This is the first of 9 essays on photography by Sándor Szilágyi

Sándor Szilágyi (b. 1954) is a Hungarian media theorist, writer on photography, living in Budapest, Hungary. His main interest are Hungarian art photography, documentarist photography, and the theoretical questions of photography. He has autgored books, essays and articles, and gives lectures at universities and clubs, on these subjects. Sándor Szilágyi earned his PhD degree in 2013 (University of Pécs); the title of his dissertation is Anti-Photography: Photography as the Medium of Art in the optico-pedagogical system of László Moholy-Nagy. His books on photography are: Ansel Adams zónarendszere [The Zone-system of Ansel Aadams], Pelikán Kiadó, Budapest, 1995, pp. 50. Neoavantgárd tendenciák a magyar fotóművészetben,1965–1984 [Neo-avant-garde trends in Hungarian photo arts, 1965–1984], Fotókultúra – Új Mandátum, Budapest, 2007, pp. 425(http://www.tankonyvtar.hu/hu/tartalom/tamop425/0052_2A_fotoelmelet2/adatok.html). A fotográfia (?) elméletei [Photography (?) theories], Vince Kiadó, Budapest, 2014, pp. 324.

(Editor’s note: All videos are under copyright by Sándor Szilágyi and VASA)

Definitions

Let us begin at the beginning: what is photography? Not as a form of art, but photography in general. Photography could be defined as a form of human communication through which a wave motion is fixed as a still picture on a carrier (paper, glass, metal, etc.) by optical and chemical means. This wave motion is mainly light but does not exclude other forms invisible to the human eye, such as radio, heat, UV and infrared waves, as well as X-ray.

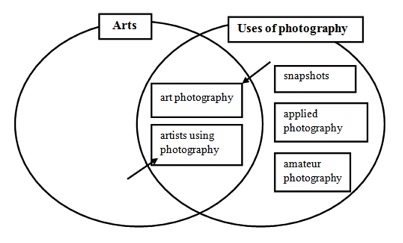

Photography for the purposes of art is clearly only a minute sliver of this—the subdivision where artistic and photographic communication intersect with each other. From the perspective of art, it is a work created by photographic means. From the perspective of photography as a whole, art photography is photography that is neither amateur, nor applied (and not a mere snapshot, either).

I believe that using this very simple dual-perspective definition not only helps us to get our bearings in today’s jungle of photographic use, but also helps us to understand the history of photography – and, above all, to see that the cultural history of photography does not coincide with autonomous art photography either in space or in time.

I believe that using this very simple dual-perspective definition not only helps us to get our bearings in today’s jungle of photographic use, but also helps us to understand the history of photography – and, above all, to see that the cultural history of photography does not coincide with autonomous art photography either in space or in time.

Regrettably, this distinction is not made even in the most distinguished overviews of the history of photography, resulting in an issue precisely because the existence and qualities of autonomous art photography are hard to perceive as they merge into the greater whole. Art photography’s loss of its most distinctive trait which sets it apart from all other photographic use—the medium of art photography is different from that of photography—is a problematic consequence of this oversight.

The medium of art photography is the print, and not – as in all other photographic use – merely the captured sight, the image.1 The Print is made for art’s sake and intended for exhibition, or sale, as art; a print is made, or at least approved, by its maker.

With this in mind, it can now be understood that in the first half century of the history of photography, art photography did not yet exist. It only began in the early 1890s with the birth of pictorialism, both in a sociological and aesthetic sense.

Before pictorialism photography was used in a naïve form: naturalists, travellers, explorers, archaeologists and in their wake tourists documented their special visual experiences. Besides this there was also an “applied” form: studio photography, practised mostly by painters who had trained themselves to be photographers. Practising painters also used the photograph as a technical aid, both because it was cheaper than painting from life and because it was more exact than drawing a study. But, I repeat, art photography did not exist, as within photography there was nothing to compare the pursuit of art against – and the whole of photography was obviously not art.2

The birth of art photography

Art photography is photography that is not amateur and not applied. Before pictorialism, art photography cannot be talked about, as this duo, amateur and applied photography, likewise did not exist. So, what brought them into being?

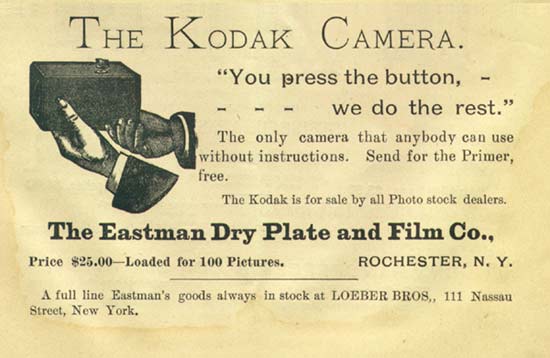

Kodak’s famous slogan from 1888 (“You press the button, we do the rest”), or rather, the institution of photo labs operating as a service divorced from the taker of the image (and also of course the mass production of raw materials and devices) revolutionized the cultural history of photography. On the one hand, the production of snapshots appeared, which virtually required no knowledge or manual skill to produce (and so it is today). On the other hand, and this is very important, as a counter effect of this, there emerged the movement of serious amateurs for those who wished to continue to process their own films and prints: photography magazines were launched, and photography clubs and salons sprouted one after another, whose walls were covered with members’ photos from floor to ceiling,3 as well.

Art photography was born as a counteraction to this amateur dilettantism. It was not by chance that it was called the Photo–Secession in America, as it tried to distance itself from the world of photography clubs.

But let us look at the other side, which the new artistic movement also disassociated itself from: how did the applied forms develop? The invention of the rotary printing machine and half-tone, autotype reproduction of photographs in the 1880s enabled photographs (or more precisely, as this is the real point, reproductions of them, broken down into a grid of tiny dots) to be printed with text, resulting in the mass use of photo reproductions by the press.

With the photo-illustrated press, again the cultural history of photography as well as the psychology of acceptance was revolutionized: this was the beginning of the process whereby people mostly encountered reproductions and not original photographs (prints)—and what is more, in an unprecedented quantity, which has been burgeoning ever since. The sum of press, periodical and album photography can be described as applied photography.4

As a counteraction to applied photography existing merely in reproduction and on the other hand dilettante amateurism alas creating original photographs, the photographic print as an artwork was born in pictorialism: the original print in terms of graphic reproduction (a limited number of copies handmade by its author) for an artistic purpose, and its execution intended for autonomous artistic exhibition and sale as a work of art. And so art photography was born.

Avant-garde pictorialism

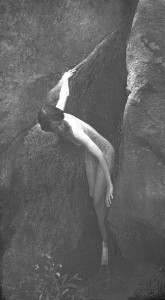

Anne Brigman the Cleft of the Rock 1912 Permission: George Eastman House, International Museum of Photography and Film.

Pictorialism, from its inception in 18925 right up until the appearance of Straight Photography in 1916–17, played a progressive role in the history of photography.6 Under its influence the institution of the exhibition of photography as art was created, where the walls were not smothered in pictures from floor to ceiling as in the amateur clubs and salons, but were arranged as we have since come to expect: beside each other, properly mounted and framed, bearing in mind even the colour of the wall, and devoting particular attention to how the photos are lit.7

However, it was not just the exhibition of photography as art that pictorialism brought forth, but the photograph as an artwork itself. Although these prints were made by awkward manual techniques which have a seemingly obscure effect today (oil and bromoil, carbon, gum print, platinotype and their like), and their aesthetic canons are also perfectly out-dated, whoever has seen original prints from the period by Edward J. Steichen, Alfred Stieglitz, Clarence H. White, Gertrude Käsebier, Frederick H. Evans, and others knows that they were lucky to see manually-prepared photographic prints of unparalleled artistry and craftsmanship.

As regards the out-dated aesthetic canons, the principles they embodied were considered revolutionary in their own time. When the pictorialists took the camera to nature, that is they did not use a painted background in a studio but nature as a backdrop for nudes and portraits, or when all-weather photography began in rain, fog and snow, and subjects such as cityscapes (ports, railway lines, silhouettes of buildings, etc.) like Japanese landscapes were placed into photography, the way of seeing in photography, and thus art, underwent a transformation akin to that which occurred in the arts with plein air and Impressionism.

Eva Watson Schutze, 1903 Permission: George Eastman House, International Museum of Photography and Film.

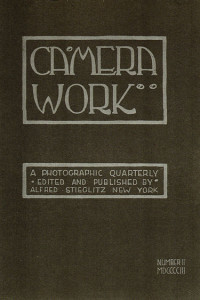

However, pictorialism represented a level of quality unsurpassed even today not just in the creation of photographic works of art and the presentation befitting them, but also in the area of the reproduction of photographic works of art of high artistic standards. In this way, pictorialism also differentiated itself from applied, commercial photography. Stieglitz’s magazine, Camera Work, appeared with a photogravure art supplement, which can be regarded as works of art similar to the original.

These art supplements also made it possible for later generations to discover elsewhere unpublished works by their great predecessors: Hill and Adamson, as well as Julia Margaret Cameron. And it is interesting to note that modernist European art, the works of Picasso, Matisse, Rodin and Picabia, were first conveyed to the American public through this periodical on photography. The articles, essays and studies published in it are also exceptionally important, as they circumstantiate the great issues of modern art and within it of the newborn art photography.

The birth of modern art photography

Here, however, is a very interesting contradiction: Stieglitz, the founder and editor of the Camera Work magazine, for a good quarter of a century strove to popularise the Photo–Secession and pictorialism, while in his own works he was always trying something different, exploring new directions.8 It was as if he had felt that pictorialism was in fact a dead-end street, because the extraordinarily high requirements it set for the creation of the photographic artwork and its artistic reproduction were not sustainable, and that manually making prints in this form could not become the “everyday common language” of art photography.

Stieglitz’s human and intellectual (editorial and artistic) greatness is demonstrated by the fact that he was the one who first presented the new photographic style in his periodical. At the end of 1916 and the beginning of the following year, he published the works of a young photographer, Paul Strand, labelling them “brutally direct” in his enthusiastic introduction. Stieglitz then closed Camera Work and his 291 Gallery at the same time, effectively putting an end to the pictorialist epoch.

With this, modern art photography in America—that is, Straight Photography, which was photo-like in every sense rather than an imitation of painting and graphic art—was born.

(Original Hungarian text published in Beszélő, 2002. June, Translated by Christopher Claris)

Notes:

- Unfortunately, we have today become so used to seeing photographs reproduced in albums and periodicals that writers on photography do not really make this distinction of principle. ↩

- Not even if art historians, curators and editors occasionally pick from photographs not created with an artistic purpose and publish the pieces they consider interesting for some reason at exhibitions and in albums. These reclassifications are in my opinion only possible – if possible at all – on very strict conditions. For instance, however aesthetic Muybridge’s pictures are, they remain pictures with a scientific and not artistic purpose; what is more they are motion pictures and not photographs. ↩

- Thus, the dilettante serious amateur and the clicking hobbyist are not the same – and this is a difference that summaries of the history of photography usually do not pay any attention to. ↩

- From our perspective this, i.e. printed reproduction as the medium, is the crux of the matter; by comparison it is of secondary importance whether the image was taken to propagate science or knowledge, fashion taste, or promote consumption, lifestyle or ideology. ↩

- The year of forming the Linked Ring Brotherhood in England. Events preceding it –from 1886 till 1891– were the writings and albums of Peter Henry Emerson, who called his photography not ’pictorialist’ but ’naturalistic.’ ↩

- In an aesthetic sense, late pictorialism after 1917 had a retrograde, restraining effect as I endeavored to demonstrate in my forthcoming article The Hungarian Paradox. One outstanding exception is the Spanish José Ortiz Echagüe, who produced a major oeuvre as a late pictorialist. ↩

- The thumbnail sketch below naturally is not intended to give a full account of pictorialism. However, to understand what I am saying, it is enough to refer to the book Alfred Stieglitz: Camera Work – The Complete Illustrations, 1903–1917 (Taschen, Cologne, 1997). ↩

- A classic example is his almost cubist picture made in 1907, The Steerage, which Stieglitz thought was his most important work as well as being his personal favourite. ↩