of the ghetto was similar to pre-ghetto life based on family history, connections, education, and wealth, which determined one’s societal position. There were still the haves and the have nots. Most residents had no running water or sanitation and faced starvation and overcrowding. Ghetto existence was extremely brutal and traumatic for all—everyone was in it together as being Jewish has never been a neutral subject. All Jews, from babies to scarecrows, had to wear a yellow star “Jew badge,” which derived from medieval times, when both Christians and Muslims decreed that Jews must wear articles of clothing that would set them apart and shame them for being different. The Germans took this to the next level, making Hitlerism a national religion that declared Jews to be a separate, dangerous, subhuman, zoomorphic race responsible for all the world’s woes, that required total extermination.

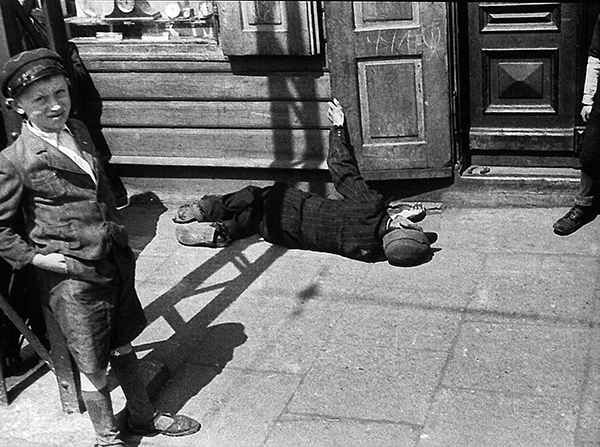

5.6 Henryk Ross. Boy falling in the street from hunger, 1940-1944. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada.

Both the Germans and the Jewish Council banned photography for private purposes.[vi] Nevertheless, Ross used his Privilege to clandestinely make photographs that juxtaposed daily subsisting with those of people dying in the street of starvation, along with the on-going deportation of children, the elderly, and the infirm. Eventually, all the deportees, including Mordechai Chaim Rumkowski (a.k.a. ‘King of the Ghetto’) who was the head of the Nazi’s Judenrat/Jewish Council, were exterminated.[vii] It is likely Rumkowski

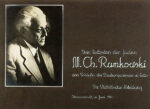

5.7 Henryk Ross. Inside page from the Annual Report with a dedication from Mordechai Chaim Rumkowski, head of the Łódź ghetto’s Judenrat Administration’s Statistics department, 1941. Yad Vashem Archive, Jerusalem, Israel.

was slain by fellow Jews upon his arrival at Auschwitz, who considered him a traitor.[viii] After liberation by the Russian army, many viewed Ross’s behavior as a form of collaboration similar to that of Rumkowski’s policy of ‘Rescue through Work,’ which supplied goods to the Germans from over 120 ghetto factories. This raises the issue: Did Ross’s actions of disobeying the prohibition on taking pictures that were not officially approved make him a Kapo (collaborator), a survivor, a documentarian, a resistance fighter, or all of the above?[ix]

Rumkowski wrote to Mendel Grossman, making clear the official policy on personal photography: “I hereby notify you that you are forbidden to engage in your profession for private purposes, and that you must immediately liquidate your business. Your photographic work will be limited from now onward to the department in which you work. All other photography activities are strictly forbidden.”[x]

Jewish Łódź Ghetto Life

Like Mendel Grossman’s images, Ross’s photographs depict familiar scenes of hunger, despair, and death; 20 percent of the ghetto inhabitants died of starvation. Of the over 200,000 people who passed through the Łódź ghetto’s 2.4 square kilometers, less than 900 remained. Ross photographed ghetto workhands who had to go barefoot while pushing the fecal carts – a horrible and dangerous job that often led to death by typhus and reduced them to draft animals. He photographed scenes of misery near the ghetto prison, public hangings, and the deportations of the Łódź Jews to their deaths at Chelmno. Chelmno was the first Nazi extermination camp that initially eradicated people in gaswagens, trucks reequipped as mobile gas chambers, until gas chambers were developed as a more efficient method for killing larger numbers of people.[xi] Ross chronicled people writing their last notes to their families, and children waiting behind chain-link fences to be taken to unknown destinations during the “Sperre,” the deportation in September 1942 in which most children under ten years old, the elderly, and sick who had no “labor value” were deported and exterminated as if they were lethal parasites that threatened humankind.

People either swelled up from hunger or became emaciated.

There were cases of people collapsing in the street;

there were cases where they collapsed at work and at home

because of the difficult conditions. We were six to eight persons

to one room, depending on the size of the room. People froze from

the cold. There was no heating. … I saw entire families, skeletons of

people, who during the night were dying with their children.[xii]

5.8 Henryk Ross. Fecal Worker in torn clothes wearing only one boot, 1942-1943. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada.

However, his collection also includes photographs that appear mind boggling in the context of traditional Holocaust representation. Ross saw the beauty among the suffering that the ghetto population faced on a daily basis. He photographed scenes such as birthday parties, children playing, and a couple kissing; without context, the subjects seem to be leading an ordinary life. Knowing that these pictures were taken in the midst of annihilation, humiliation, and starvation can initially seem perplexing. However, in hindsight, we can understand the ghetto inmates’ attempt at some semblance of normal life as a form of defiance.

5.9 Henryk Ross. Young Girl Smiling, 1940-1944. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada.

One should consider how Ross made use of his “special license.”[xiii] Ghetto life was fundamentally about the here and now, surviving the day, as not much thought was given to having a future. Ross was able to envision a future, even without himself, and this was a motivating force to act as an insurgent against German tyranny. Ross didn’t have a gun, rather he used the tool he knew how to operate and had access to – a camera – a picturemaking device designed to stop and record time in the present for the future generations to ponder.

Unlike today, few people had the means to make, process, and distribute their photographs, which were likely made with a simple Kodak-like box camera. Ross used black-and-white film, often Agfa Isopan F with an ISO of 40, which was much less sensitive to light than similar contemporary films that have an ISO of 400. Most images appear to be handheld exposures made with available light. Interior scenes would have required long exposure times, possibility up to a few seconds, which introduces camera shake and explains why the results are often not sharp. In those pre-digital times, the darkroom was a mysterious place, where, under the glow of a safelight, a combination of skill, equipment, and supplies allowed a picture to magically appear. Also, it was an era when people generally posed for the camera, if they were aware of its presence, making the act of taking a photograph a cooperative event, captured with a single exposure of film. Collectively, Ross’s archive also shows us a remarkable sense of determination and resilience – a affidavit to endurance – making his photographs an act of resistance. This was also a mental feat as dealing his own daily existential angst and chronic sense of impermanence required non-stop psychological juggling as everything was constantly something other than what it just was. In such a mindset, Ross’s camera offered a physical anchor, a purpose, in his homicidal surroundings. Each frame of film can be considered an attempt to stabilize the constantly shifting lack of certainty he had to negotiate to stay alive in an environment of unchecked power.

Having an official camera, I was able to capture all the

tragic period in the Łódź Ghetto… I did it knowing

that if I were caught my family and I would

be tortured and killed.[xiv]

To be continued….

5.10 Henryk Ross. Couple Kissing, 1940—1944. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada.

Afterword

As this essay was being prepared for publication, a white, teenage gunman from the Binghamton New York area drove to Buffalo New York (where I live) and opened fire at a grocery store in a predominately Black neighborhood, killing ten innocent people and wounding three (eleven were Black and two were white).[xv] Apparently radicalized online, the murderer live-streamed his homicidal spree and left a rambling manifesto citing the fraudulent, antisemitic “Great Replacement” as a motivating force for murdering Black people. This horrendous belief resurfaced to public attention in 2017 when about 500 white supremacists, marching in Charlottesville, Virginia, deplorably chanted: “Jews will not replace us.”[xvi] In essence, this counterfeit ideology claims there is an intentional effort, led by Jews, to promote mass immigration, intermarriage, and other efforts that would lead to the “extinction of whites.” In his manifesto explaining the attack, the Buffalo shooting suspect blamed Jews for pushing out whites and accused “Jewish puppeteers” of believing they are superior because they call themselves “God’s chosen people.” “Why attack immigrants when the Jews are the issue?” the suspect asks rhetorically. His answer: “They can be dealt with in time.” He continues: “For our self-preservation, the Jews must be removed from our Western civilizations, in any way possible.”

This eerily echoes what happened in 2018 at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh, PA where a white gunman, who claimed the Holocaust was a hoax and espoused contempt for a nonprofit Jewish group that helped refugees, yelled “All Jews must die,” then opened fire upon the congregants. He was armed with an assault rifle and several handguns and killed eleven congregants and wounded six others, four of whom are police officers. Upon surrendering, the suspect told a police officer that he “wanted all Jews to die” because Jews “were committing genocide against his people.”[xvii] These horrific actions act as reminders that what starts with the Jews does not end with the Jews. In Germany it did not take long for people who were burning books to start burning people. This form of Othering, marginalizing groups of people who are imagined to be intrinsically alien to one’s group and therefore incapable of conforming to their groups social norms, precipitated the Armenian genocide, the Shoah, the Cambodian genocide, the slaughter in Rwanda, and Andre Mackneil, a Black grocery shopper in Buffalo, who went to buy a surprise birthday cake for his three year old son and never returned home.[xviii]

5.11 © Sharon Cantillon. Children Writing on Memorial Wall, May 20, 2022. The Buffalo News.

5.12 Their New Jerusalem, 1892. Judge magazine.

5.13 © The Tree of Life Synagogue Street Memorial, 2018. SOPA Images/Light Rocket.

5.14 Andre Mackneil, 2022. Facebook.

Shiva Call

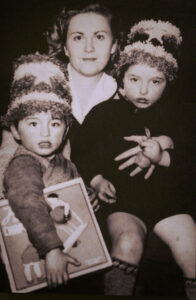

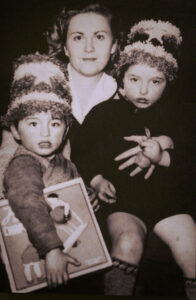

5.15 Unknown photographer. Andrée Geulen with two of the 300 or so Jewish children she rescued in Nazi-occupied Belgium.

A shiva call (condolence call) is a vital component of Jewish funeral customs for both the mourner and their community. Shiva is a seven-day mourning period that begins immediately after the funeral concludes. The word shiva means ‘seven’ and signifies that the mourner will grieve for a specific seven-day period. During this period family, friends, and co-workers offer their sympathy and comfort, which is considered a Mitzvah (a good deed).

Andrée Geulen, Savior of Jewish Children in Wartime, Dies at 100. A Belgian teacher, who kept Jewish children from falling into the hands of Nazis, hiding them in convents, monasteries, and farms. After the war, she reunited many with their parents. See: Joseph Berger, “Savior of Jewish Children in Wartime, Dies at 100”, June 7, 2022, www.nytimes.com/2022/06/07/world/europe/andree-geulen-dead.html

5.16 . © David Silverman. Andrée Geulen-Herscovici is embraced by Henri Lederhandler, one of the children she rescued, in front of the exhibit on her efforts in the museum of the Yad Vashem Holocaust Memorial in Jerusalem, April 18, 2007.

Acknowledgements

This is an ongoing project and subject to revision as it progresses.

Feedback and suggestions are welcome.

Research assistance by Ruby Merritt.

Special thanks to Lisa Murray-Roselli for her editing expertise.

This theme is supported by the following organizations and individuals:

VASA, Vienna, Austria: Roberto Muffoletto, Director

CEPA Gallery, Buffalo, NY USA: Véronique Côté, Executive Director & Chief Curator

Galicia Jewish Museum, Kraków, Poland: Tomasz Strug, Deputy Director and Chief Curator

Jewish Community Center of Greater Buffalo, Buffalo, NY USA: Katie Wzontek, Cultural Arts Director

Endnotes

[i] German forces occupied the vibrant, textile city of Łódź on September 8, 1939. The Nazis contemptuously rounded up more than 160,000 Jews and Roma and confined them to a poor industrial section of the city. Here they lived and worked behind barbed wire while surrounded by armed sentries in what was a 1.6-square-mile prison. Of the over 1,000 ghettos created by the Nazis to segregate Jewish populations in cities across Eastern Europe, only the one in Warsaw was bigger than Łódź.

[ii] Judenrat (in plural, Judenraete), were Jewish councils set up within the Jewish communities of Nazi-occupied Europe on German orders. The Judenraete was charged with implementing the Nazis’ policies. These Jewish councils often attempted to perform an unachievable balancing act: on one hand, trying to help their fellow inmates, on the other, they were burdened with carrying out Nazi orders that deprived their fellow Jews of their livelihood, their health, and eventually their lives. The Germans delegated the distribution of food rations to the Council. Those willing and able to work received higher rations. This meant that average prisoners could increase their chances of subsisting by working for the Germans, thus forcing them to decide whether to “collaborate” or be deported.

[iii] Greg Cook. “How Henryk Ross Risked His Life To Secretly Photograph Life In A Nazi Ghetto,” WBUR, March 29, 2017. www.wbur.org/news/2017/03/29/henryk-ross-nazi-ghetto

[iv] The Nazis recognized the power of photography to shape public opinion. They banned Jews from working in the film industry both in front and behind the camera so they could control the media narrative. The big Hollywood studios, desperate to protect German business, let Nazis censor scripts, remove credits from Jews, get movies stopped and even force one MGM executive to divorce his Jewish wife. See: www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/general-news/how-hollywood-helped-hitler-595684/

[v] The complicated and stressful circumstances surrounding Ross’s collection and its fresh interpretation can be seen in CEPA Gallery’s Wild Things: Disrupting the Photographic Archive in the Time of a Pandemic. The exhibition’s premise is how photographs are understood over time is slippery and dependent upon place, and the background of each viewer. This 2020 group exhibition and catalog included facsimile prints of Ross’s work. See: www.cepagallery.org/exhibit-event/wild-things-2020/

[vi] On December 8, 1941, Mordechai Chaim Rumkowski, the leader of the Łódź Jewish Council, wrote to Mendel Grossman, making clear the official policy on personal photography: “I hereby notify you that you are forbidden to engage in your profession for private purposes., and that you must immediately liquidate your business. Your photographic work will be limited from now onward to the department in which you work. All other photography activities are strictly forbidden.” Copy of this letter in: Viviana Uria, et al. Flashes of Memory: Photography During the Holocaust (Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 2018), 134.

[vii] Under the contentious leadership of Mordechai Chaim Rumkowski, chairman of the Jewish Council of the Łódź Ghetto, the ghetto was turned into a series of workshops. Rumkowski, who had been an unsuccessful businessman and an orphanage director, believed that if the ghetto provided goods for the Nazi war effort, its residents would be safe and deportations to extermination camps could be avoided. Nevertheless, the Council drew up the lists of those who were deported via vans and cattle cars to death camps in Chelmno nad Nerem and Auschwitz-Birkenau, often exempting those connected with the Council’s functions. However, this was done under the German threat of liquidating the entire ghetto. The Łódź ghetto existed longer than any other Polish ghetto and had the highest survival rate. Had the Russians advanced faster in 1944 many more lives would have been saved. The Council also made an archive of what was actually happening in the ghetto. In the end, regardless of their decisions or position, the Germans murdered 95% of the ghetto inhabitants. The role played by Judenraete continues to be extremely controversial.

[viii] In August 1944, Rumkowski and his family boarded the last transport to Auschwitz and were murdered there on August 28, 1944, by the Jewish Sonderkommando inmates who beat him to death as revenge for his role in the Holocaust. This account is confirmed by witness testimonies of the Frankfurt Auschwitz trials. See: “Chaim Mordechai Rumkowski,” Jewish Virtual Library, www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/chaim-mordechai-rumkowski

[ix] Konrad Kwiet. “Kapos: Collaborators, Perpetrators or Victims?” See: https://sydneyjewishmuseum.com.au/news/kapos/

[x] Copy of the letter in Viviana Uria, et al. Flashes of Memory: Photography During the Holocaust (Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 2018), 134.

[xi] In August 1941, SS chief Heinrich Himmler watched a mass-shooting of Jews in Minsk that was arranged by racist, mass executioner Arthur Nebe, after which he vomited. This led the weak stomach Himmler to decide that alternative methods of killing needed to be used. See: Peter Longerich. Heinrich Himmler: A Life, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012). 547.

[xii] Ross describing their starvation. See: Greg Cook. “How Henryk Ross Risked His Life To Secretly Photograph Life In A Nazi Ghetto,” WBUR, March 29, 2017. www.wbur.org/news/2017/03/29/henryk-ross-nazi-ghetto

[xiii] See: “The Photographer’s Special License” in Robert Hirsch, Exploring Color Photography: From Film to Pixels (London & New York: Focal Press, 2015), 118.

[xiv] Henryk Ross, statement, Art Gallery of Ontario, 1987 in: Vivian Uria, et al, Flashes of Memory: Photography During the Holocaust (Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 2018), 141.

[xv] “Complete coverage: 10 killed, 3 wounded in mass shooting at Buffalo supermarket,” https://buffalonews.com/news/local/complete-coverage-10-killed-3-wounded-in-mass-shooting-at-buffalo-supermarket/collection_e8c7df32-d402-11ec-9ebc-e39ca6890844.html#tracking-source=article-related-bottom

[xvi] Jonathan Sarna. “The Long, Ugly Antisemitic History of ‘Jews Will Not Replace Us,’” Nov. 19, 2021, www.brandeis.edu/jewish-experience/jewish-america/2021/november/replacement-antisemitism-sarna.html

[xvii] “Pittsburgh synagogue shooting,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pittsburgh_synagogue_shooting

[xviii] Joshua Rhett Miller and Steven Vago. “Buffalo shooting victim was picking up son’s birthday cake,” New York Post, May 16, 2022, https://nypost.com/2022/05/16/buffalo-shooting-victim-andre-mackneil-was-picking-up-cake-family/

Image Captions

5.3 Henryk Ross.

5.3 Henryk Ross. Seamstresses making mattress to display the value of Jewish industry within the ghetto, 1941-1944. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada.

Caption: Seamstresses making mattress covers to demonstrate the value of ghetto slave workshops to the Germans. This was the survival strategy of ‘Work is the Way’ Mordechai Chaim Rumkowski, the head of the Nazi’s Judenrat/Jewish Council, used in hopes of keeping the ghetto as a whole alive even though it meant sacrificing a succession of individual lives.

5.4 Henryk Ross.

5.4 Henryk Ross. Children Being Deported to Chelmno nad Nerem Extermination Camp, 1942. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada.

Caption: Children riding in a horse-drawn wooden carriage, one even smiling for the camera, were among the 20,000 taken from the Łódź Ghetto to the Chelmno nad Nerem extermination camp 30 miles north of the city, which operated from 1941-1945. The weak and vulnerable were the first to be gassed. This included children collected from orphanages and those ripped from their parents, the sick extracted from hospitals, and the elderly pushed out of nursing homes for their lack of labor value.

5.5 Henryk Ross.

5.5 Henryk Ross. Excavating the box of more than 6000 negatives and documents buried by at 12 Jagielonska Street in the Łódź ghetto, 1945. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada.

Caption: Henryk Ross said: “[This print] shows the excavation of the box containing documents and photographs of life in the Łódź Ghetto from 1940 to 1944. The excavation was attended by my wife, Stefania Ross, Zenon Goldreich with his wife, and Jacob Urbach, all of whom were in the Łódź Ghetto. We buried the box with documents and photographs in the ghetto at 12 Jagielonska Street during the final liquidation.

5.6 Henryk Ross.

5.6 Henryk Ross. Boy falling in the street from hunger, 1940-1944. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada.

Caption: One-quarter of the ghetto prisoners died of starvation, which destroys one’s organs and brain function, breaking even the most resilient people. Food rations provided about 360 kcal per day for adults. Generally, the recommended daily calorie intake is 2,000 calories a day for women and 2,500 for men. As desperation set in, people ate carrion, rodents, and what was called “cocoa,” which was actually powdered brick. Symptoms of starvation include: disorientation, hallucinations, convulsions, bloating, and hair loss. Exhaustion becomes overwhelming. One’s feet and legs become limp, the body collapses, and the active dying process begins.

5.9 Henryk Ross.

5.9 Henryk Ross. Young Girl Smiling, 1940-1944. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada.

Caption: The chaotic damage to this negative intensifies the anguish of knowing that this girl, surrounded by flora, never got to have a natural life.

5.11 © Sharon Cantillon.

5.11 Sharon Cantillon. Children Writing on Memorial Wall, May 20, 2022. The Buffalo News.

Caption: There is a memorial in Jefferson Utica Plaza in Buffalo, NY where large photographs of the those slain at their local grocery store are on display. Chalk is available to write thoughts, feelings, and well wishes.

5.12 Their New Jerusalem, 1892. Judge magazine.

5.12 Judge magazine. Their New Jerusalem, 1892.

Caption: This antisemitic Replacement cartoon portrays Jews (on the right) streaming into New York City’s Broadway, turning it into “Their New Jerusalem.” All the Broadway business signs now have Jewish names, such as Cohen, Levy, and Steinberg. Meanwhile, the Americans (on the left) who settled the city are moving to the sunny West. The caption at the bottom of the cartoon reads: “Our first families driven out.”

5.13 © The Tree of Life Synagogue Street Memorial, 2018. SOPA Images/Light Rocket.

5.13 © The Tree of Life Synagogue Street Memorial, 2018. SOPA Images/Light Rocket.

Caption: Federal prosecutors are seeking the death penalty for the alleged shooter, but some of the congregants have objected; believing that capital punishment conflicts with the Jewish faith.

5.14 Andre Mackneil, 2022. Facebook.

5.14 Andre Mackneil, 2022. Facebook.

Caption: Andre Mackniel, 53, was among the10 Black people shot and killed in a Buffalo, NY grocery store when an 18 year old white supremacist went on an absurd lethal rage. “[Andre] never came out with the cake,” said Mackniel’s cousin, Clarissa Alston-McCutcheon, adding that such a kind gift gesture wasn’t uncommon for him. “Just a loving and caring guy. Loved family. Was always there for his family.”

5.15 Unknown photographer.

5.15 Unknown photographer. Andrée Geulen with two of the 300 or so Jewish children she rescued in Nazi-occupied Belgium.

5.16 . © David Silverman.

5.16 . © David Silverman. Andrée Geulen-Herscovici is embraced by Henri Lederhandler, one of the children she rescued, in front of the exhibit on her efforts in the museum of the Yad Vashem Holocaust Memorial in Jerusalem, April 18, 2007.