Miha Colner an art historian; works in expanded fields of contemporary art as an independent curator, writer and editor. Specializing in photography, video and various forms of media art he is engaged in numerous local and international projects focusing on examination, analysis and curatorial presentation of significant currents in recent art making, and therefore involved with various forms of art writing. Regularly engaged with conception and realisation of exhibitions and accompanying discursive programmes at Ljubljana-based Photon – Centre for Contemporary Photography, non-profit organisation and initiative that continuously examines and presents contemporary photographic and video practices mostly within the region of Central and Southeast Europe. As a member of DIVA (Digital Video Archive) at SCCA – Centre for Contemporary Arts Ljubljana, he works as researcher and editor of local and regional video production. In addition to editing and writing for Art-Area, biweekly radio programme on contemporary art at Radio Student, he is a regular contributor for daily newspaper and number of art magazines. Lives and works in Ljubljana.

In the era of globalization and unification of particular cultural milieus and their artistic discourses, what one could call “international style” of contemporary art, it seems that most of the local characteristics has been transformed through following dominant conventions of art making. The western world has managed to gain dominance over cultural production and to impose certain conventions that are nowadays almost inevitable in the field of contemporary culture and art. Such a conclusion leads to certain questions: Is local identity still present within a culture and if it is, is it relevant within its dominant fine art discourse?

The principal goal of this paper is to detect, research, and present tendencies of artists working in the field of photography in former Yugoslavia who have been reacting to the processes of their immediate surroundings. The latter is utterly significant on the nature of local art making. What are then main characteristics of (post) Yugoslavian cultural milieu? Is there any particular authenticity? Is there a common element that connects former republics and regions?

In Yugoslavia – as well as in the rest of the world – the field of contemporary (fine art)

photography first appeared as such in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Did Yugoslavia, for all its cultural diversity, ever manage to find its common cultural ground, specific local identity in visual arts and photography that was largely lost in 1990? Should there have been one and where is it manifested?

In the foreword of the Contemporary Art in Eastern Europe Boris Groys writes: “Is it possible to speak about Eastern European art as cultural phenomenon that crosses the borders of individual national cultures and unifies, to a certain degree, the Eastern European cultural space – being at the same time distinctive from the art in other regions? Indeed, the Eastern European cultural space is extremely heterogeneous /…/ In fact, there is only one cultural experience that unites all Eastern European countries and at the same time differentiates them from the outside world – it is the experience of Communism of the Soviet type.”[1]

However, the identity of post-communist society was mostly established and formed by the Western world: artists from Eastern Europe became aware of their position of exoticism and the Other, while, at the same time, the Western world wanted to confirm and celebrate victory over its biggest rival and enemy – communism. Hence, in a very unique way communism was demonised through this very specific art discourse supported by the western funds.[2]

However, former Yugoslav territories shared more than 70 years of common history and over 150 years of transnational ideology that is not necessary linked to their communist past alone. This common historical aspiration of transnational context enabled, to some extent, the establishment of a certain independent and specific cultural milieu. Although the identity of modern arts and culture formed in these territories usually had its roots and starting points in western cultural production, it had successfully incorporated its own local features into their overall expression.

During the period of socialist Yugoslavia (1945-1991), certain aspects of institutional and mainstream culture came out of already globalised modern media, styles and genres that are not directly linked to the language or folk tradition: i.e. rock music (punk and new wave), film (black wave), avant-garde and conceptual art, video, photography. Institutional culture and art as well as alternative and popular culture were, in fact, the only transnational elements of multicultural territory and thus (politically) extremely important for the common identity. But it seems that the common cultural milieu, at least in urban areas, was finally developed (only) in the 1980s just before the disintegration of the state.

After 1991 when Yugoslavia was finally pushed into civil war, the connections between cities and republics were completely interrupted. Hence, each of the former republics, now independent states, developed its own scene and institutional infrastructure. Curiously, although common social and cultural context was partly lost and each republic was facing very specific circumstances, the processes of social and political transformation “unified” these histories again by the end of the 1990s whilst they became almost identical over the 2000s when all newly established states adopted imparted principles of parliamentary democracy and free market economy.

Back in the 1990s, aware of recent global tendencies that they followed in their own way, a number of artists had already adopted new forms of photographic language. Their common subject was often – but not exclusively – documenting and commenting on social developments and profound changes in their immediate surroundings: often they would react to the vehement processes of political, ideological, and economical transition. Moreover, that phenomenon is so obvious in the mental and physical landscape that it is simply impossible and intolerable to ignore. In photography even the selection of motif and subject matter could strongly define local discourse.

Influenced by Berndt and Hilla Becher, Antonio Živkovič first began to develop photographic topographies in his native city Trbovlje and later expanded his interest and artistic output to the broader question of industrial decay and its heritage. Symbolically Trbovlje was one of the most important industrial and mining cities in former Yugoslavia with a strong tradition of proletarian movements. The city fell into decline radically after the aforementioned political and economical transformation.

© Antonio Zivkovic Reflection of a Memory 2001

Like the Bechers before him, Živkovič faced the quintessential story of economical and social decline: The very same processes that were happening in the Ruhr area where Bechers operated in 1960s happened in the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s. In these terms it is impossible to label his production as a mere appropriation of artistic means but rather as a reflection on the similar processes of society when entering the post-industrial era. Even so, his approach is different to that of the Bechers’ as it is impossible to find traces of the famous German objectivity in his photographs. Instead, Živkovič is very intimate, nostalgic, utterly subjective, and somewhat gloomy and melancholic.

© Bojan Salaj – Interiors III 2008

In his body of work Bojan Salaj deals with various topics of specific Slovenian local context. With the Interiors II and Interiors III series of photographs he locates and records some of the most significant symbolic places in Slovenian national history and mythology. Although he is using universal tools of landscape and interior photography, his themes are exclusively local. So although it’s impossible to understand the message without knowing the broader context beforehand, the content is entirely universal as every nation or state is glorifying its own myths and sacred places.

© Borut Krajnc – Emptiness 2004-2008

Borut Krajnc’s body of work reflects the commercialization of the cultural – urban and rural – environment. In his ongoing Emptiness series he documents the unusual moments of empty billboards in public spaces and tries to capture rare solitude and silence in between the aggressive advertisement campaigns. For Krajnc billboards represent the ultimate metaphor for present times; the fact that billboards have become an integral part of our urban and suburban landscape, all over Europe, with the situation in the former communist states being even more out of control and ruthless in this respect. Through a straight topographic approach he comments on the banality of the present time defined by the relentless usage of the public and private space for commercial purposes.

© Mojca Pungercar – Brotherhood and Unity 2006

As one of the most socially engaged artists in local context, Marija Mojca Pungerčar has been widely documenting the consequences of economical and social transition in Slovenia with projects such as Outside My Door, In Search of Closed Textile Factories in Slovenia and Brotherhood and Unity. The latter is based on found photographs taken by the artist’s father, an amateur photographer, and paired with her photographs of exactly the same locations some 40 years later. Double images are presented in matching diptychs. She focuses on the photographs of the construction of the famous Road of Brotherhood and Unity, the main traffic route in former Yugoslavia. In the 1950s and 1960s the road was initially built by young volunteers, followed by the reconstruction of the road into the highway in the 2000s built mainly by underpaid, migrant labourers from Bosnia and Herzegovina. Pungerčar depicts and compares different moments in history determined by different ideologies; she documents the same place in different periods.

© Sandra Vitaljic – Infertile Grounds (Ovcara) 2009

One of the most controversial projects dealing with the traumatic part of Croatian history is Sandra Vitaljić’s Infertile Grounds series, depicting ordinary landscapes without any visible traces of the horrific things that happened there. The artist has taken an anti-reportage stance: slowing down the image making, remaining out of the hub of action, and arriving on the spot (years) after the decisive moment.[3] Therefore the locations in the photographs are not just beautiful landscapes but sites that have gained strong symbolism due to their historical context and the fact that they have in one way or another, contributed to the formation of Croatia’s national identity.

© Darije Petkovic – Occupation in 26 Pictures 2008

In his Occupation in 26 Pictures series Darije Petković is questioning and reflecting on the processes of disintegration of the local economy by showing monumental images of present day Croatia as a representation of Zeitgeist. He closely examines, selects and documents crucial symbols of national identity, cultural heritage, and economic power and merges them into a consistent narrative. He shows façades of office buildings belonging to multi-national corporations with their aggressive advertising. As with any, economic occupation is also utterly unpleasant as the social, economic, and cultural production ceases to develop because there is no interest in investment.

© Ivan Petrovic – Vitak 1999

For the past several years, Ivan Petrović has been following and documenting situations in his immediate surroundings. His auto-curatorial project Documents brings together fragments of twelve different series of photographs representing a dynamic compilation of his intimate life as well as a view on different aspects of life in Serbia during the period 1997-2008. This photographic view is sometimes more, and sometimes less critically directed, but it always deals with futile differentiation between “collective history” and “private memory.” In both scale and consistency, this body of work strives to provide an extensive archive of the artist’s life: every-day life of students in Belgrade, scenes from his home town of Kruševac, and his unwitting two-month presence in Kosovo as a soldier in 1999.

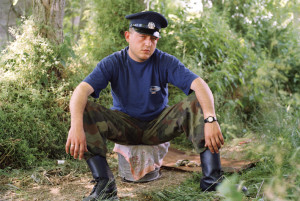

© Dusko Miljanic – Transition 2009

The thematic focus of is socially engaged thinking, specifically in relation to ecology and marginalised social groups. The consequences of transitional processes in the Balkans are still visible in the social climate and cultural landscape of Montenegro. Transition has been present for so long in the area that it has almost became commonplace. The explicitly titled Transition series is part of a wider collection that deals with processes of transformation within the Montenegrin society, a society that strives towards the capitalist system but still carries the burden of the past.

Although the artists I am presenting are all living and working in a relatively small cultural milieu, we can’t define their general approach as entirely localised as these issues can embrace very universal point of view and have global relevance. Together they represent the local (specific) and at the same time global (universal) phenomena.

For instance, Živkovič’s topographies of industrial heritage can be applied to a number of places across the world: somebody from Detroit, Birmingham, or Düsseldorf could easily identify with these images and messages. On the other hand, certain images – such as Sandra Vitaljić’s landscapes – can’t offer an immediate and clear understanding of the topic without contextualisation and interpretation. Her images documenting symbolic places of national trauma and collective oblivion and can’t immediately reveal their metaphorical complexity to the viewer without prior knowledge of the local context and history. The Infertile Grounds series reveals things that are not in the photographs and thus opens up sensitive issues drawn from recent local history by using the genre of landscape photography.

Concerning art making in former Yugoslavia, it is impossible to comprehend the messages and intentions without understanding the basic local historical narratives and occurrences. That is to say, the core of the specific local identity is hidden in it!

Borut Krajnc, born 1964 in Ljubljana; works as documentary photographer, photojournalist and an artist. He lives and works in Ljubljana, Slovenia.

Duško Miljanić, born 1975 in Tivat; an artist and photographer, and a member of the international photo group F8. He lives and works in Podgorica, Montenegro.

Darije Petković, born 1974 in Zagreb; a photographer, assistant professor in the Cinematography Department at the Academy of Dramatic Arts and artist. He lives and works in Zagreb, Croatia.

Ivan Petrović, born 1973 in Kruševac; a freelance photographer, artist, and co-founder of Centre for Photography (Belgrade). He lives and works in Belgrade, Serbia.

Marija Mojca Pungerčar, born in Novo Mesto; a visual artist who lives and works in Ljubljana, Slovenia.

Bojan Salaj, born 1964 in Ljubljana; a photographer at the National Gallery of Slovenia and an artist. He lives and works in Ljubljana, Slovenia.

Sandra Vitaljić, born 1972 in Pula; works as an artist and as associate professor at the Cinematography Department of the Academy of Dramatic Art in Zagreb, Croatia, where she lives and works.

Antonio Živkovič, born 1962 in Novo mesto; a freelance photographer an artist who lives and works in Ljubljana, Slovenia.

[1] Boris Groys, Contemporary Art in Eastern Europe, Artworld, Black Dog Publishing, 2010

[2] The most apparent example of establishing new artistic discourses through philanthropists’ funding is George Soros’ Open Society Institute and its derivative Soros Centre for Contemporary Art network (1985-1999).

[3] Charlotte Cotton, The Photograph as Contemporary Art, World of Art, Thames & Hudson, 2009