This is the second of ten essays on photography by Sándor Szilágyi.

The American modernism

Straight Photography

The manual technique of pictorialism was too demanding, involving too much work and money, and for this reason it could not continue for long. Furthermore, the ever-expanding choice of materials—i.e. newly available (and cheap), attractive photographic papers that could be bought over the counter and were easy to handle—improved the photographic results and process.

Around the time of the First World War, the Photo-Secession with its principles of beauty and idealized aestheticism no longer fit the spirit of the time. Instead, Modernist efforts introduced new ways of seeing into the fine arts (fauvism, cubism, expressionism, etc.), which “art photography” with its newborn consciousness wanted to contribute to; this led to a significant shift in the photographic era.

The first major movement1 of photographic modernism emerged in America in 1916 with the appearance of Paul Strand and the announcement of “Straight ,” or “Pure Photography.”

In addition to Strand, the most prominent figures in the twenties and thirties were Edward Weston, Ansel Adams, Charles Sheeler, and Imogen Cunningham; but the new approach later spread to such individuals and genres as the photoessays of Margaret Bourke-White and W. Eugene Smith, or later, the abstract images of Minor White, Aaron Siskind, and Paul Caponigro.

Straight Photography was a direct denial of pictorialism. According to the new canon a print should be a print, not a painting or charcoal drawing; photography, its own medium, does not need to mimic these. The followers of the new school, who had all begun as pictorialists, now rejected manipulative photographic printing techniques, while at the same time—and this is very important—took the maximalist, quasi-manual requirement of creating photographic artworks further.2

Literature on the history of photography deals with this issue one-sidedly, only mentioning the break with the pictorialists’ manual processes. However, as a result, the element of continuity is completely lost. Yet if the medium of art photography is seriously considered as not simply the seen and captured picture—the image—but a print made with artistic standards, the perfectionism Straight Photography takes further in its printing syntax3 is of extraordinary significance. This is important in itself, as remarkably beautiful artworks were created in this spirit; but, more than that, it is fundamentally significant. As it will be shown, this is a decisive argument for why the use of, and experiments with, photography by avant-garde artists should not be regarded as a renewal of art photography.

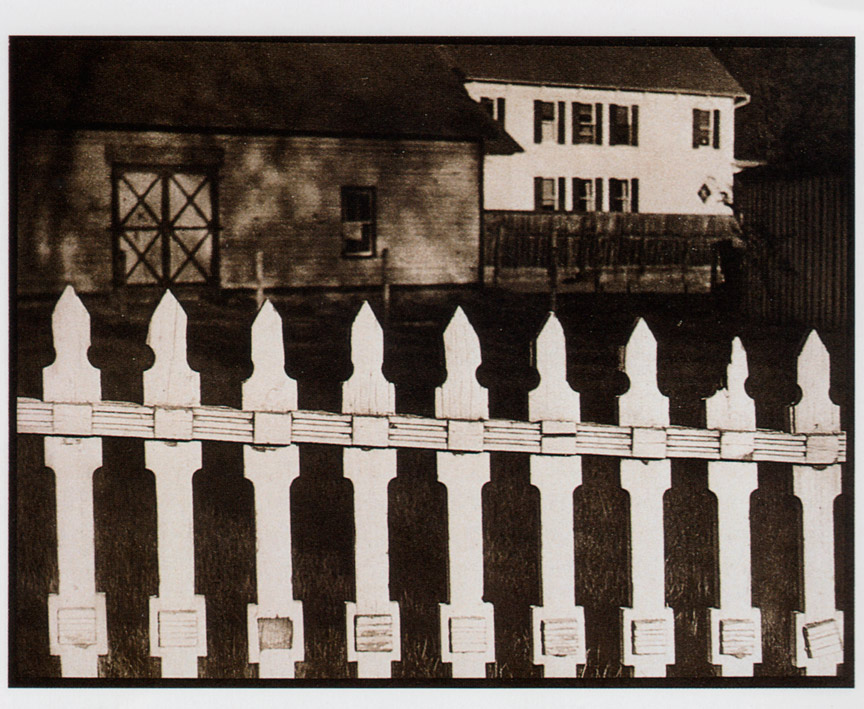

Perfectionism characterised the camera syntax and shooting technique of Straight Photography. In America, large format, the camera on a stand, and correction of perspective—all that was the everyday language of nineteenth-century photography, and what this movement “merely” took as artistic perfection—were basic requirements, not only in artistic photography but also in applied photography—i.e. press, fashion, and architectural photos—and, even, documentarianism.

However, it was not only in its use of tools—and thus, style—that Straight Photography was modern but rather, in its entire approach. Its representatives turned to given (and not arranged) images, the visual abstraction (and not aura) of industrial and natural landscapes, the human body, and face. Abstractions were extracted from their realistic bases, divorced from their true environment and offset against each other. Weston’s photographs best illustrate this: he saw and showed landscape as a human body and the human body as a detail of landscape or part of a plant; for instance, a pepper as a human back and an artichoke cut in two to resemble that particular lusted after part of the female anatomy. It is not hard to recognise the renewal of the Secession’s organic abstraction and pan-eroticism.

It was also part of the modernist, abstract way of seeing evident in Straight Photography that its practitioners discovered the functionalist aesthetics of engineering works—i.e. the rational order and beauty of regular geometrical figures and straight lines, in addition to organic and irregular forms.4 Along with this geometrical, abstract way of seeing, the principle of pars pro toto was applied more and more boldly and not only in landscapes and shots of buildings, but in the instances of human representation, as well (which until then had been taboo in photography).

Against the mainstream

It is of particular interest that practitioners of Straight Photography, quite consciously, professed the possibilities of the new artistic medium in their writings. However, there is no trace of this in the summaries of art history, although they would have fit in perfectly with contemporary theories of art such as Werner Hofmann’s, The Foundations of Modern Art. This prompts the question: was their language too specialized, or technical? Perhaps. But it is probably more than that, as the history of art (at least in Europe, and especially in Hungary) has, until the present-day, failed to acknowledge that with pictorialism—and its modernist sequel—a new autonomous branch of the arts was born: art photography.

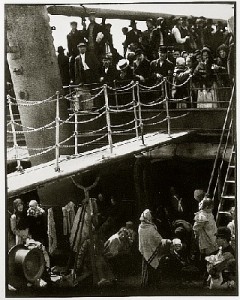

Alfred Stieglitz, Steerage 1907

w/permission: George Eastman House, International Museum of Photography and Film

But why are we still striving to prove this today? Undoubtedly this is because the main ambition of art photography was to create, and then perfect, the panel picture by photographic means, while the main problem of modernist artistic movements was discerning what to do with the traditional perspective of painting inherited from the Renaissance and the role of artistic individuality. Furthermore, as art photography is a technical creation of an image, this also posed the question of how individual taste and artistic style is created through mechanical, optical, and chemical processes. Thus, in the fundamental issues—i.e. the perspectival, panel picture and the individuality of the artist—the autonomous efforts and thoughts of art photography posed a challenge to the mainstream discourses of modern art.

Additionally, these works and perspectives developed in America, while modern art and its theories came from Europe. It is no coincidence that photography as a new branch of art first took root and was allowed into the exclusive world of high art in America. Pictorialism’s most important representatives worked or appeared there, and “Straight Photography” was in fact an American school. As Paul Strand himself said with no little self-confidence, “America has really been expressed in terms of America, without the outside influence of Paris art schools, or their diluted offspring here.”

From Europe there is really only one representative of “Straight Photography”—Albert Renger-Patzsch.5 Large-format, slightly rigid painting-like abstraction radiating eternity was a rare phenomenon in Europe. Instead, in Europe, modern photography as art sought different ways to express itself.

The European ways of modernism

Anti-photography: the graphic use of the photo

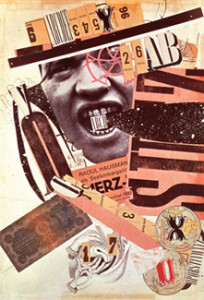

The approach associated with artists like Man Ray, Moholy-Nagy, Rodchenko, El Lissitzky, John Heartfield, György Kepes, and other avant-garde artists is particularly well-known. Indeed, too well known, considering their work ultimately renewed the form of expression in the fine arts, rather than in photography. The real essence of their endeavours can best be described as the applied graphic use of the photo.

Artists in the spirit of Dada, Futurism, Constructivism, and the Bauhaus discovered photography as a technical tool for themselves and used it without constraint in their work, as if they were using a pencil, pen, or brush. These artists were more interested in drawing with light (excuse the play on words) than photography.

What they produced were not real photographic prints, either. On the one hand, they created applied graphic works (advertisements, posters, book covers, cover pages and illustrations for periodicals) made by graphically reworking found photos (objets trouvé)

and newspaper cuttings (montage, collage, over drawing, phototypography). On the other hand, through optical and chemical experiments, they created images and prints that exploited and exaggerated photographic faults (Sabattier-effect, tilted horizons, steep perspectives, reflections, kinetic plays of light, negative or heat-treated images on paper, etc.),6 or those images requiring minimal use of photographic tools like the photogram. Of these, only the tilted horizon and steep-perspective proved to be lasting innovations for photography; the rest remained what they were: experiments in the fine arts.

This could be called anti-photography as these artists rejected or ignored all that photography ever could do or could have done.7 They did not even set out on the route on which the photographers of Straight Photography tried to renew and perfect the language of photography. I repeat, their tools were the extreme exaggeration of photographic errors, “photographing” without a camera, the graphic reworking of photographs and the like. They produced very exciting, new and effective images – but they had almost nothing to do with photography.

Of course, they were well aware of this, too. Their writings do not reflect a consideration of photography as an individual branch of art.8 It is worth repeating that this is not what interested them, and it should also be added that none of them considered themselves photographers. Even Rodchenko, who perhaps had the best grounds for self-identifying as a photographer, did not do so; and it is no coincidence that he returned to painting at the end of his career.

Curiously enough, the artists who looked down on photography were the ones who succeeded in drawing this new medium to the attention of art historian, heads of museums and galleries, and art collectors in Europe (as opposed to America), not the true photographers.

Personal-lyrical photography

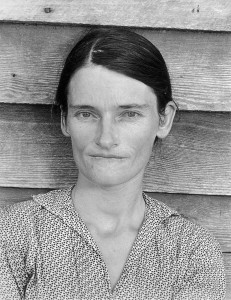

In Europe, at the same time, there was renewed interest in classical photography on par with the development of Straight Photography. This was a kind of personal, lyrical, and sometimes philosophical photography practiced by such lonely giants of photography as the child prodigy Lartigue, Atget from the 19th century, Sudek, the “goldsmith” from Prague (I mean whatever he touched turned into gold), the lyrical Kertész, the bohemian Brassaï who started in his wake, the elegant Cartier-Bresson, and then Koudelka who sang of the suffering of being an exile, among others.

It is clearly impossible to list them under the same stylistic movement. So what then do they have in common? Perhaps, just that they attempted to continue the concept of the “artist” that the Renaissance bequeathed us. This gives their photos a trace of fresh charm, especially compared to the above-mentioned, painfully thought out avant-garde experiments.

While, in America, it was Straight Photography’s rigid eternity that became the trend, in Europe this lyrical, sometimes meditative or dramatic way of seeing, capturing the magic of the moment—the unexceptional conjunction of things—came to dominate not only in art photography but also in applied photography. This was especially the case with press photography, but also (a little more harshly) in fashion and advertising photography, and even in documentary genres. This was complemented by all that proved to be lasting from graphic photography and what was taken by both from avant-garde film—that is, the distortions of perspective in the tilted horizon, steep-angle, and the wide-angle lens.

Naturally, the speed of the small Leica format cameras (which could be held by hand) also made a difference. It is no coincidence that Cartier-Bresson saw the essence of photography in the “decisive moment.” Somehow in Europe the belief persisted that things do not only have a visual appearance, but also an aura—a hidden essence—which only shows itself in exceptional moments to exceptional people who recognize this moment.

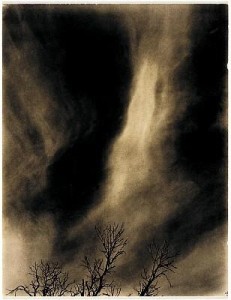

Alfred Stieglitz, Equivalent 1930

w/permission: George Eastman House, International Museum of Photography and Film

Since the 1930s, with the exception of the occasional resurrections of pictorialism and the graphic use of the photograph, nothing aside from the blending of American abstraction and European subjectivism has happened in art photography. A great number of individual accents, styles, astonishing choices of subject, and shockingly interesting concepts have been born, but a new photographic way of seeing has not been born since then. And, given its nature, none can.

(This essay was originally published in Hungarin in Beszélő, July/August 2002. Translated by Christopher Claris.)

Notes:

- After some precursors: see some of the works of Frederick H. Evans, Alvin Langdon Coburn, and Alfred Stieglitz from the turn of the century. ↩

- Strand, Weston, and Bourke-White, until it finally disappeared from the market in 1937, insisted on the platinotype as the proper medium for artistic photography, and others (besides working with platinum and palladium) were, by this time, achieving unimaginable beauty with gelatin silver bromide papers. ↩

- The camera and printing syntax category pair was introduced by William Crawford in his book, The Keepers of Light – A History & Working Guide to Early Photographic Processes, Morgan & Morgan, 1979. According to this, the syntax of the print as a visual statement is determined by what and how it is recorded in the negative, that is the angle of view and resolution of the lens, the size, sensitivity, colour sensitivity of the material used for the shot, the time of the shot, the characteristics of the chosen developer, etc. (this is camera syntax and shooting technique). On the other hand it is determined by how the print is made, the copying or enlarging technique: the chosen process, the type of paper and its surface, and tone modifying (“toning”) processes used, etc. This is very well known by practising photographers but much less so by art or photography historians writing on photography, critics and theoreticians, although, as it is about the technical creation of an image and its print, it is exactly these differences that determine the stylistic features or characteristic elements of an artist or movement. ↩

- Surely we can believe her when Bourke-White remarked, “a dynamo is as beautiful as a vase.” ↩

- Under the title the New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit), which in itself is misleading and also came to cover the whole of Straight Photography in Hungarian literature on the history of photography. Nevertheless New Objectivity, the German artistic movement represented by the paintings and graphics of Otto Dix, George Grosz and Max Beckmann had nothing to do with the photos of Renger-Patzsch, not to mention Weston and alike. ↩

- See László Moholy-Nagy: photography. In id.: vision in motion. Paul Theobald Company, (Chicago), 1947, pp. 170–215. ↩

- This artistic attitude to photography was the archetype of the neo-Avant-garde artists’ using photography in the 1960s and 1970s. ↩

-

It is true that at the 1929 large-scale international exhibition Film and Photo European and Russian avant-garde artists appeared together with the representatives of the American Straight Photography. This, however, was a one-off occasion, what’s more it happened post festa, and there is no sign that at least subsequently due to the joint appearance they would have had any effect on each other. It very much seems that, apart from their left wing political commitments of the most varied motivation, they had nothing in common whatsoever. ↩