Return to the table of contents

Roberto Muffoletto is the founder and director of VASA and editor of VJIC. He holds an MFA from SUNY Buffalo/Visual Studies Workshop, and a Ph.D. from the University of Wisconsin at Madison. He is past editor of Camera Lucida and Frame|Work.

Rule #1 1994 : If you do not want it copied don’t put it up on the Internet.

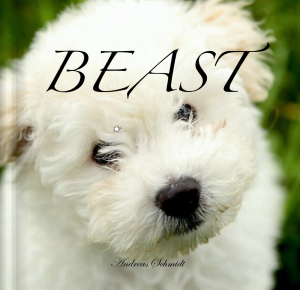

Beast book cover

Beast (2011) as a book is a collection of dog images copied from Facebook. Is a warning cry by Andreas Schmidt to be aware that your images and text are subject to appropriation by anyone. (All Beast images are with permission.)

With just a “right click,” video, audio, and image files may be downloaded to a user’s hard drive. With a “click” and “drag,” text may be copied to other documents. Music and video file sharing is common across the “net.” Questions of ownership and copyright are of major concern not only for individuals but for profit-making institutions who sell access to material under their control as well. For example, Getty Images, and The International Center for Photography and Magnum.

Long before the Internet, there were concerns over the ownership and rights of authors, regarding both text and image. Concerns over protecting one’s creative and intellectual property are found before the 1800s (in the United States) with the first copyright laws appearing in America before 1783 and the American congress passing the Copyright Act of 1790. Jump now to 2013 and the digitalization of texts and countless media files accessible on the Internet. Files are being downloaded without regard to copyright laws and a disregard for intellectual and creative ownership. The concern over creative and intellectual ownership of images and texts found on the Internet mirrors the copyright issues of paper-based image and text platforms, but with a different intensity. For example, it has been suggested by The Q&A Wiki answers (http://wiki.answers.com) that an estimated 230 million songs are illegally downloaded per day off of the Internet per day.1 Add to that, as reported on Quora, there are an estimated 200 hundred million photographs being uploaded to Facebook every day, or six billion per month, making Facebook the largest photo archive on the Internet. Each Facebook page/user, depending on his or her public/private settings may attempt to control accessibility to his or her images and exchanges by making them public or private.2

Instagram logo copied from a Google search, 24 September 2013.

The “net” raises other questions as well, issues related to “public” and the “private” virtual spaces. With platforms such as Facebook, Flickr, YouTube, Instagram, and others allowing, in most cases, the display and dissemination/consumption of moving and still images, questions and concerns over copyright and aesthetic and creative ownership become a more pressing issue.3

Facebook logo copied from Google search, 24 September 2013

Add to this mix of issues related to ownership and the protection of private and creative works of art is the notion of “appropriation.” Appropriation may be understood as “a method of artistic transformation of found materials – historical or contemporary – from all areas of life. … This is accompanied in all cases by decontexualization followed by a recontextualization of the original material. … with the aim of contents of the past into statements relevant to the present and creating one’s own “original” artworks.”4

Andreas Schmidt is a London based artist, who over the last few years has created books challenging the notion of copyright and privacy on the Internet by using the images and texts of others found on the net as the content to his work, and he, himself, claiming copyright of the book as a constructed transformation, his voice.

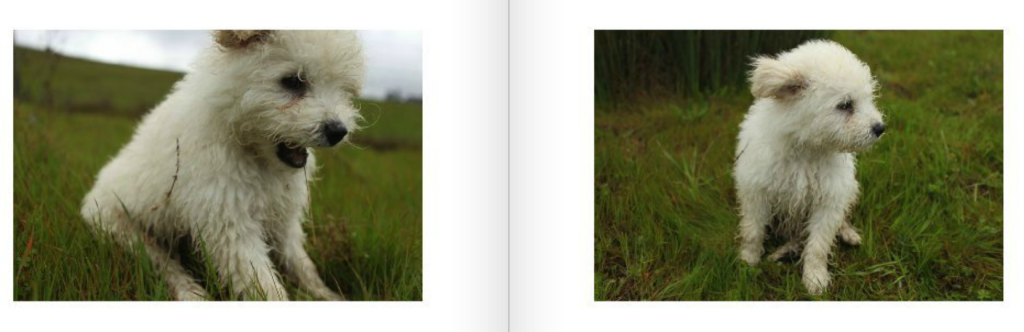

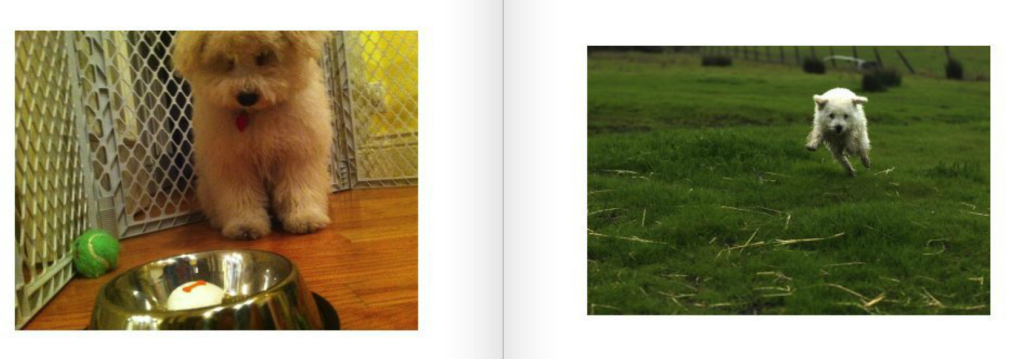

The artist appropriates images and text from social networking platforms, mainly Facebook. Andreas Schmidt then downloads and recontextualizes them in to physical books. His work is published and sold on the Blurb platform (blurb.com). It is important to realize that the copied work existed originally in a virtual public-private space — Facebook. Normally to access photographs in Facebook the owner of the page has to make her page “public” or “private” (private being open to approved or invited friends). After accessing the pages and images in Facebook, Andreas downloads, creates his sequence and structure, and then uploads the images to Blurb’s web site, producing his book, a creative form re-presenting and transforming the tangential meaning of the taken images. This is an important point to consider. It is in the reorganization of the book’s objects – in the case of Beast the objects are images – appropriated for use as an expressive and creative event.

Is Andreas taking the public or privately (private in the sense that he downloaded then – took them – from membership based sites) intended works, in a sense “stealing” them, or is he working within a tradition of appropriation where artist may, for profit or not, claim the final form as the artist’s own, his own? The answer to that questions lies with the owner of the images and the courts. The courts in the United States and in Germany have passed decisions allowing for the appropriation of images/objects for use by artist in making an expressive statement. If you are the owner, you may shout foul, but it may get you nowhere. As I will refer to later, the book is of no real consequence, but the question of appropriation, the form constructed by the artist, is.

From Beast

The book created by Schmidt is entitled “Beast”5 is a collection of over 65 sequenced images copied from a Facebook site belonging to Mark Zukerberg, the founder of Facebook. The dog, named Puli, is owned by Zukerberg. (You may access the page here, you do not need a Facebook account.) Nowhere in the book is notice or credit given to Zukerberg and the Facebook site. Andreas does mention the source of the images in the “about the book” information statement on the Blurb site:

Beast, by Andreas Schmidt, is a beautiful book of beautiful pictures of a beautiful dog. Our hearts are touched by numerous and humorous pictures of the cute little creature as the dog is bathed, at play, learning about the world, and more than often, performing for the camera. All is well until we realize that this is one of the most famous dogs in the world, liked by 448,324 people. Beast is, of course, none other than Mark Zuckerberg’s dog.

From Beast

Andreas copyright’s his book with the following statement:

From Beast

The author, Andreas Schmidt retains “sole copyright to his or her contributions to this book.” Interestingly enough, the copyright notice does not explicitly state that the copyright includes the images, but only the contributions of the author’s in making the book. Schmidt uses another person’s creative property to make his own creative work, something that we all do in various ways.

Andreas is up to more than just appropriating the work of others, but is raising the issue of ownership and copyright in the age of the Internet and global accessibility, distribution, and consumption. As stated in his Beast promotional page in Blurb:

“Andreas Schmidt downloaded all images contained in the book from the Beast‘s very own Facebook page. Publishing these images, which are readily available and shared on Facebook and on the web in an even greater public domain as a book is both an experiment and a warning to us all. The question we have to ask ourselves is: Does this book not teach us in the most powerful way that, no matter how innocent the pictures are and how wonderful it appears to be sharing your photographs with everyone world-wide, you never know who is looking and who might be using your pictures to their own advantage?”6

In a private email correspondence (now made public with this publication) with Andreas, he pointed out that he did not know Mark Zuckerberg or did he seek permission to use the images in his book. Andreas also noted his intentions in that “the book raises important questions about copyright and privacy issues in the current age of social networking and the web, and without it existing as a physical book, those questions would not be addressed as they are.” He continues with saying that “Appropriating photographs as a strategy to make new art work has been around for a while. What is a relatively a new phenomena, however, is that more and more artists are using images found and sourced on the Internet to make new work. As an artist, I consider it to be my human right, equal to freedom of speech, to do exactly that. Within the frame-work of “fair-usage”, I have adopted Zuckerberg’s images and created a new art-work, an artist’s book, and of course I will sell this at a profit.” As of the 30th of June, 2013, Andreas has made a profit of £11.05.7

Andreas, in his book statement, invites us to consider the use of social media, where everything is public/private and may be copied and used by others as part of their creative process.

The book Beast is presented as a work of art by an artist. It is a critique, not of the images or of Mark Zukerberg (or others presented in the book), but of the display and accessibility of images (and text) on the Internet and specifically on social media platforms. Being a critique, a critical reflective comment does his work fall under “fair use”? It is important to note that nowhere in the book does Andreas reveal his intentions. Unless you read the Blurb information or knew of his other works, the reader could leave the text thinking it was just a book of cute dog photographs. Does the author have the responsibility of informing the reader somewhere in the book, in some manner, of his intentions? For example, the work of Tom Forsythe and his treatment of the Barbie doll (see below) is an obvious comment on the constructed Barbie world, whereas, in Beast there is no obvious comment or treatment of the content to inform the reader of Andreas’ position on your potential loss of privacy. What is the responsibility of the author to his reader and to his art?

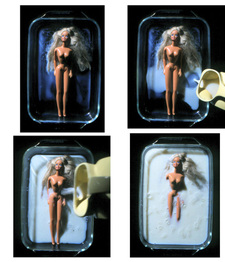

© Tom Forsythe, from Malted Barbie, copied without permission from a Google search

On the issue of Fair Use the “first factor is regarding whether the use in question helps fulfill the intention of copyright law to stimulate creativity for the enrichment of the general public, or whether it aims to only “supersede the objects” of the original for reasons of personal profit. To justify the use as fair, one must demonstrate how it either advances knowledge or the progress of the arts through the addition of something new. A key consideration is the extent to which the use is interpreted as transformative, as opposed to merely derivative.”8

Two examples of court decisions are on fair use:9 “When Tom Forsythe appropriated Barbie dolls for his photography project “Food Chain Barbie” (depicting several copies of the doll naked and disheveled and about to be baked in an oven, blended in a food mixer, and the like), Mattel lost its claims of copyright and trademark infringement against him because his work effectively parodies Barbie and the values she represents. When Jeff Koons tried to justify his appropriation of Art Rogers’ photograph “Puppies” in his sculpture “String of Puppies” with the same parody defense, he lost because his work was not presented as a parody of Rogers’ photograph in particular, but of society at large, which was deemed insufficiently justificatory.”

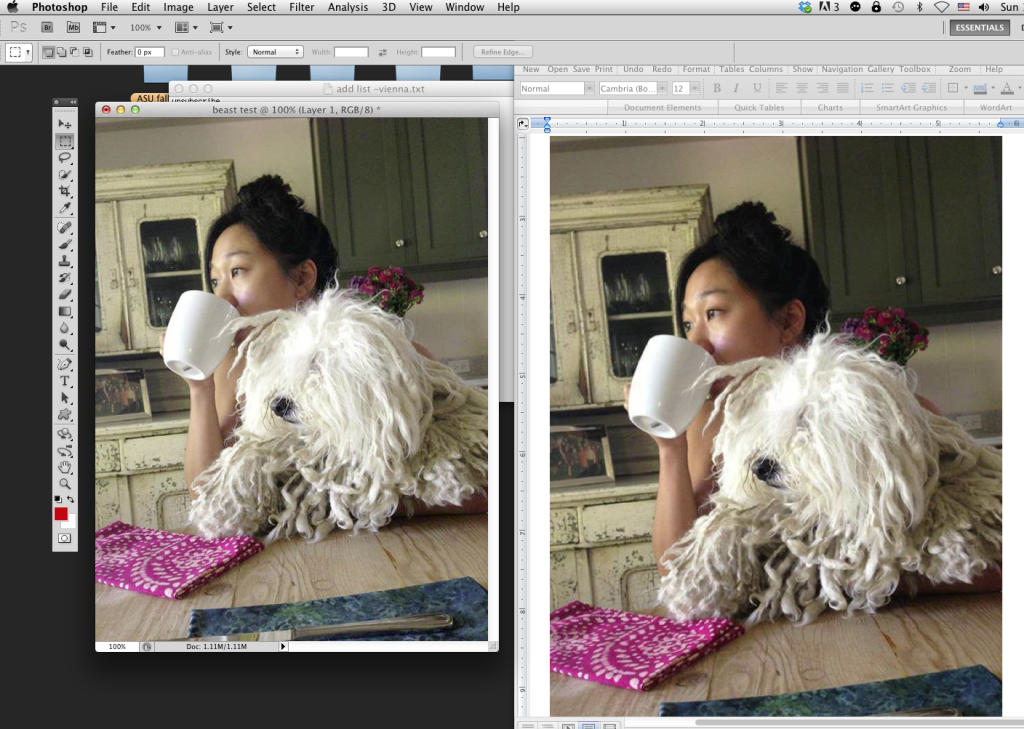

This image is not in “Beast” but is copied from Facebook and manipulated in Photoshop by the author of this text. It is meant to demonstrate the ease of downloading and manipulating an image from Facebook.

The work of Andreas Schmidt, as exemplified by his published book Beast, is it a parody, if so of “of what and how”? With the examples cited above, would the book pass the “parody” test? Is simply using someone else’s work to make a statement concerning the Internet an infringement of the copyright law? Is it enough that the author created, in this case, a physical book for sale, attempting to draw attention to issues of ownership in the digital networked age. Does the book address copyright and ownership? If so how? Is the book itself a parody?

A recent posting titled “Second Circuit Court victory for Richard Prince and Appropriation Art” in the Stanford University Cyberlaw Blog by By Julie Ahrens. (April 25, 2013 at 6:12 pm) references the copyright the case of “Prince versus Cariou.” Ahrens in her post notes that the second circuit court decision in favor of an artist right to appropriate works of art into his or her own work of art.

“Today the Second Circuit Court of Appeals issued a long-awaited decision in favor of fair use in Cariou v. Prince. Reversing the district court’s finding of infringement, the Court held that Richard Prince’s use of Patrick Cariou’s photographs in 25 of his 30 Canal Series paintings was a fair use. The decision affirms an important tradition in modern art that relies on the appropriation of existing images to create highly expressive works with new meaning. The decision confirms the principle that a use can be fair even if it doesn’t criticize or comment on the original work. While it it’s far from groundbreaking to say that commentary or criticism isn’t necessary for fair use, it is a principle that hasn’t been applied before in the visual art context. Here the Court held that copyrighted images can be used as raw material to create new works of art, even where the artist had nothing to say about the images he relied upon. Transformation can be found where the artist’s expression and composition, presentation, scale, color palette, and media are fundamentally different and new compared to the photographs.”

Does a person have the right of expectancy in publishing their family images, holiday trip to the sea, or their Friday night party on the Internet an expectancy of privacy and ownership, or is it as Andreas argues, his right as an artist to use anything and everything in the creation of his artwork?10

Andreas argues, the placement of the unaltered images in Beast into a sequenced book, become a new work of art. This is where the book fails. I am not going to argue the artistic merit of the book, for, after all, it is a book of cute dog pictures. If the author’s intention was to wake us up to issues related to ownership and pirating on the Internet, it falls short. The only place where the reader may gain a sense of those issues is if they read the text located on the Blub site. In the book itself, there is no mention of the image sources or the fact that they were lifted from a Facebook site, but this was done to demonstrate to the reader that his or her work is not safe and that he or she has lost control of his or her images. As Andreas states, the book is “a warning to us all,” but there is no indication of this. For the unsuspecting reader who picks the book up, the warning is never sounded. For the warning to be heard, Paul Revere had to shout his message of warning.11 Andreas never rings the bell and he never warns us: we just get cute dog pictures.

Rule #1 2013 : If you do not want it copied don’t put it up on the Internet.

Return to the table of contents

Title: Beast

Author: Andreas Schmidt

Self-published in Blurb

Copyright 2011

- See rough projections at Wiki Answers Q: How many songs are illegally downloaded per year ↩

- The concept of private may be misleading in Facebook because the member gives Facebook rights to their images and texts. ↩

- Digital Civil Rights in Europe: German court decides Google’s image search does not infringe copyright and The OPKat: BGH: Google’s image search is no copyright infringement ↩

- Noll, Petra, in “aneignung, appropriation”. Published by Fotogallerie Wien, 2012. p. 13 ↩

- Self-published in Blurb, in 2011 ↩

- BEAST by Andreas Schmidt: Fine Art | Blurb Books UK ↩

- Private email exchange, 30, June 2013 ↩

- Copied from Fair use – Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia, August 25, 2013. ↩

- Copied from Fair use (Fair use under United States law) – Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia August 25, 2013 ↩

- Over the years we have witnessed the media using images found on the net to accompany their posts. Photographs of personalities and private individuals seem fair game to the news media and to others. ↩

- Paul Revere made his famous ride to warn the American colonist that the British army was marching their way. See Wikipedia: Paul Revere and History: Paul Revere ↩