T Vásquez is an artist using the medium of photography and video to explore all aspects within the creative process. She is presently a candidate at the University of Nevada Master of Fine Arts program.

“It is no longer a matter of starting with a “blank slate” or creating meaning on the basis of virgin material but of finding a means of insertion into the innumerable flows of production.”

Nicolas Bourriaud

Photography’s innumerable flow of production in relation to Bourraiud’s quote is more important of today than when the quote was written. Twenty years ago the conversation about photography and computer technology was not aligned as today. From its inception, photography has impacted the world and now with computer technology the world cannot separate the two. As the history of photography has demonstrated with each new development in the medium, this opens another connection for creativity. In speaking with Nate Larson and Marni Shindelman, both photographers collaborate in using photography and computers with online social networking to create bodies of work. Their use of the social networking platform Twitter, specifically the location metadata (longitude and latitude coordinates) from people’s tweets, begins their research. They travel to the locations and photograph the specific areas. In questioning, their research and process was to open the conversation into their collaboration and to discuss the twenty-year progression of photography and computer technology in art.

Then the Computer…

Artnews’ 1993 February issue had an article titled “Art Goes Hitech” by Mark Dery1. The article gave an enlightening view of how computer technology and the world in art joined. It covered the innovations in art at the time and how computers, computer software programs, and peripherals were being used, also how artists were incorporating these new tools with their respective mediums. However, photographers were having hesitations because of the reluctance to computers. “Ed Hill and Suzanne Bloom – a husband and wife team who collaborate under the name MANUAL – see the wedding of camera and computer as a fruitful union, although they acknowledge that many artists see it as a marriage of monsters.”2 By 1993, traditional photography came into its own as an art form. The art world had come to recognize the expressive language in making an image with a camera. In making this even more relatable, the market for the medium was active. The introduction of the new tools – a CRT (cathode ray tube) monitor, a CPU (central processing unit), computer software programs (Macromedia (animation and graphics), Quark (page layout), and later Adobe) and a printer – meant new layers of learning and integration. Photographers had to buy another piece of equipment and then learn how to manipulate the new tools at the same time. “The computer represents a threat to the traditions of subjective expression in the same way the camera did 150 years ago,” says Hill.2 During this period, subjective expression meant was the artwork generated solely from the computer or was the artist hand involved? The other notion of subjective expression, were these new tools going to compete with photography’s ever lingering question – is photography art? Hence, the despondent reluctance to computer technology; photographers would have to individually find a methodology to relate the idea of computer technology. Photographers had to understand how to make the traditional processes work and apply the processes to the computer software programs and the interpolation with printers. This meant dogging and burning in the traditional darkroom needed to be translated in the digital darkroom using computer software programs. One hoped this would be a smooth transition, yet the transition would take time for photography and computer technology to come together. In the early 2000s, the integration with computers became a common adjustment because the technological advances with computers were readily available in the culture overall. Photographers were beginning to adapt and make connections with the relationship of the medium and the new tools. The other advantage during this time was computer technology industries were engaging with the art world; specifically, the advances with computer software programs and peripherals improved. The ability to use photography and computer software programs came together through Adobe Photoshop 5.0; as the number indicates, the series evolved greatly, but by the time Photoshop 5.0 came on the market in May 1998, the connection had equated.

Put to Rest…

In 1999, six years had passed, photography and computer technology were becoming integrated in the art world, nevertheless, photographers were still reluctant. Artnews in the February issue of the same year did not just publish an article; its cover summed up the overall theme of the issue “Photography’s Great Debate Traditionalist vs. Postmodernist.”4 One article titled “Photography’s Great Divide” a question and answer interview with Artnews’ executive editor Robin Cembaltest with Photography Department Curator Peter Galassi at the Modern Art Museum in New York City. The conversation evolved around photography and the traditions in painting and how the traditions in painting found its way into photography. The conversation eventually centered around two artists Diane Arbus and Cindy Sherman:

“If Sherman was an artist who used photography, what was Diane Arbus? The art world had at last come to embrace photography as art, but instead of bringing new recognition to photography’s artistic traditions, this development only reinforce the old distinction between “art” and “photography,” to the continued detriment of photography.” That remained true, even as interest in traditional photography began to grow.”5

Galassi commented that this distinction was due to the market. 6 The question of art and photography, especially pertaining today with the integration of computers and online activity with social networking, is not to divide. It is to elevate the possibility of the connections of the medium with the tools. As Galassi questioned, “What was Diane Arbus?” Arbus’ traditional photograph method opened the possibility for all who came after her to explore all aspects of humanity in regards to the human condition. The exploration now includes photography with computer technology, so the question becomes what to do with the information in relation to the creative process? “Artist today program forms more than they compose them: rather than transfigure a raw element (blank canvas, clay, etc.), they remix available forms and make use of the data.”6 In pondering, the notion of reproduction or post-production through remixing, Photographers today connect the information as they navigate their own creative journey. As Larson states, “For years I have been making work about religious miracles and doing a lot of Internet research and tracking these things down. Marni was making work about Internet legends where she would find these stories online and this would inspire her to make new photographs, so when we started working together we were talking a lot about the Internet and a lot about the connectivity and talking about the idea of storytelling, because both of us were telling other people’s stories in a certain way. We are looking at these little bits of data and memorializing these stories in color photographs and we are standing on the sights that the person stood on.” Larson and Shindelman images evoke a journey into another person’s world, not in a voyeuristic intrusion. We know someone was at the location base on the words. The viewer is left to reinterpret a scene base on the information given. This is art. In referencing, Sherman and Arbus are to bring forward the methods used by these two photographers.

Image and Location

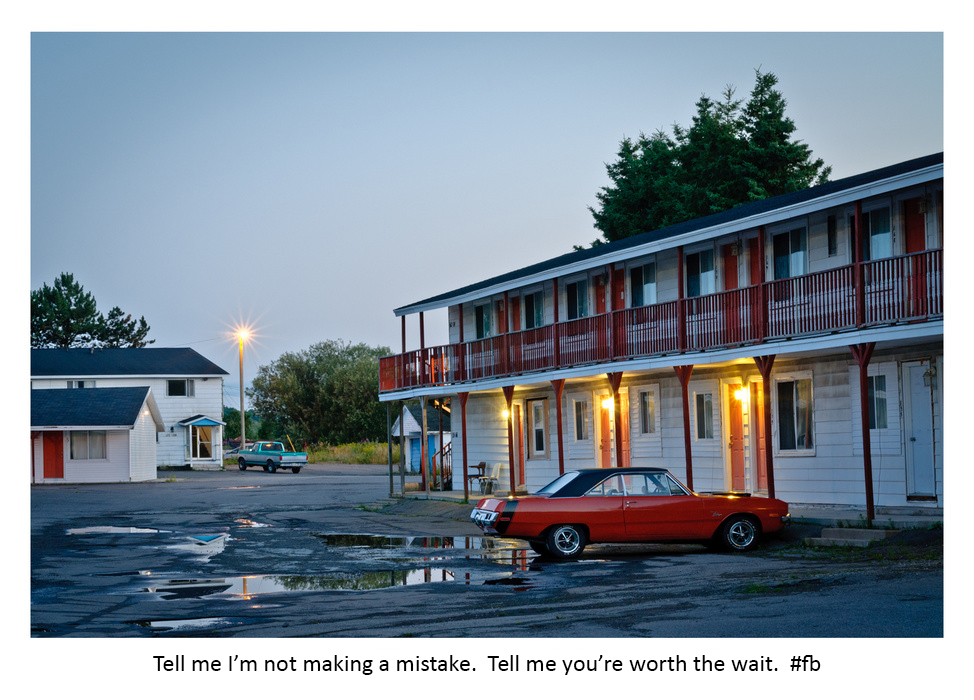

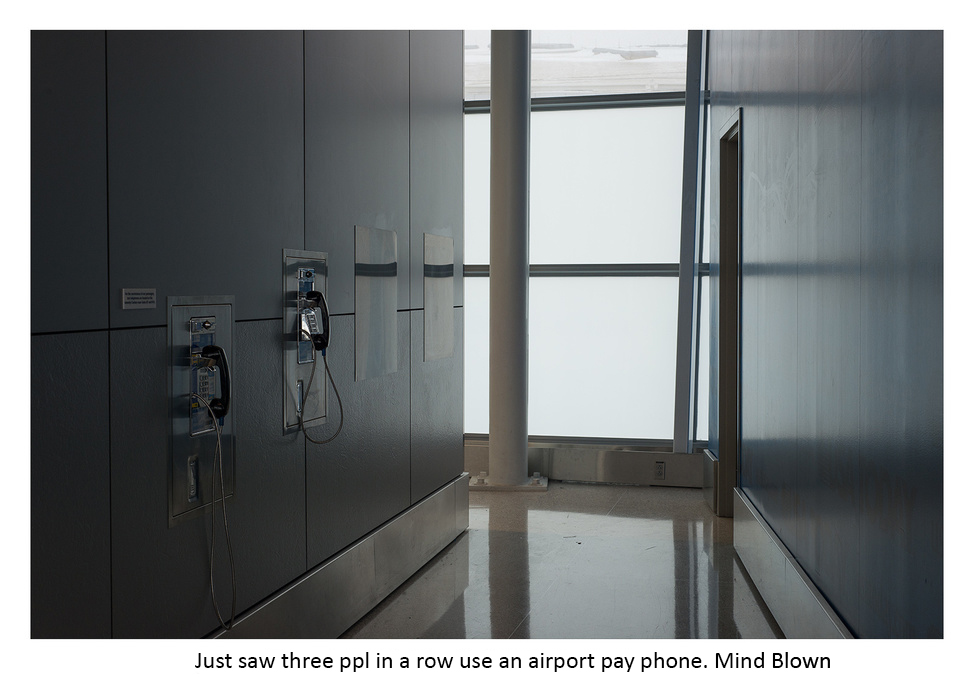

The global positioning system that generates the longitude and latitude coordinates for a tweet aid Larson and Shindelman in finding and creating photographs. The text from the tweet and the hashtag functions as the title of the finished image. “Tell me I’m not making a mistake. Tell me you’re worth the wait. #fb.” This photograph is part of the Maritime series from August 2011 at Saint John, New Brunswick. A lone red car with black trim and rag top parked in front of what looks to be a roadside motel also trimmed in red railing with white side paneling reads the sobering loneliness with the text. Another tweet, “Well that made me happy #secretcrush shhh lol (laugh-out-loud)” from the Atlanta series from June 2012 in Atlanta, Georgia reads differently with a lighter tone in repeated elements of windows and taupe side paneling framed by the green leaves of the trees. These images present a logical order of wanting to know who sent the tweets. This is part of the invitation of wanting to identify the place and the words. The storytelling begins with the tweet but the story does not end with the photograph. The maker of the message is significant in the participation of the Geolocations series, along with the audience. “These tweets have my location” is an image of orange groves from the Desertscapes series from August 2011 in Palm Desert, California. The image is customary of the series; however, the text extends the realization of how quickly the meaning changes the image to an elevated interest. “I just saw three ppl (people) in a row use an Airport pay phone. Mind Blown.” The image of two public pay phones at the Indianapolis International Airport in Minnesota in June 2013 (This image was also part of an installation series at the airport) places emphasis with place. The notion of sitting and watching a person making a call on public phone seems average enough, yet it is not in keeping with today’s telephone mobility. The text again adds meaning by transfixing the past with the present. The technology of yesterday is contributing with the technology of today in a cyclical evolution for what is to come of the future. These four images and four tweets are also a part of the video segment.

Of the Culture

During the late 1990s and early 2000s photography and computer technology were finding a better arrangement in the educational community. Throughout this time, Nate Larson8 and Marni Shindelman9 were respectfully pursuing their educational endeavors in photography. Larson and Shindelman realized the importance of the tools, though they would have to wait a few more years to find the exact fit and how to smoothly incorporate the photographic methods with computer technology. In finding a connection with photography and computers, along with social networking platforms was to ensure a consistent approach between research and process. Larson and Shindelman use of social networking relates with Bourriaud’s statement: “To rewrite modernity is the historical task of this early twenty-first century: not to start at zero or find oneself encumbered by the storehouse of history, but to inventory and select, to use and download.” 10 The statement establishes the global culture of our time. How do we use the information that is downloaded with visual information? Also finding the answers with the common threads with visual information and art, this is the task of artist today. Larson and Shindelman photographs are locality specific. The Twitter connection has taken them across the United States and the United Kingdom. Larson and Shindelman are not married to each other; however, they found a collaborative bond through their individual work. Nate Larson’s «earlier work dissects the role of belief in contemporary American culture through the eyes of religion and paraspeculative events.» Marni Schindelman’s earlier «work explored localities that influenced her connections of childhood memories or events that drew personal interests and speculation.» Shindelman’s take on their collaboration: “We met because we were both working on myths and legends. I have been working on the Internet for about seven or eight years at that point and Nate has been working on miracles and other worldly things. We kind of combine those two things. I still think you give an idea to the collaborative and keep it for yourself and everything overlaps.” Larson and Shindelman found a way through collaboration to make photography and computer technology merge. The research in finding locations and sifting through data online within each photographer’s vicinity gave them more opportunity to incorporate the medium. These two photographers are not taking sides on methods. These two photographers are conceptually connecting photography with the information of today’s culture.

Twenty years have passed since the Artnews articles. In mentioning these articles in relation to the hegemonic computer technology driven world of today is to show the tolerance and manner of the art world of the past, and to expand photography and computer technology evolvement in the art world. Photography will always be a part of the innovative connection to the world. In writing this piece, there is still a small minority who will object to photography’s place in art. Those voices will not change. The subjective expression pertaining to photography today needs to continue examining the cultural connection that is taking place with computer technology and, specifically, online interaction. Lastly, Peter Galassi was asked about photography’s détente11 his reply, “It has already begun to happen.”12 Nate Larson and Marni Shindelman are examples of the détente of this period. As you view the video on this webpage, you also are experiencing the détente of photography and computer technology.

On Video: A Conversation with Nate Larson and Marni Shindelman

The video is an opportunity in providing the viewer to have a visual connection by hearing both artists speak via Skype and to view some of the images from the Geolocations project. The project can also be viewed at Larson & Shindelman.

- Dery, M. (1993) Art Goes High Tech. Artnews 92 (2), pp.74-83 ↩

- Ibid, p.75 ↩

- Ibid, p.75 ↩

- Cembalest, R. (1999) Photography’s Great Divide. Artnews 98, pp.86-89 ↩

- Ibid. p.87 ↩

- Ibid, p.87 ↩

- Ibid, p.87 ↩

- Nate Larson is currently teaching photography at Maryland Institute College of Art Nate Larson ↩

- Marni Shindelman is currently teaching photography at the University of Georgia, Lamar Dodd School of Art Marni Shindelman ↩

- Bourriaud, N. (2002) Post-Production: Culture as Screenplay: How Art Reprograms the World. New York, NY: Lukas & Sternberg. p. 93 ↩

- from French Relaxation ↩

- Cembalest (1999), p. 88 ↩