Sándor Szilágyi, PhD, is a Hungarian media theorist, writer on photography, living in Budapest, Hungary. His interest range from Hungarian art photography, documentarist photography, and the theoretical questions of photography.

This is the third of ten essays on photography by Sándor Szilágyi.

VASA thanks the Hungarian Museum of Photography for permission to reference and link to

the images in this essay.

The Hungarian Paradox

Hungary is a small country, but a great power in terms of photographers: the names of Kertész, Brassaï, Moholy-Nagy, György Kepes, Robert Capa, Stefan Lorant, Martin Munkacsi, Lucien Hervé and a good few other Hungarians could not be omitted from a history of photography. This is ample reason for national pride – although it would be more correct to talk about artists of Hungarian origin, as they did not produce their oeuvres in Hungary. And, to be even more precise, they were mainly Hungarian Jews who fled the country between the two World Wars not simply because of the intellectual milieu stifling their talent but also because of the specter of racial or political persecution. This does not detract from justified national pride: I mention it merely to give a fuller picture.

At the same time – and this is the Hungarian paradox – the world does not really value the photographers who worked in Hungary at that time. Rudolf Balogh, József Pécsi, Károly Escher, Olga Máté, Nándor Bárány and other prominent figures from Hungarian photography are usually passed over in histories and encyclopaedias, although many profess they are significant artists whom the world ought to take note of.

I do not share this view and will tell you why.

Amateur late pictorialism

In the early, heroic age of photography everything was just fine: Hungarian photography was up to date. A couple of weeks after the report of Daguerre’s invention the Hungarian public knew about it and a year later a manual in Hungarian – although published in Vienna – spread the knowledge of the invention. Shortly afterwards Daguerreotypists started working in Hungary. Later, Hungarian traveller/explorer photographers (Pál Rosti, Balázs Orbán), natural science photographers (Loránd Eötvös, Jenő Gothard, Miklós Konkoly-Thege) and professional photographers (György Klösz, the Divalds, Mór Erdélyi, Manó Mai) were no worse – alas no better either – than their contemporaries likewise busying themselves in other parts of the world. The Hungarian inventors József Petzval and Ferenc Veress even pop up in the international vanguard.

So for the first sixty years everything was just fine – only from the aspect of the theme we are concerned with, the history of photography as art, this is of no significance, as this was before photography as art existed at all.

Photography as art creating lasting values was born with pictorialism precisely as a counter to the amateur dilettantism of club photography. In England the decisive step was the establishment of the Linked Ring Brotherhood in 1892, while in America in 1896 Alfred Stieglitz came to the helm of the New York Camera Club, then a couple of years later, in 1902, announced the Photo-Secession.

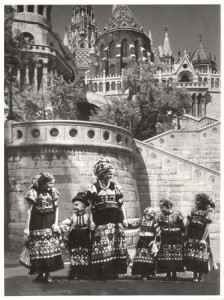

Rudolf Balogh: Matyó mother with five kids in front of the Fishermen’s Bastion, 1935. Permission: Hungarian Museum of Photography

In Hungary, however, something entirely different happened. The Hungarian amateur movement began a good decade later than in other European countries. It only started to take shape in 1904, which in itself is no real problem. What is, however, is that as a result of the delay it set out in the spirit of readily adopted pictorialism! To put it the other way round, as this is really the point: Hungarian pictorialism was amateur beyond help, third rate and imitative. I think it does matter whether a Stieglitz, Käsebier or Steichen sensitised their paper by hand or dilettanti like Zoltán Kiss, Géza Szakál or Dr Győző Kemény did so.

And what is even worse is that our truly talented photographers such as István Kerny, Iván Vydarény, Angelo (Pál Funk), József Pécsi, and Rudolf Balogh were still working in the pictorialist spirit when the rest of the world had long ago moved on. Just look at the catalogue of the 2nd International Art Photograph Exhibition in Budapest − from 1927!

The “Hungarianisch” style

And that’s not all! In Hungary it was not just that pictorialism was intertwined with the amateur movement, and or even that it had outlived itself. In Hungary the rejection of pictorialism was likewise ambiguous, dilettante.

In America at the turn of 1916-17 Paul Strand and in his wake Edward Weston, Margaret Bourke-White, Ansel Adams and others created the modern, Straight Photography by breaking with the pictorialist approach lock, stock and barrel. But one element – the most important one – they took with them: the requirement that a photographic work of art, a print, be a manual creation of exceptional standard.

In Hungary between the wars, the representatives of the emergent Hungarian style demanding modern (or rather semi-modern) photography did exactly the opposite. Although they radically changed the printing syntax of photography, the external appearance of the print, in that the gloss print – what’s more a print “glazed” with the aid of a heated chrome sheet – was favoured,1 they retained the most important component of pictorialism’s camera syntax: the cult of the soft-focus lens, emphasising the highlights in part by a supplementary softening lens, in part by shooting “backlight” opposite a source of light. These are only the external signs, the signs of form, but they already betray a crude dislocation of taste, the ambiguous “progress” of photography imitating painting.

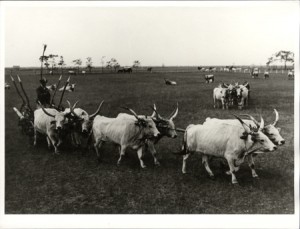

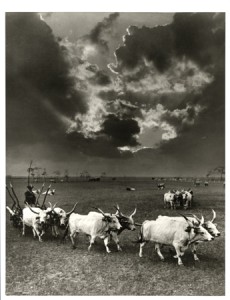

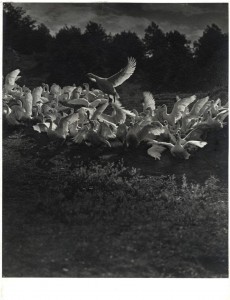

More importantly than this, however, the Hungarian style not merely “modernised” the softening aestheticism of pictorialism, but also – and clearly not divorced from this – preserved for posterity its idealizing pictures of people and nature. I know of no one who has actually noticed the curious parallel2 that Edward S. Curtis, who started as a pictorialist, and got stuck in it, photographed the North American Indians in the same lying and idealizing manner as the photographers of the Hungarian style – Rudolf Balogh, Ernő Vadas, Kálmán Szöllősy, Tibor Csörgeő and others – did the villages around Budapest. (NB villages of the assimilated Swabian or Slavic minorities in Hungary.) Curtis made his subjects put on ceremonial dress, on top of which he even stuck “Indian” wigs and headdresses out of the props basket on their heads, and put copper rings in their noses and ears for the sake of an aesthetic effect. But where was all this between 1907 and 1930, when the shots were taken – and which, not surprisingly, have a nineteenth-century feel? Rudolf Balogh’s romance of the plain and peasantry, the Hungarian -style’s “pearly bouquet” of rural idylls were similarly anachronistic occurrences.

To avoid any misunderstanding, the trouble with the Hungarian style was not its folk subject matter, but its untruthfulness.3 Out of this arises -like the chicken and the egg of course- its false aesthetics. This is why it couldn’t be Hungarian, only Hungarianisch, and by no means folk, merely folksy. This was the wrong answer to the contradictions of modernisation, and industrial and urban society.

Unfortunately, it wasn’t the only wrong answer. In an aesthetic sense the reverse of the Hungarian style, the committed left-wing, politically progressive, socio-photography (Kata Kálmán, Kata Sugár, Judit Kárász, Kassák’s circle) from an aesthetic viewpoint produced similarly ambiguous, idealizing results. It seems there’s no mistake about it: if we approach people with ideological presuppositions, if we only see them as representing a social category, then all we get is stereotyped answers and ideological intimations.4

Recto and verso: it is no coincidence that later Hungarian social realism during the communist era was stitched together from elements of the Hungarian folk style and socio-photography – by often the very same semi-amateur photographers, and photographing writers and pioneers of the movement who between the wars occupied themselves in one area or the other.

The Hungarian “orange”

Representatives of the belated, semi-amateur Hungarian pictorialism that outlived itself and of the pure-bred amateur Hungarian style that was raised to a quasi official status have no place in the universal history of photography. And socio-photography that appeared in opposition did not enrich the photographic way of seeing in any way. The world has not lost a thing by not knowing about them. That’s the sad truth of the matter.

There were, however, figures in Hungarian photography between the two world wars who, if not in the international vanguard, were in the second or third rank, albeit if in the applied genres of photography.

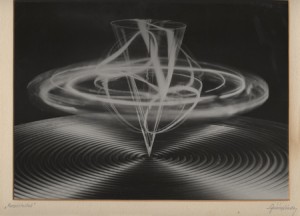

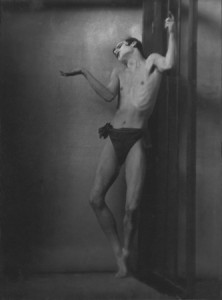

Above all, the work of the advertising photographer (and writer on photography) József Pécsi deserves mention. In these areas he was a true pioneer in many respects. His artistically motivated images, however, are almost as if Drtikol had made them – only Pécsi was somehow less bold than the experimenter from Prague.

Rudolf Balogh’s Hungarian style and country propagandist idealism have already been mentioned, but his earlier “realist” work from the First World War is by no means without interest. It’s a shame that he didn’t go further in this direction. Károly Escher was also good in an applied category: in his photoreports he applied a Moholy-Nagy-/Rodchenko-like overhead view with a remarkable aesthetic sense (Ernő Vadas produced more modest results in the same way), although Escher, too, is only in the second rank of the Constructivist-Bauhaus style.

I believe more attention should be given to Olga Máté, who used the abstract, geometrical approach of Straight Photography, and did so very finely. Her career has many parallels with Margaret Bourke-White. Nándor Bárány’s photographic nonsenses, his grotesque and almost bizarre way of seeing were an entirely special phenomenon; the only comparison that comes to my mind is (the slightly commercial) William Mortensen.

Of course, no harm will come of it if the wider world gets to know the life’s work (or the best of it) of the above mentioned. But let’s not kid ourselves: even for their sake, there’s no need to rewrite the history of photography. Not one of them is of comparable stature to Sudek, Kertész, Cartier-Bresson or Brassaï.

It would be good to finally lay the ghost of the double standard of national inferiority. We need to learn what is the lasting achievement of original talent and what is the fleeting imitation of fashion – not only in the past, but in the present, too.

We should call a lemon a lemon, if it’s small, yellow and tart, rather than lie that it’s a Hungarian “orange”.

(First published in Beszélő, November 2002. Translated by Christopher Claris.)

- Followers of Straight Photography either used platinum-palladium from the start, that is matt photographic papers, or gelatin silver papers dried semi-matt. ↩

- Not even Károly Kincses, in the time writing this essay the director of Hungarian Museum of Photography, in his otherwise excellent review Mítosz vagy siker? A magyaros stílus Myth or success? The Hungarian style. Hungarian Museum of Photography, Kecskemét, 2001. ↩

- Counter examples are Béla Bartók’s music, and the folk roots of the poetry of Attila József or the sociology of Ferenc Erdei. ↩

- Nowadays the basis of ideologically motivated photography is not any more social class but race and gender and its theme is not work and struggle but entertainment and sex. However, clichés remain naturally clichés. ↩