Return to the Table of Contents

Anna Rooney is the Education Program Manager of the Children’s Museum of Winston-Salem and the Co-Founder and Managing Director of Peppercorn Children’s Theatre. She holds a B.A. in Music Education from St. Cloud State University, studied Performing Arts Management at University of North Carolina School of the Arts, and is earning her M.A. in New Media and Global Education from Appalachian State University.

Thinking Strategies

Visual thinking is a valuable strategy for problem solving and communication.

Using visual thinking strategies in the arts can strengthen the communication between the artist, their collaborators, and their audience. Psychiatrist Lawrence Kubie wrote:

We do not need to be taught to think; indeed… this is something that cannot be taught. Thinking processes actually are automatic, swift, and spontaneous when allowed to proceed undisturbed by other influences. Therefore, what we need is to be educated in how not to interfere with the inherent capacity of the human mind to think. 1

By exercising the “inherent capacity of the human mind to think,” artists can develop their ability to express their vision in a way that others can understand and visualize.

Visual Thinking

For the purpose of this discussion, we will use the following definition of “art”: “the expression or application of human creative skill and imagination… producing works to be appreciated primarily for their beauty or emotional power” 2. This definition includes (but is not limited to), painting, music, graphic design, filmmaking, dance, drama, sculpture, drawing, the culinary arts, and handmade craftwork. This article will focus on the understanding of art beyond language and will not dive into the broad topic of the language arts.

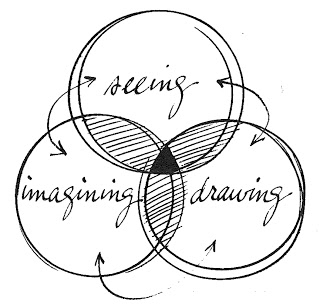

Visual thinking is almost as complicated as “art” to define, but for the purposes of this discussion, “Visual thinking is carried on by three kinds of visual imagery: (1) The kinds that we see, people see images, not things, (2) The kinds that we imagine in our mind’s eye, as when we dream, (3) The kind that we draw, doodle, sketch, or paint” 3 The word “draw” can also mean “create” when applying this visual diagram to other media.

Visual thinking is almost as complicated as “art” to define, but for the purposes of this discussion, “Visual thinking is carried on by three kinds of visual imagery: (1) The kinds that we see, people see images, not things, (2) The kinds that we imagine in our mind’s eye, as when we dream, (3) The kind that we draw, doodle, sketch, or paint” 3 The word “draw” can also mean “create” when applying this visual diagram to other media.

Where seeing and drawing intersect, seeing facilitates drawing (test this idea with this exercise: try drawing a basic image like a smiling stick figure with your eyes closed)

and drawing records seeing. Where drawing and imagining intersect, drawing communicates imagining, and imagining provides content for drawing. Where imagining and seeing intersect, imagination expands upon visual information, and seeing gives content for imaging. “The three overlapping circles symbolize the idea that visual thinking is experienced to the fullest when seeing, imagining, and drawing merge into active interplay” 4.

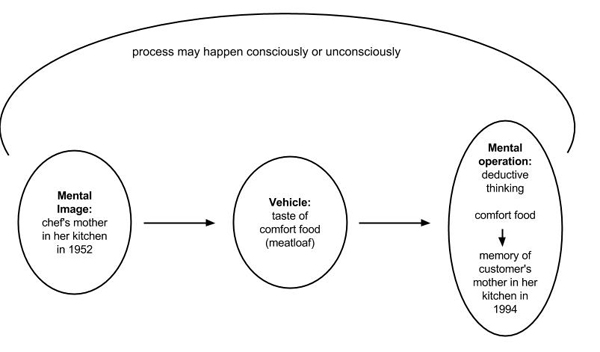

When we think, we are using vehicles to process our thought. These vehicles are not the thoughts themselves, but rather, representations of our thoughts. Artists use these vehicles of thought to communicate with their audience.

There are paintings and sculptures that portray figures, objects, actions in a more or less realistic style, but indicate that they are not to be taken at their face value. They make no sense as reports on what goes on in life on earth, but are intended primarily as symbolic vehicles of ideas… Since the picture does not simply interpret life, the beholder faces the task of telling what it symbolizes. 5

One most basic vehicle that humans use is language. When we write or speak, we are not sharing our thoughts themselves, but we are using language as a vehicle to communicate our thoughts in a way that other people can share our ideas. Language can be a very strong vehicle, but it is more inhibitive when compared to the above description of visual art as a vehicle for thinking. In the words of Humboldt 6:

“Man lives with his objects chiefly – in fact, since his feeling and acting depends on his perceptions, one may say exclusively – as language presents them to him. By the same process whereby he spins language out of his own being, he ensnares himself in it; and each language draws a magic circle round the people to which it belongs, a circle from which there is no escape save by stepping out of it into another.”

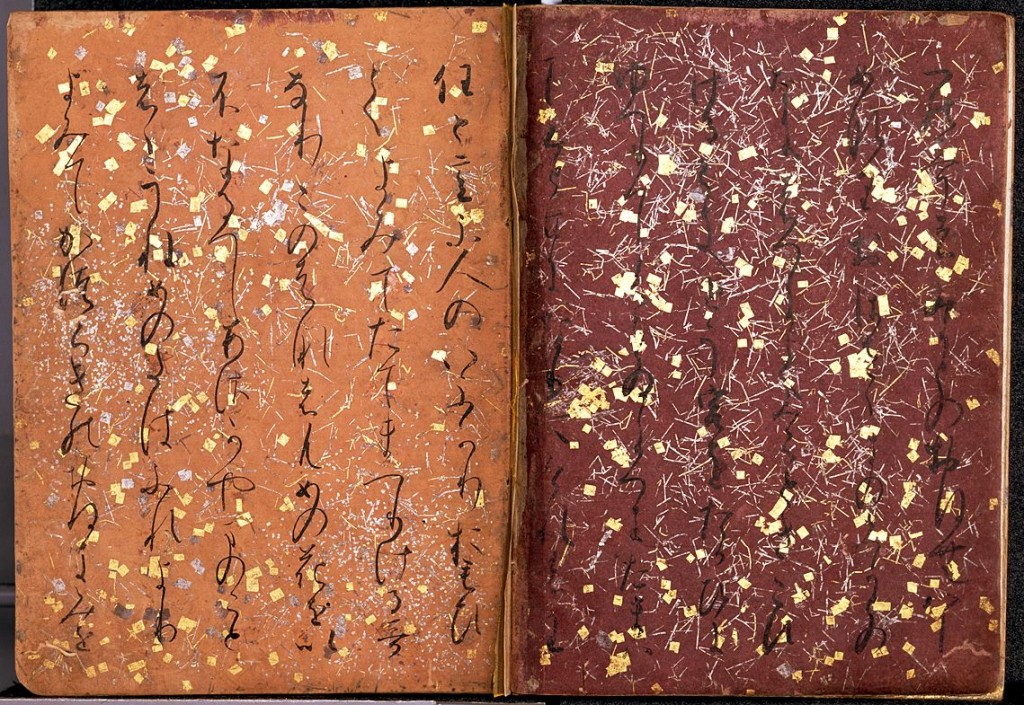

A monolingual American looking at this page of the oldest extant complete manuscript of the Kokin Wakashū poetry anthology, a national treasure of Japan, could see that the shapes of the symbols are “pretty” but cannot interpret anything about its meaning.

Collected Japanese Poems of Ancient and Modern Times

Collected Japanese Poems of Ancient and Modern Times

(古今和歌集, Kokin Wakashū), Gen’ei edition, 1120 AD. 7

In contrast, the same monolingual American might attend a presentation of art from another culture (dance, theatre, painting, sculpture, music), and some story and inspiration may be understood through non-lingual vehicles while patronizing these visual arts. These non-lingual vehicles of thought include images, photographs, moving images, sounds, drawings/sketches, mathematics, smell, touch, taste, movement, and emotions, all of which are often used as vehicles in the arts to communicate a thought or concept. These vehicles give us the imagery we need to create mental operations. These mental operations take the audience’s understanding of the original thought (transported by a vehicle of thought) and conceptualize a new thought in the mind of the audience. All this happens in various levels of our conscious thinking, including dreaming.

These vehicles of thought and mental operations are used very often, every day, by most people, and McKim wrote 8:

Visual thinking is constantly used by everybody. It directs figures on a chessboard and designs global politics on the geographical map. Two dexterous moving men steering a piano along a winding staircase think visually in an intricate sequence of lifting, shifting, and turning… An inventive housewife transforms an uninviting living room into a room for living by judiciously placing lamps and rearranging couches and chairs.

A more modern reference to visual thinking points towards a connection between visual thinking and viewing graphics on a computer, “The results are leading to a visualization movement in modern computing whereby complex computations are presented graphically, allowing for deeper insights as well as heightened abilities to communicate data and concepts” 9.

Art, Visual Thinking, and The Creative Right Brain

The skills and tools for visual thinking can be strengthened by studying the arts. Betty Edwards, the author of Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain, says “Drawing is not really very difficult. Seeing is the problem, or, to be more specific, shifting to a particular way of seeing” 10. This brings us back to McKim’s Diagram- the 3 overlapping circles of seeing, drawing, and imagining. When we both study art and practice our own art, we are “exercising” the right side of the brain and making stronger connects between our seeing, drawing, and imagining skills.

We have two sides of our brain, both important and both unique. “The left hemisphere specializes in text; the right hemisphere specializes in context… The left hemisphere analyzes the details; the right hemisphere synthesizes the big picture” 11. The current education system in 2013 in the United States of America already places great value on left-brain skills. For instance, the California STEM Learning Network holds the vision “that all students in California have the knowledge and skills needed for success in education, work and their daily lives” 12 and that they will gain these skills by studying STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics), traditionally left-brain fields. I propose that students who study these fields and can incorporate right-brained visual thinking will be the students who succeed and surpass their peers in their understanding of the concepts in their field. “Truly creative people in every field are ambidextrous- that is, capable of receiving with the left and expressing with the right” 13. These creative thinkers and learners will also grow into great teachers, able to use their right-brain skills to communicate concepts to their students from many different learning styles.

Even the field of medicine, traditionally considered a scientific field, can use creative visual thinking for stronger understanding. A team of medical residents experienced a retreat in visual thinking and these scientists with strong left-brain strategies were impressed with the results. One doctor observed, “The increased visual literacy observed through this process may be useful as the interns begin analyzing X rays, increasing their awareness about the lights and shadows that may obscure disease processes, and in the analysis of EKG’s patterns” 14. Strategies practiced in visual thinking exercises keep both sides of the brain alert, involved, and available to make better informed decisions in any discipline of learning.

Visual Thinking Skills in Action

Abigail Housen and Philip Yenawine have developed a curriculum program called VTS (Visual Thinking Strategies) that is used internationally in museums and schools. Their mission is, “VTS transforms the way students think and learn through programs based in theory and research that use discussions of visual art to significantly increase student engagement and performance” 15. Teachers ask open ended questions and neutrally facilitate discussion, while students take the lead on making observations, finding evidence for their ideas about what they see, consider the views of their classmates, and find as many interpretations as possible (as opposed to one “right” answer). VTS’s website includes testimonies from teachers around the country. Jeff Williamson, principal of Old Adobe School in Sonoma, CA, says that “Students are listening, asking questions, forming new understanding, and then talking about that understanding.” He goes on to say that the whole community at Old Adobe School, students, teachers, and parents, has been positively impacted by VTS 15.

Many artistic disciplines besides the visual arts of drawing and painting (and observing those drawing and paintings) can strengthen visual thinking skills. Andrew David Stewart, a digital music composer, often thinks of his music visually before he transcribes a piece. “I see it in my head… lines, like a staff, but not a staff. Continuous horizontal lines, not just 5 lines, but lines all the way up and down. Then the notes are moving black circles on the lines” 17. Sometimes, he says, he’s not even writing music as a form of audio artistry, but rather, the music is a way of expressing the visual patterns he sees inside his head.

Patrick Kolb, a film editor, had a similar statement. He said that when he wants to accomplish something with a video, he visualizes in his head what he wants to do and what it will look like. Especially when collaborating, he starts working with a clear outline of the specific desired result in his head so he can communicate his ideas with the other artists on the film. “But I can’t do any of that if I don’t know how to use the programs” 18. He must combine right-brain thinking (visualizing the finished product) and left-brain thinking (executing the intricacies of filmmaking software) to be successful in his field.

Developing their visual thinking strategies allows artists to translate the images inside their mind into a medium that other people can understand. The three elements of visual thinking (imagining, seeing, and drawing) identify the way we communicate with ourselves and with the people around us. By mastering our own communication styles and learning more about the learning/seeing styles of our collaborators, students, and patrons, we can build stronger connections though the work we create.

Return to the Table of Contents

References:

- McKim, 1972, p. 28 ↩

- Oxford dictionaries, 2013 ↩

- Figure 1, McKim, 1980, p. 7 ↩

- McKim, 1980, pg. 7 ↩

- Arnheim, 1969, p. 149 ↩

- Arnheim, 1969, p. 242 ↩

- Tokyo National Museum ↩

- McKim, 1980, p. 8 ↩

- Stokes, 2001 ↩

- Edwards, 1999, p. 5 ↩

- Pink, 2006, p. 20, 22 ↩

- California STEM Learning Network, 2012 ↩

- McKim, 1972, p. 23 ↩

- Reilly, Ring & Duke, 2005 ↩

- Visual Thinking Strategies, 2013 ↩

- Visual Thinking Strategies, 2013 ↩

- Stewart, 2013 ↩

- Kolb, 2013 ↩