Return to the Table of Contents

Natalya Reznik is a photographer and art-historian. She works as a scientific editor of a Russian website dedicated to contemporary photography: Photographer.ru. She studied design at Perm State Technical University and earned a PhD in philosophy of culture in Saint- Petersburg State University. Currently she is a researcher at University of Erlangen-Nuremberg (Germany), writes her thesis in the field of theory and history of photography and makes personal photo projects. Natalya is a regular contributor to VJIC.

It was at an exhibition of photo collections at Les Rencontres d’Arles festival, where I first discovered the book “The Mark of Abel” by Lydia Panas. I did not have the time to read the text inside the book and therefore, I was unsure of the people in the portraits. But these photographs drew my attention at first sight — something elusive and mysterious resonated from the faces, which were partly blurred with the help of tilt-shift lens. They looked timeless and full of existential meaning. It was hard to look away.

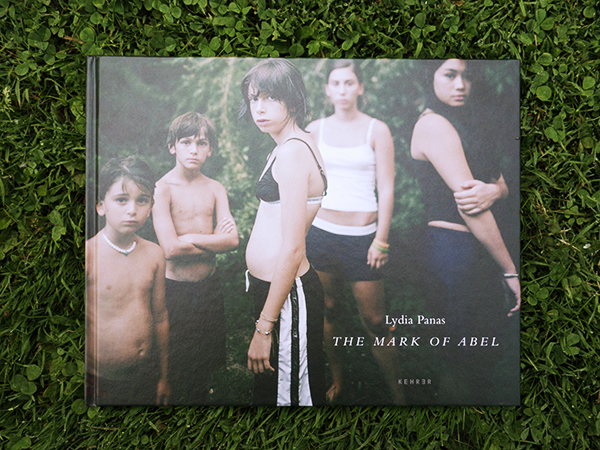

The book “The Mark of Abel” by Lydia Panas

I had the same feeling, perhaps even stronger, while recently at a vernissage in Eduard Planting gallery in Amsterdam, where the project «The Mark of Abel» was presented. It seemed like a kind of protective field was created between myself and the people in the portraits. The faces did not allow anyone to cross the border and «enter» their territory. It was as if a person was unable to come closer than what the faces allow. After all, a viewer is an outsider, a stranger, whereas they are connected by blood. They are a family.

The photo from a project “The Mark of Abel” by Lydia Panas

A hard-cover album consists of A4 size colour photographs with white margins. The format of the book is similar to the size of a traditional family album. Similarly, the book is actually filled with family photos. Nevertheless, Lydia’s approach to making of family portraits is far from a classical one. All the photos have been made in Panas’s own backyard, where she usually shoots using a large format (4 x 5”) camera.

The photo from a project “The Mark of Abel” by Lydia Panas

The project started with an accidental photo shooting experience of Lydia’s own children and relatives. Afterwards, inspired by the result, she invited friends, friends of friends to participate.

In every weather and season, people pose for family portraits without any special preparation for shooting, as if they were just passing by accidentally.

The photo from a project “The Mark of Abel” by Lydia Panas

The people in the portraits look very innate and organic in a natural jungle, which reminds me of Eden. Some of them have moist hair as if after summer rain. Or as if they just emerged from an ocean, or from a mother’s womb. Sometimes their figures almost dissolve into the natural environment. Born by nature — they blend with it, becoming a single piece, which seems especially important for the author. Indeed those photos show no signs of civilisation. One cannot tell who the people are, where they work, what they are interested in, which social group they belong to, and so on. They look very much at ease, with no social masks or borders. It is as if Lydia washed away all the social signs, decontextualized her models, and turned them into modern Adams and Eves. They became the free children of Eden, who appear from and leave to nowhere. It is only blood – a natural connection between them- that is important.

The first photograph in the book depicts water, an ocean. Time and stream of life, which gives birth to all the things and takes all the things away (was it the ocean where these people got their hair wet from?).

The photo from a project “The Mark of Abel” by Lydia Panas

Unexpectedly, a teenager girl on the cover of the book, whose belly is pushed out, immediately refers to a theme of motherhood. A symbol of birth appears many times in the book. Two middle-aged women stay side by side in black dresses and embrace their bellies. Their hand gestures look far from accidental as well. Other shots show an adult daughter standing near her mother. By looking at the mother’s figure, one can be sure that she is pregnant.

The photo from a project “The Mark of Abel” by Lydia Panas

The next is a portrait of a young couple. A girl, who was the same age as the daughter from the former photo, has a chin piercing and wears a wedding dress. She looks at the lens with a sad and slightly confused look. In her eyes, one can see a shade of anxiety and a feeling which appears in the eyes of a person whose destiny was suddenly revealed to him/her. Artificial traditional flowers on her slightly old-fashioned wedding dress (which probably belonged to her mother) match with flowering white bushes behind her. The flowers are a reminder of a time of bloom and fertility.

The photo from a project “The Mark of Abel” by Lydia Panas

The topic of motherhood is finished by a dark-haired teenager girl who is photographed in front of a pond. In her arms she holds a dark towel as if it was a newborn child wrapped in a blanket offered to a viewer. Gravity, calmness, and with a kind of resignation in her eyes, her pose, and even some of her features, look similar to Sistine Madonna, carrying her child to people, ready to sacrifice it for people.

A hardly verbalised feeling occurs somewhere in between photographs with pauses, in combination of shots, in cross rhymed ideas and visual images. In the same manner, unique family features can only be identified by comparing facial features among family members.

The photo from a project “The Mark of Abel” by Lydia Panas

Turning the pages over and over again, I cannot stop thinking why some images look very dramatic, while there is no allusion to drama. Suddenly, while looking at the photograph with three differently aged women (about forty, fifty and seventy five years old, likely to be two sisters and their mother), I realized it seems as if we were looking at the same person, but in different periods of life. Due to subtle similarities in facial features, one can feel that it is all about one and the same person — merely altered by the flow of time. Thus, Panas manages to show time in photography without using traditional approaches (e.g. a sequence of portraits of the same person taken with different intervals of time). Instead she depicts time in a single shot. This method unwittingly makes one think about the life-cycle, and thus, the book itself turns into a visual parable about birth, adulthood, life-giving, decay, and death.

A tattoo on the arm of Lydia’s teenage son visually matches with shed leaves on the ground and almost merges with them (is not it the so called «mark of Abel»?) Growth, maturing, and decay are inseparable from each other.

The photo from a project “The Mark of Abel” by Lydia Panas

The last image in the book is a portrait of the long-haired teenager in white church clothes. He looks like a silent angel. He is about to turn around as if called by somebody invisible. His clothes dissolve on white snow. The next shot shows only bare tree branches and the plain covered by snow.

The photo from a project “The Mark of Abel” by Lydia Panas

The Mark of Abel

photographs by Lidia Panas

Texts by Maile Meloy, George Slade and Lydia Panas

96 Pages

52 Colour Photographs

Hardcover

Publisher: Kehrer Verlag, Germany