Return to Theme Table of Content / Return to Issue Table of Content

This is the 4th essay in the threaded theme “On Photography” by Sándor Szilágyi.

Gábor Kerekes does an extraordinary thing with photography. He does not tell stories or

cite dramatic events, nor does he document his own emotions and moods – he philosophizes. He makes ontological and epistemological investigations; he probes the bounds of human cognition. Through photography, he seeks our place in the universe. He researches characteristics of the human sensory organs, particularly those that help us find our bearings: the eye, the ear, and the brain. But, above all, he explores the relationships between science and art.

In one sense, it is as if he merely tried to recreate the cohesion of olden times – a unity that in the 19th century, regrettably, disintegrated in both the artistic and scientific communities. Science fell apart into increasingly specialised fields and at the same time became ever more dehumanised. Art, likewise, became emptier and more self-centred as it lost contact with other forms of understanding the world – that is, from the experiences of everyday life and the sciences.

From an artistic perspective, Kerekes expresses the rediscovery – also acknowledged by an increasing number of scientists – that intuition and reason belong together after all. And he, simultaneously, explores the ever-puzzling question: can the world be known? What can the arts, in this case photography, contribute to what we know about the world and humankind?

Role-play

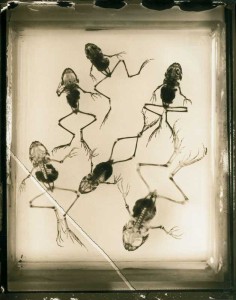

This may seem like a trivial approach but it is not self-evident, as Kerekes does not fulfil our expectations of how a photographer should act. Rather, his approach more closely resembles that of a 19th-century naturalist who happened to take photographs in the course of his research. That is to say, he uses the photograph like a scientist uses experimental equipment. An obvious indication of this is his penchant for photographing old paraphernalia such as test tubes, a lightning conductor, a dynamo, assorted measuring instruments and the like. Furthermore, he readily chooses the objectified results of the sciences (human and animal anatomical specimens, and fine examples of insect and mineral collections) as his subjects.

But we should all be aware that this is simply play no matter how seriously its maker takes it, or how successfully he has managed to construct a coherent, independent visual world through this role-play. We should not be deceived by the subject matter of his photographs. Kerekes clearly deals with photography and not science.

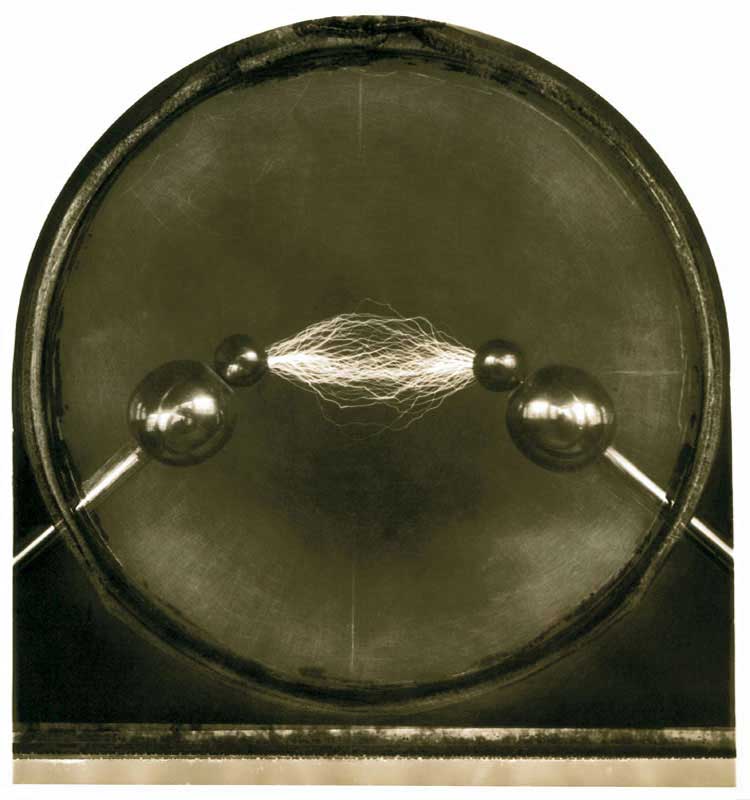

This immediately becomes evident upon closer inspection of his pictures, many of which are in fact a result of his sleight of hand. What, at first glance, appears to be a planet bearing the scars of cosmic impacts is, in reality, a ball-shaped lightning conductor; the sunrise shot of a planet in space is of a tennis ball taken within the walls of a studio; the small planet surrounded by stars is a Starking apple, and so on.

The illusion is perfect, and these are not mere comparisons. Kerekes is not saying that a lightning conductor is like a planet, and that a rubber ball or apple shot with the right lighting are like celestial bodies. Through the means of photography he creates these heavenly spheres. He imbues everyday objects with cosmic significance. This is not natural history, but the purest photography, indeed photomagic.

The rediscovery of photography

Kerekes goes back to the 19th century not just in his subject matter, but also in the appearance and processing techniques of his pictures. In and of itself this is nothing special. Around the world – and here in Hungary, too – many people use the so-called historical, alternative, manual photographic techniques. Yet, Kerekes goes radically further than this: the whole point of his role-play is that he did not stop at the pictorialist aesthetic that almost automatically follows from the use of manual techniques. At the same time, he was not swept away by shockingly upsetting taboos, nor has he been carried away by the intoxication of the digital manipulation of pictures. With his particular archaizing of his prints, he has created for himself a very modern photographic language.

His images of antiquated effect not only evoke the 19th century, but also the first half-century of the history of photography – an age characterized by the naïve and functional use of the photograph prior to pictorialism – when photography was a novel discovery itself. He reminds us not only that it was used for geographical and scientific discoveries, as Kerekes indicates with his chosen subject matter, but also that photographers of that time had to discover the medium itself, its possibilities and limitations, and frequently even its fundamental techniques. No doubt, this is a kind of gesture of respect to our forefathers and foremothers – but it goes deeper than that.

For one thing, together with the maker of these images we can relive all the charm of the first, hesitant steps of the birth of photography. It is not by chance that, despite his perfectionism, Kerekes almost provocatively accepts the flaws of photography – the blistering of hand-coated emulsion, the broken glass of the specimen of frogs’ skeletons, a storage label spoiling a museum lithograph, the crookedness of the edges of the picture, and the streaking of astronomical images. These “imperfections” of his flawlessly executed photographs perfectly correspond to the form and content, the model, and what you see in Kerekes’s photographs. Their role is to remind us of the fallibility of the world, of the medium of photography, of the artists creating it, and of the viewer taking in the sight. Leaving in the flaws, for Kerekes, is about visual philosophy and not pure aestheticizing.

The future of photography

Besides this, the radical step back in time has another consequence in terms of the philosophy of art. Kerekes deliberately pushes aside the lot: today’s, yesterday’s, and the day before yesterday’s art photography. He deliberately goes further back, precisely because he is seeking an idiom that he knows will be valid tomorrow and the day after tomorrow. That is why he does not stop at the pictorialist aesthetic although this once produced excellent results with manual techniques, which he, too, has used. However, Kerekes does not wish to indulge in nostalgia. As we have seen, for him the role of the naturalist is not immersion in the past, but rather an intellectual link to the most modern scientific endeavours. This is how the role-play, the subject matter arising from it, the chosen techniques, and the artistic self-reflection blend into a perfect whole within Kerekes’s work.

At the same time, this creative gesture returning to the pre-artistic era of photography speaks of no less than the future of the medium. This is most simply expressed by a paradox: it is digital imagemaking that will truly turn traditional photography into art. And why? Because it will free it from a number of tasks foreign to art. Applied photography (the scientific, advertising, and press photograph) will sooner or later go over to digital techniques; digitization is also the future for snapshots, and the new techniques’ independent artistic use is also developing – in multimedia and computer graphics.

Thus, the traditional, chemical-based, manual photographic techniques (including the nowadays already and still most accepted silver gelatin process) will become more valuable primarily because they can only produce a photograph as a work of art. And obviously, it is also because there will be fewer and fewer people who know how to produce it, and thus the photograph will acquire rarity value.

Alt-chemistry

The proper form of appearance of multimedia and computer graphics is not the photograph as an object, the print, but a virtual picture displayed on a screen.

Kerekes knows this very well, but he didn’t calculatingly set out to learn the old techniques from books at the price of many hundreds of hours of hard graft and experimentation. Most importantly, his already mentioned perfectionism and the aesthetic considerations closely connected with it led him to such obscure processes as salted paper, albumen, printing-out paper and alike.

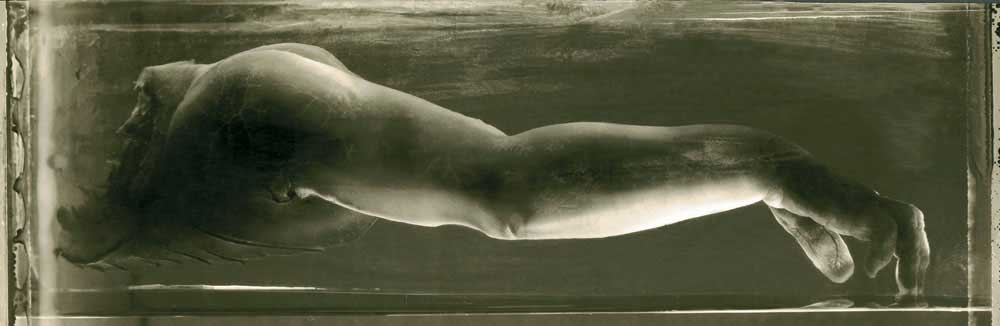

This perfectionism consists of the fact that these old techniques are in numerous respects more nearly perfect than their more modern descendants in use today. Their resolution is higher, they render tones more subtly, and as they are contact rather than enlarging processes, that is the negative is as large as the finished photograph, they are sharper and somehow “more real” than the raw materials of today.

This in itself already has aesthetic consequences. In addition to this, salted paper – with only slight exaggeration – is like a living creature. As there is no binder, the picture develops on the paper’s diaphanous matt surface, and under it every fibre of the paper almost palpitates, Or if we look more closely at albumen, it is subtle in a different way: it has a lustrous, shiny surface. Silver chloride printing-out paper also surpasses the capabilities of silver bromide enlarging papers in many respects. Moreover, we should remember the wonderfully deep, brownish black tones of all three photographic papers. This phenomenon is produced by immersing the photograph in a bath of gold chloride, as Kerekes the Grand Master is apt to do with them.

Universe

So Kerekes does something exceptional: he philosophizes with pictures. He does not use them to illustrate complete tenets of philosophy or religious philosophy, such as those of Zen, but through them evolves a personal visual philosophy. He examines the universe. He tries to make it talk. He looks at the world around him as if from above, but not as if he imagined himself as God. He wishes to separate the significant from the insignificant to create timeless works. This is why he does not photograph people—subjects that would only disturb the clarity of his vision with each person too incidental, minute, fallible. Like this, the world is cosmically desolate. In this way, his work reminds me of the poetry of János Pilinszky and the music of Laurie Anderson.

Will Kerekes ever reach the point where he communicates with the world, and about the world, through the human face, through portraits? I for one would be delighted if he did, as I would interpret this as the world at long last being ripe for Gábor Kerekes to forgive it. And who would not want to live in a world like that?

Translated by Christopher Claris.

[A version of this text was originally delivered at the exhibition opening for the Nyitott Műhely (Open Workshop) Gallery on 4 March 2002. It was first published in Hungarian in Beszélő, April 2002. Gábor Kerekes (1945–2014) is considered by many – including the writer of these sentences – as being one of the most important photo-artists of post-WWII Hungarian Art Photography. The illustrations are from the section “YEARS – 80′- 2K” of his website, http://w3.enternet.hu/kgj/images.html.]