Return to Series Table of Content

Ione Manzali is a visual artist and researcher in philosophy of art, phenomenology, and zen budism. She has been publishing, lecturing and teaching workshops in Europe, Rio de Janeiro and New York. Her home is Brazil and currently lives in Europe.

Phenomenology of Photography: Walter Benjamin

Benjamin called it a trace of an auratic experience; for Barthes, an unclassifiable thing charged with love feelings and madness; it was for Sontag, a strange object of an elegiac art and for Flusser the marker of the possibility of freedom in a world dominated by self comanded machines. What is this thing, after all, this phenomenon we call photography?

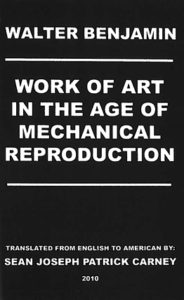

Walter Benjamin’s The work of art in the age of its technological reproducibility.

Walter Benjamin (1892-1940) wrote in 1936 the essay The work of art in the age of it technological reproducibility [Das Kunstwerk im Zeitalter seiner technischen Reproduzierbarkeit]. It was translated to French by Pierre Klossowsk and published later in the same year in Paris. Three more versions of the manuscript followed it and the third version is the one most known and commented. This piece condenses Benjamin’s more mature media theory that followed his enduring interest in Jewish mysticism, in radio, tv, music and cinema besides his expertise in German literature and philosophy. It became a canonical text in media studies and art history.

In 1931 in A short history of photography, Benjamin noted that the best, the prime of photography, epitomized in the works of Julia M. Cameron, Hill, Hugo and Nadar, were made in the first decade of photography’s development. That is, Benjamin notices there is something in the pre industrial photos, a particular something lost in the industrialized stage of photography, an aspect that is not present any more in the large scale reproductions of an image. He called it the “aura“of the original piece of work.

What is an aura of a work of art? In this essay, Benjamin focuses in the lost aura of the work of art but in previous writings this concept embraces other aspects of life: an aura is the essence and uniqueness of an entity, its authenticity. Such authenticity is directly related to the peculiar time and space, the historical situation of a remarkable object. Around the concept of aura, Benjamin investigates the conditions of possibility of any experience [Erfahrung] in modernity. Taking from Ludwig Klages’ distinction between Erfahrung and Erlebnis, Benjamin points to the traditional and communitary link present in a Erfahung as opposed to the momentary and superficial experience as Erlebnis. Precisely, it is the transmitted meaning that an experience [Erfahung] with an original work of art, the one with aura, i.e., historically situated and charged with a determined communitary sense, and also loaded with what he calls authority, i.e., a presence both as an extant meaninful and relational entity, what is replaced by a superficial and purely aesthetic experience [Erlebnis] offered by the mass reproduced images of works of art. In his words, “Even the most perfect reproduction of a work of art is lacking in one element: its presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be” adding, ” that which withers in the age of mechanical reproduction os the aura of the work of art“.

But, again, what is a photography for Benjamin here? It is after the essence of photography the reason Benjamin examines: 1. what kind of experience does photography brings, vis a vis traditional arts such as painting; 2. what changes in perception of reality does this new media leads to; 3. the increasing ubiquity of the visual culture in every day life; 4. how much of a vehicle to the dissemination of a global, international, ahistorical, technological and bland mass culture the serial reproduction of photography disseminates; 5. To what extent does a technologically mediated culture allows for a connection to the culture of our ancestors, a historical and situated culture; 5. what is the meaning of art in an era fascinated with and comanded by technology.

Benjamin develops the thinking on photography on a meditation on art. He points to the effects of the production of ever transportable, adaptable, and displayable to the masses of an art turned into aesthetic object, more and more perfectly reproducible. Anticipating later developments of a society of spetacle, the inevitable culmination of art’s autonomy into art pour l’art, says Benjamin, is how mass culture turns art into entertainment and where it ends up playing a role in a fascistic political way of conducting the anonymous and uprooted masses created by the modern way of life. “The instant the criterion of authenticity ceases to be applicable to artistic production, the total function of art is reversed. Instead of being based on ritual, it begins to be based on another practice: politics.”

The optical unconscious revealed by photography, in a analogy that Benjamin establishes with the psychoanalytical’s theory of the unconscious impulses, will reach, necessarily, its pinnacle with the development of the moving image. For Benjamin predicted that the cinema could be either the great revolutionary art, the art of our time or else the major instrument of mass manipulation by perfecting a controlled virtual reality. And it is in movies and their distracted aperception (one can see the constant distracted connectivity of the internet anticipated here) of the masses that what he calls the fascistic control will exercise its powers (Benjamin tried to mingle his originary mystic interest with marxist materialist dialectics, a failed attempt, of course. Opposing the term “fascism” to what he named “communism” he could not have figured then the worst fascism, the genocides, the hunger and the terror that were growing in communist Russia). The consummation of the fascist l’art pour l’art, the objects of pleasure and entertainment for the masses (by masses here we could include the crowds that today fill museums, Venice and Whitney bienials), says Benjamin, will happen in the next world war as a great spectacle, fiat ars – pereat mundus, the end of one historical world. Factual or cultural death, the dying old world is where art had a certain role, a major role, and the coming new world, that started with middle class’ aestheticism is the one reaching an apex in the legitimation of the increasing visual but artless techno pop culture of the masses, where “the work of art reproduced becomes the work of art designed for reproducibility“.

Rooted in the analysis of the dialectics between art and technology, the essay opens up many doors on several areas, such as mass entertainment, politics, art history, architecture and photography’s history. And for the essence of photography? In this essay, Benjamin says it is up to us, of our awereness of the historical essence of technology, either to be enslaved by it or to make out of it a road to freedom and beauty, that is, to art. With the advent of photography, we see here, the turning point where the possibility of a new horizon where art and technology may reconcile or definitely diverge, opens itself up.

Rooted in the analysis of the dialectics between art and technology, the essay opens up many doors on several areas, such as mass entertainment, politics, art history, architecture and photography’s history. And for the essence of photography? In this essay, Benjamin says it is up to us, of our awereness of the historical essence of technology, either to be enslaved by it or to make out of it a road to freedom and beauty, that is, to art. With the advent of photography, we see here, the turning point where the possibility of a new horizon where art and technology may reconcile or definitely diverge, opens itself up.