Return to the Table of Contents

Olof Jonsson is a PhD in the Department of Education, Uppsala University, Sweden. Literacy, reading tradition, and how images and text, intertwined, convey a message to the reader and the relation between them for visual rhetoric and pedagogical action have been a major part of his research. His latest publications are Skolplanschen. Argument i spänning mellan bild och text, perspektiv och kontext. (2007 ) Lic. Uppsala universitet; Skolplanschernas historia. (2008) Essay Vägval, FSUH. Föreningen för svensk undervisningshistoria; Bilden och texten: En studie av ljusets och seendets pedagogik (2010) Diss. Uppsala universitet.

From Educational Chamber to Lecture Room

In the Swedish educational system, Churches and Schools have had a long common

history. With the Reformation and the years from 1520 to 1686 came the requirement for the masters to teach the people of the farm, their own children, and maids and farmhands to read and reproduce the doctrines of Luther´s Small Catechism, tested by the priest at the annual catechetical meeting. The Church and the School, through this system, had several centuries of shared history. Catechism was, for a long time, the dominant teaching- and reading-book.

Fig. 1. Mose striking water from the rock. Härkeberga church, 1490´s.

In Germany and France, ideas on reading didactics were developed during the mid-nineteenth century. A method based on ”image-read-write” was developed, called Åskådningsundervisning from the German word Anschauungsunterricht and was applied in many different forms.

Teaching method could, for example, mean that students practiced the ”drawing” of a written word before learning the individual letters. In other applications, students could be trained to recognize the differences between the drawn, the written, what was read, and the real object. In Sweden, students practiced oral description by retelling what was illustrated on an educational poster. These ideas are reminiscent of teaching and communication techniques practiced by the Church for centuries.

Figure 2. Moses striking water from the rock, school illustration, ca 1880.

Today, Sweden has 1296 churches of medieval origin, the majority with more or less well-preserved paintings on the walls and vaulted ceilings. That these paintings had a teaching and influencing function is almost inevitable.

The paintings reflect, in many cases, events from the Bible, and for five hundred years, the individual and biblical events were connected to these images. The paintings´ depictions have included a tradition that Moses had horns, probably caused by an erroneous interpretation of the Hebrew text. The concept of Moses with horns was well-established in medieval church painting, and the idea was also transferred to early Swedish school illustrations from the late nineteenth century.

Today medieval church paintings are visible all the time to a large extent due to the light from large church windows and modern electric lighting. This has not always been the case, as most windows have been enlarged during the period 1750 to 1850. The change to larger windows is difficult to detect at first sight for today´s visitor. The change is revealed in that the painted figures are punctuated by window contours or portals, and the image context is, in many cases, damaged or mutilated.

Figure 3. Österunda church from the north-west. The window-less north wall, drawing by Olof Grau, 1754.

The Church and the School were pioneers when it came to teaching aids, for it was in this situation and in this environment that the need for media arose. Various visualization techniques in today´s teaching have their origins in both the Swedish Church and the Swedish elementary school. Priests and teachers were pioneers in using the latest technology in their education. The aforementioned Åskådningsundervisning is an example; sciopticons, filmstrips, film, and school TV were further aids tested early in their teaching during the twentieth century.

With the development in electronics, we now have simple screens and recording equipment making it possible, in a simple process, to retrieve text, images, film, and sound for an assembled group. However, where the medieval educational chamber surrounded the visitor and invited them to become a part of the presented show, several of today´s media risk being cramped in the lecture-theatre and being stereotyped when regarding the subject from the outside.

Both Church and School perhaps lost much of the live elements in their predecessors’ pedagogy. The teaching method reveals much about the attitude to knowledge and humanity that underlie their teachings.

The Shadow of a Window: Three different lighting applications

My first experience of active work in a medieval church was during the late 1970´s when I served as parish priest in Häverö church in Uppsala diocese. Almost immediately, I began to think about the medieval paintings and the myriad of characters found in the church, both on the walls and the vaulted ceiling. My curiosity increased over the years as to how this imagery was originally intended to function. When I began to study the lighting conditions for which the pictures were originally painted, their function became increasingly incomprehensible to me. With modern electric lighting and large windows, it is currently still difficult to discern many of the figures. What was the reasoning when the images were created?

Figure 4. Roslags-Bro church, south wall windows. The lighter area around the left window is a trace of a 15th century window having 2/3 of the present window´s height and placed a little to the left.

I have been able to distinguish three different lighting arrangements in church space in the time interval 1150-1850. A picture of Roslags-Bro church in Uppsala diocese made me aware of the fact that the early medieval churches probably only had a few narrow, but relatively high, openings for daylight. Traces of two different window designs are visible on the south wall in the masonry. The first consisting of the three high and narrow, now blocked, natural light inlets. The second is visible through fragments and contours of two arches of a size that are smaller than the present windows from the nineteenth century.

Most of the medieval church spaces in Sweden during the period between 1750 and 1850 have had new windows cut into the previously windowless northern wall of the building; on the south side, the medieval windows were enlarged and supplemented. At the same time, windows in the chancel east wall in several churches have been completely or partially bricked up. My discoveries are only possible to see ”in situ” and are not described in any documentation of the churches I have studied. The Swedish National Heritage Board has detailed descriptions of medieval churches, often together with information about the year of the latest window enlargement, but detailed information about those window periods I have discovered is mainly lacking.

Roslags-Bro church is the first example I have found to clearly illustrate, without a doubt, the three different window periods. The three earlier, very narrow windows are not only bricked up, they are also plastered over on the inside and covered with murals, painted during the fifteenth century, one of which is behind a brick pillar forming the framework for the cross-vaults.

Figure 5. Roslags-Bro church. Drawing by J. H. Rhezelius, 1635.

The later medieval windows can be discerned from the damaged and incomplete frescoes of the last window enlargement of the 1850´s. Window contours from the fifteenth century can be construed from the lintel, visible after these windows were also partly bricked up in connection with the third period.

Figure 6. Österunda church south wall, the sunlight angle shows a window from the period before the cross-vault was built.

In my second example, Österunda church also in Uppsala diocese, it is not possible to construe the window sizes in the same way as in Roslags-Bro, but the building illustrates broadly the same pattern of changes as in the Roslags-Bro. Österunda church was built in the late thirteenth century, and the church ceiling had initially high, wooden barrel-vaults. During the fifteenth century, these wooden vaults were replaced with star-formed brick vaults. In the attic, traces of the older, inner roof-structure can be seen together with traces of painting carried out earlier than the later stellar vaults.

On the south wall, contours of a high and remarkably narrow window are discerned through the plaster. During the 1750´s, the windows of the south wall were enlarged and the previously windowless north side was fitted with two large windows. Major repair work done in 1781 lowered the outer roof by giving the gable a flatter angle.

Figure 7. Close-up of the angled sunlight on the south wall with a trace of an earlier window.

The Österunda church has three different ”lighting applications.” The first has narrow and high, natural light adapted for a painting hidden today behind the brick walls of the star vaults.The second illumination from the light openings is tailored to illustrate the late fifteenth century vault- and wall-paintings, and the third illumination is seen with the two large windows carved into the north wall, together with the enlarged windows on the south wall.

This increased illumination can, as mentioned earlier, be seen as a result of the growing use of printed books, primarily hymnal, but also the catechism and the prayer books for general use, which required light.

Pedagogy of Light: A medieval interactivity

Despite the visible interference in church space being relatively easy to discover, one of the greatest changes is hardly visible. The lighting is the most crucial prerequisite for the function of painting and its narrative. Much of the contrast and narrative function, whereby the variable daylight would highlight specific images at specific times, disappeared with the larger windows. Scales of grey and the play of shadows are also effects of the sparse lighting, being easily underestimated or completely forgotten.

My aim has not been to trace the detailed differences in the painting technique, but to obtain an overall view of how the painted pictures may have functioned and been used to convey a story and a world view.

The change in the illumination of the church space paintings is of far greater importance than the small additions of image models appearing in Biblia Pauperum, Speculum Humanae Salvationis, and various master painters´ somewhat varied pictograms and choice of subjects.

My simulation of lighting conditions in Roslags-Bro church, starting with the traces of earlier windows, by reducing the current windows with masking paper, suggests that the images had a multiple function.

My observations suggest a planned lighting, using sunlight to highlight special images at specific times. Seasonal lighting conditions induced a moving play of pictures, functioning as a naturally linked worldview, in which the participants find themselves, not in a synthetically arranged education, which deviates from the world existing outside. On the contrary, the light-attenuated room clarifies the bright day outside. The two ”rooms” inside and outside do not contradict each other, for both are dependent on the same source of light.

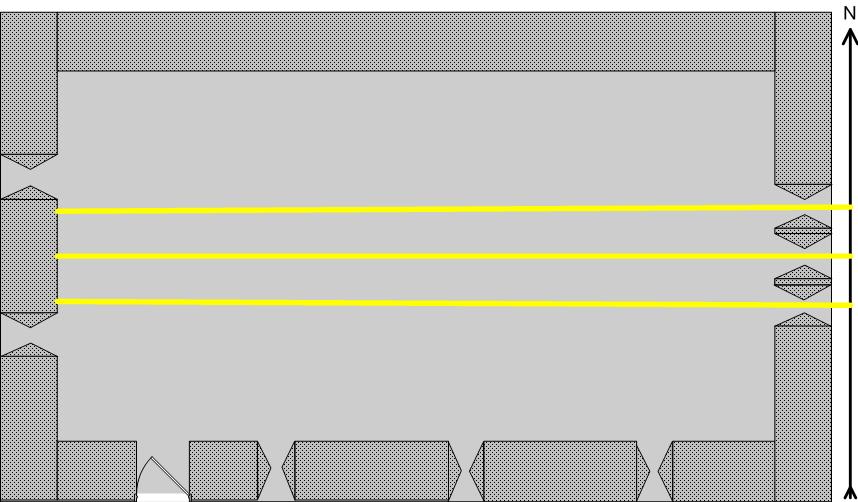

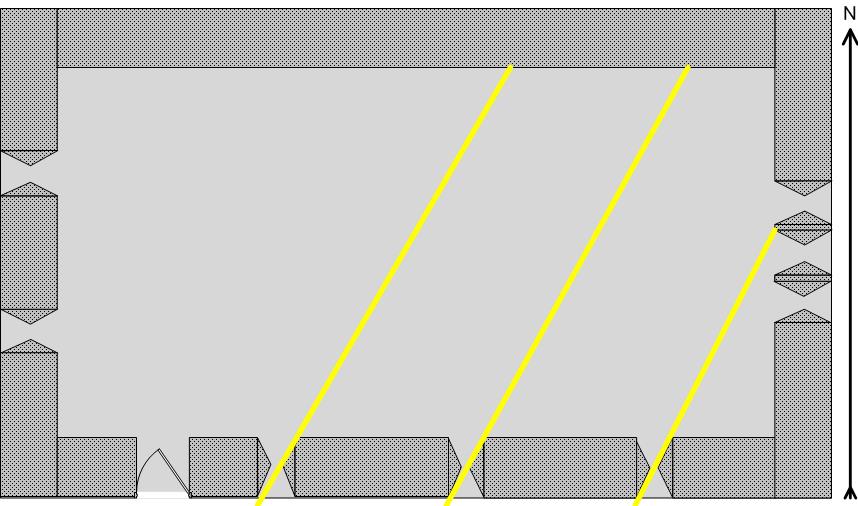

Figure 8. Reconstruction of the mid-13th century and incoming sunlight 6. am.

In the picture material studied in this research, motif and traditions from many different sources merged. The material is fragile, sometimes fragmented but, in the main, recognizable in the tradition of Christian teaching.

If the painted images functioned as an aid in teaching and preaching, they have most likely been using the natural play of light. My experiments with wax-candles made no noticeable difference in the general lighting in the main church space. If wax-candles or oil lamps were used, they probably had a limited effect, not altering the general lighting in the room. An attempt to read every holy day, during the church year, illustrated in a play of light would be to interpret a fragmentary study material too hard. However, it is reasonable to see illumination as a way to highlight general themes, for example, when the sun on December 19th at twelve o´clock, broke through and brightly illuminated the paintings of The Annunciation and Christmas Gospel, merging the two images with the picture above of Abraham, about to sacrifice his son Isaac on an altar.

Figure 9. Reconstruction of the mid-13th century and incoming sunlight 3. pm.

The entire painted program would seem almost impossible, if it originally was to function solely as illustrated material for a sermon. Neither before nor after the construction of more and larger windows were there increased opportunities for this form of teaching, rather the contrary. The medieval pedagogy deserves a better rating than being regarded as mere illustrations of a text or sermon. The light simulation suggests a very conscious pedagogy, designed to bring to life the central events in the images on the walls and the lower parts of the vaults, while it allowed the vaults´ other motifs to function as a representation of participants outside of time. A reading tradition is also suggested in cases where light joined together various motifs, where the motifs from the Old Testament were read as parallels with the Gospel accounts.

The impression presented by the image is a central feature that can be enhanced with daylight controlled lighting: an interpretation of reality where the viewer could perceive themselves as being encompassed. A pedagogy designed to be seen and shared in the activity between those who carried out the common course of events, and a way to transfer participants to another dimension.

In modern parlance, this is often called an interactive feature, or as in this case, education. With this approach, creative medieval technique shows striking similarities to modern, visualized computer-organized education.

Summary video. There is no audio

References

Grau, Olof, Beskrifning öfver Vestmanland, dess städer härader och socknar, A.F. Bergs boktryckeri, Vesterås, 1904

Jonsson, O. G., Skolplanschen: argument i spänning mellan bild och text, perspektiv och kontext, STEP, Department of Education, Uppsala University, lic., Uppsala, 2006

Jonsson, O. G., Bilden och texten: en studie av ljusets och seendets pedagogik, Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis, diss., Uppsala universitet, Uppsala, 2010

Lundgren. U.P., ”Den moderna skolan formas”. I Lundgren, U.P., Lieberg, C. & Säljö, R. Lärande Skola Bildning. Natur och Kultur, Stockholm, 2010

Pettersson, R., Homage to Albertus Pictor–An Early Information Designer? In M.D. Avgerinou, R.E. Griffin & P. Search (Eds.) Critically Engaging the Digital Learner in Visual Words and Virtual Environments. Loretto 2010

Pettersson, R., Ord, bild och form–pionjärer med nya idéer. Institutet för Infologi, Tullinge 2011

Wilcke-Lindqvist I., Roslags-bro kyrka, Ärkestiftets stiftsråd, Strängnäs 1989