Return to VJIC Table of Content | Return to Thread Table of Content

Sándor Szilágyi, PhD, is a Hungarian media theorist, writer on photography, living in Budapest, Hungary. His interest range from Hungarian art photography, documentarist photography, and the theoretical questions of photography.

This is the fifth of ten essays on photography by Sándor Szilágyi. To view Imre Drégely’s photographs, visit http://www.fotografus.hu/en/fotografusok/imre-dregely/80-90s.

© Imre Drégely, Lightning (1988).

Take This, Photoshop!

Imre Drégely is perhaps the most playfully spirited, “smart” Hungarian photographer;

yet his images are not mere interpretations of form for their own sake. Behind his gags there are very serious issues with which he tries to circumscribe the nature of photography as a medium of communication. Behind the mask of a clown is a philosopher.

Interestingly enough, throughout the course of his visual experiments, which he has been conducting for a good fifteen years, Drégely has not stepped beyond the bounds of traditional photography for a single moment. Instead, he attempts to extend the boundaries of chemical-based photography with images that in and of themselves are valid visual statements (being both beautiful and interesting).

Today, it is possible to do much of his experimentation using Photoshop; but then, there would be no point. The works would lose their punch with photography, once again, restricted to the reality of our technological tools.

Elemental magic

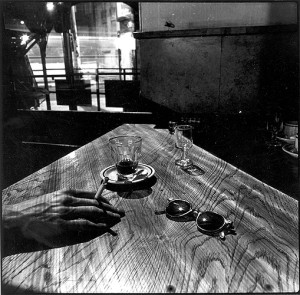

© Imre Drégely, Café (1989)

Take, for example, Café from the series, Budapest at Night (1988-89).1 Using Photoshop, an artist could undoubtedly insert a shadow pattern onto the table and the hand resting on the table, similar to what is evident in Drégely’s work. But then the image would lose its accidentals and its capacity for capturing that which could be seen there and then exactly as it was. In other words, it would lose the magical property of every photograph: its documentary characteristic.

The same can be said of Cats from the Budapest at Night series. At the precise moment that Drégely took this photograph, five cats were there at the entrance to a block of flats, thus imbuing the image with its ambience and metaphysical inspiration. What would be the point of slipping them in later on the monitor? Is it not lamentable if we try to take the job of the Creator?

Of course it is! Imre Drégely knows this well. And that is why he puts on the face of a clown, putting his role as a creator of sights in quotations. While he perfectly understands the magic of the print and its power to conjure up reality, he views his own role as the “magician” with cheerful self-irony. He uses his creative power enthusiastically, almost bubbling with child-like joy while warning, “Look! I’m cheating!” He takes photography dead seriously, but not himself – not even for a moment. Perhaps, this is the most attractive trait of Imre Drégely’s creative personality.

His image, Lightning, exemplifies this self-ironical attitude. With one movement – that is, shining his flash on a corkscrew willow branch – he conjures lightning into the sky, while simultaneously creating an alienating effect by also including the hand holding the branch in the picture. Another composition, Man, illustrates the same approach: Drégely, first, flashes the figure advancing from next to the tripod-mounted camera (a little underexposed in order to create a slightly faded effect); then, with another exposure, he makes the image of the industrial building stretching out in the background. As a result, he creates images that do not exist in reality, but rather those that emerge purely from his inner vision. And with a grin he, again, alienates the viewer from the picture: the man has sunglasses on, which does not correspond to an evening in Budapest…at least not in this location.

The question of time

In discussions of photography, philosophers and theorists often conceive of the medium as the art of “capturing the moment,” emphasizing its “ability” to document and freeze a particular point in time. However, the only thing that is true about such theorizations is that the photograph (as opposed to film and video) is a still. In taking so-called “momentary” snapshots, fractions of time between 1/30 and 1/10,000 of a second pass—fractions that are in fact very short amounts of time, but time nonetheless.

In the early days of photography, exposure lasted hours (Niépce’s heliograph took about 8 hours); then, it became minutes (Talbotype, Daguerreotype); and with the spread of the wet collodion process, artists needed 5-90 seconds. Yet, these images also created the impression that they were “snap” shots—they exist, and we can look at them for as long as we like. This is the essence of photography, not how long the shot lasted.

© Imre Drégely, Carousel (1989)

As is evident is his work, Imre Drégely creatively addresses the question of time in the still image. He does so by using longer than usual exposures, which – like multiple exposure shots – exist not in reality but only in his inner vision. Such is the shot of the spinning, illuminated merry-go-round from 1990 that, due to the exposure lasting seconds, left an impression on the negative as if it were the “snapshot” of a UFO. Since 1996, Drégely has made a whole series using this technique. Every year on August 20th, he photographs the firework display put on in celebration of the Hungarian national holiday. In this there is nothing special. Yet, his photographs capture every firework set off in one frame—that is, the whole half-hour display is depicted in one frame. He does it by putting a 6 x 7 cm piece of unexposed photographic paper in a camera on a stand at a pre-selected location. When the spectacle begins, he opens the camera’s shutter and at the end he closes it.

Imre Drégely’s images, as all photos, are based absolutely on “reality”, but he presents us with sights that do not exist in this form. He creates a virtual world using analogue techniques.

The question of space

We know that there is no time without space, at least not in our reality. Consequently, Drégely extends his epistemological research to incorporate space as well as time. He evokes virtual spaces in the plane of the print—spaces that are actually nonexistent. This is evident in his picture collages, in which he pieces together a single image out of several independent images. This type of work emphasizes the contradiction between how the human eye works and the fixed “view” of the lens. It is not only reality that we view with a wandering eye, but images as well.

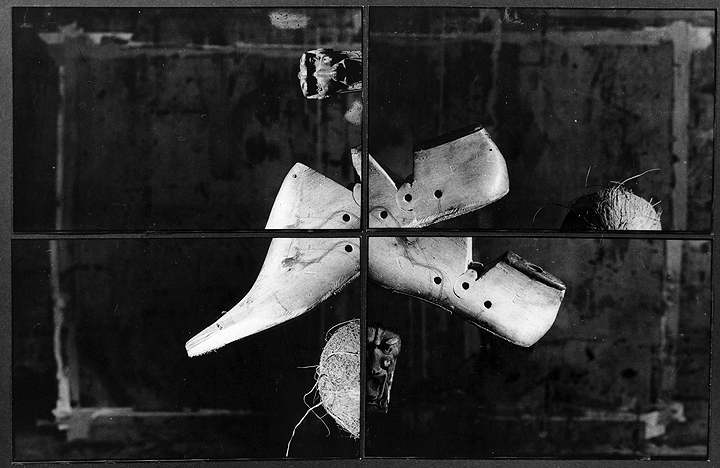

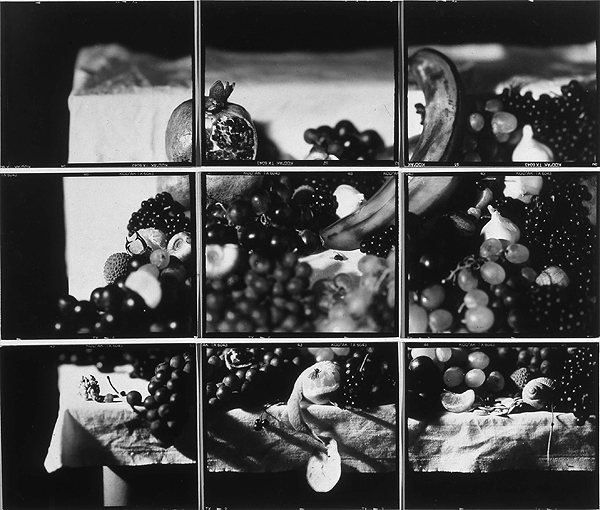

The most straightforward example is when an image comprises details of the same object from different viewpoints, thus depicting the whole model from various angles. Despite seeing the whole image, we nevertheless feel something is not quite right. Although the partial images adapt well to each other, the different viewpoints (which are also different time planes!) in no way fully harmonize. Prints of this type include: Still Life I–IV (1993), where a shoe tree is the model; or its pair Derby Patent (1996), the model for which was a classier shoe tree that can be adjusted for different sizes; then, there is Still Life I–IX (1994), which is made up of images of fruit.

© Imre Drégely: Still Life I–IV (1993)

© Imre Drégely: Still life with a fly (1994)

However, a more complex version of this type of collage image is when the details of a picture consist of substitute images. For example, Nude (1996), in which the woman’s hair is a bush, her thigh is a man’s (hairy) elbow, and her feet are replaced by shoetrees. Although here and there she is constructed by parts of her own body, Drégely gives these “real” components a twist. For instance, a part of her shoulder substitutes for her back. Thus, from a distance, it appears to be a slightly strange nude, while close up it becomes an absurd, nonsensical image.

Nothing is what it seems.

Everything is what it seems.

These two statements are paradoxically both true in Imre Drégely’s analogue, virtual world.

Fortune’s darling

The first of Drégely’s collages, the Zodiac series (1992), were completed for his college thesis. In this series, he put together five constellations, each from sixteen frames. As a result, the parts blended into each other perfectly. But if you look at them more closely there are little things that become noticeable: Aries has a fish tail, Leo has leopard paws, etc. Interestingly enough, these images seem the most mature among this type of collage from Drégely’s larger body of work, yet they were the earliest. If I am right, the “clumsiness” of his later works, the grating compilation of the details, must be intentional.

The Dice Poker series (1999-2000) also testifies to this, which at the same time serves to explain the whole concept: these images are compiled by chance made to work according to plan. The visual products, whose main lines are thought out in advance but which are nevertheless compiled by chance, may surprise the artist (and the viewer) with unexpected gifts. For example, in one image the frame puzzle results in the familiar form of Lake Balaton—a consequence that, I believe, even Drégely himself did not count on while he was shooting the various parts of the image. This is poker not just with dice, but with frames.

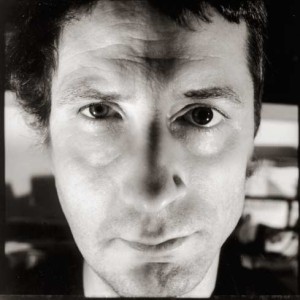

This paradoxical “planned accident” also drives the Joint Works (1997) series Drégely made with Péter Bányay (1960–2003) in which the two photographers share each frame. One of them covers half the lens, takes a shot and marks two or three lines on the focusing screen where the other half of the picture has to fit in. Next day, the camera is passed over to the other, who looks for some subject to complete the unknown half of the picture. As a result, wonderfully surreal montages are created, of which the “self-portrait” of the two photographers deserves special mention: a nonexistent, yet real being is born from the half-faces.

The question of Colours

© Imre Drégely – Péter Bányay Four-four (1997)

Obviously, it is not by chance that Imre Drégely highlights in his still lifes motifs referring to mannerist, baroque and modern predecessors: the perceived world and “reality”, the compatibility of different perspectives, illusory worlds, the genre of vanitas, the unpredictability of luck have all occupied artists (and interpreters of images) since the Renaissance.

Such a direct reference to art history – perhaps too direct – is exemplified by the Notre Dame series (1990). Inspiration for the series came from the Monet paintings Drégely saw in Paris for the first time while hitchhiking as a student. There is not much point in discussing the special colour effects of the Polaroid technology, and later the Polaroid transfer, he enthusiastically started using then, as I cannot illustrate my point without the original pictures. Nevertheless, allow me one paragraph.

Even the most perfect colour material only reproduces real colours referentially. Within this Polaroid is even worse: sometimes strikingly strident and sometimes enervatedly faint. Why, then, is it that Drégely turned to this technique? I imagine for the very same reason why he also breaks the space, the perspective, stops the flow of time, enlarges his pictures to half-sharp through double exposure (one sharp, one unsharp, as in Coat (1999)), and photographs shade instead of light and brightness. He searches for images that convey his own inner feelings instead of the external world.

This refined inner world is not just conveyed through his visions: his prints serve this purpose through their entire physical reality, their being artwork, objets d’art in the literal French meaning. The medium of photography is not merely the seen and captured image, but the print.

Besides the colours, part of the Polaroid transfer, the Polaroid dye transferred onto a sheet of paper, is the surface of the transfer paper, the impression and facture of its fibres. Likewise, a part of the fireworks images is the veining and fine fibre shadows of the exposed paper negative; the shrill harshness of the giant size belongs to his still lifes; the whispering intimacy of the miniature image belongs to his transfers.

And this is completely lost in the world of digital technology, homogenizing, and dematerializing everything. For this reason computer graphics are something fundamentally different from the photograph. Not better or worse. Simply different.

Drégely is fully aware of this: he has used traditional photography from the start as if working with Photoshop. Except, he wants to create photographic works of art, prints. But then he is a photographer and not a graphic designer taking a trip to the field of photography. And if he’s got any brains at all, he will not stray from his path, as the future of photography lies in the traditional, chemical and manual making of prints.

(Originally was published in Hungarian in Beszélő, December 2002. Translated by Christopher Claris.)

Top of Page

Return to VJIC Table of Content | Return to Thread Table of Content

- To see Imre Drégely’s photographs, visit www.fotografus.hu. ↩