Return to Theme table of content

Return to VJIC table of content

|

Alexandra Guerman is a Sydney-based researcher and curator. Alexandra has a Master of Curating and Cultural Leadership University of NSW. |

Photography as Classification and

Creation of Indigenous ‘Other’.

© Alexandra Guerman

“In knowing we control and in controlling we know”

“In knowing we control and in controlling we know” Foucault’s critical theory power-knowledge has been instrumental in the construction of knowledge through classification and scientific study of humans, which was inextricably linked with colonialism and colonial dominance over the ‘other’.[i] The scientific method developed by Anthropological discipline known as Ethnography, enabled to study and classify people that were different to the Western form.[ii]

| Viewers should be aware that, in some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Communities, seeing images of deceased persons in photographs, may cause sadness or distress and in some cases, offend against strongly held cultural prohibitions. |

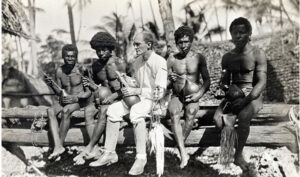

2.2 Photograph, Photographer unknown, Bronislaw Malinowski with Natives on Trobriand Islands

In the early twentieth century Polish-born Bronislaw Malinowski developed a way of explaining social structure of ‘others’ by systemic observation, claiming it can only achieve scientific value if it is “candid and above board.”[iii] However, the father of modern anthropology Malinowski did not separate himself from inherent European ethnocentrism as evidenced by his published diary, A Diary in the Strict Sense of the Term (Routledge 1967).[iv] Ethnographers thereafter faced the same shortcomings, as they failed neutralise their own connection to colonial powers, making their findings less than objective, and easier to feed back into the pre-existing assumption and stereotypes of the “Primitive Culture”, strengthening colonial agenda and justifying the expansion of colonial powers.

2.3 Alexandra Guerman,

Malinowski’s Controversial Diary Video, 2023

All of whom felt the urgency to document the “dying race” before its finite extinction. The general belief that the dying race was a natural process, was predominantly based on social Darwinism notion of “survival of the fittest.” Central to this, was the theory of evolution that regarded non-European races as infantile and at the beginning of their development along the lineal historic axis.[vii] They were at a starting point, whilst the Europeans waited patiently at the pinnacle of their intellectual, moral and physical development, having gone through their prehistoric and proto historic periods, and come out as superior race.[viii] These beliefs and attitude justified the techniques used to document and photograph the Indigenous peoples as scientific specimens.

“On the one hand, the reality of the photograph

is considered largely unproblematic, allowing

“transparent” access to subject-matter; on the

other, the language of the image is regarded

as conventional, highly constructed, its

understanding determined by Western culture.”[ix]

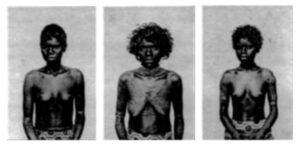

The photographers employed the Huxley and Lamprey methods in which the subject is photographed next to measuring devices demonstrating the subject’s anatomical measurements.[x] Subjects were photographed from all angles, their clothes stripped off, analysed, and prodded for scientific research. “The Aboriginal subjects had no advantage to gain through this scientific research and it only served to put them into a subservient relationship with the observers.”[xi] They were identified in generic terms of their age, race and gender, their personal information omitted from the caption. When identified, it was by allocated European names such as the photographs of a young Australian Aboriginal woman titled “Ellen.”[xii]

2.4 Photograph, Photographer unknown, Four views of a South Australian Aboriginal female ‘Ellen’ aged twenty-two, (c1870 according to Huxley’s photometric instructions’ (RAI 2116, 2117)

A major historical survey exhibition at the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW), Photograph and Australia 2015, presented key moments of photographic medium through history in Australia from colonial period to present.[xiii] It examines the way the photograph has been used to build and question national identity. The exhibition that was overwhelmingly about nineteenth century photography, radically displaced what has conventionally been seen until now. One theme that strongly ran through the show were the many images that complicated the standard picture of white/black relations. Among plethora of colonial photographers, it featured 22 works by Paul Foelsch.[xiv] These ranged from landscapes, modern developments of Darvin and portraits of Aboriginal people. The portraits of Aboriginal people share commonalities, “…women and men stare at the lens indignant or stoical.”[xv] It is important to note that the portraits of Aboriginal people are not available for viewing online, as the access to AGNSW archive is restricted due to cultural sensitivity.

2.5 Alexandra Guerman, protocols and

restricted material of Indigenous materials.

“These last three women ‘take my eye’ with their belligerence, their determined individuality, their anger resonating from their portraits. They are pissed off and I like them for it, these young warrior women…The collective gaze of the young women register volumes in anger and fear-were they molested or raped-often standard procedural practice in dealing with ‘savages’-by the policeman/photographer?” [xvii]

2.6 A. (from left to right), Paul Foelsche, Portrait of a woman, Minnigie, Limilngan NT, aged 20 yeas, (1887) gelatin silver photograph 15.3×10.3 Collection of Art Gallery of New South Wales 2.6 B. Paul Foelsche, Portrait of a woman, Aligator River, Bunitj NT, aged 30 years, (1880s) gelatin silver photograph 15.3×10.3 Collection of Art Gallery of New South Wales 2.6 C. Paul Foelsche, Portrait of a woman, Minnigie of Mary River, Limilngan, NT,

aged 18 years, (1880s) gelatin silver photograph 15.3×10.3 Collection of Art Gallery

of New South Wales.

Foelsche (1831-1914), a German born South Australian policeman, photographer and a dentist had a reputation of a ‘veritable sleuthhound of the law’.[xviii] He was sent to Northern Territory or as it is sometimes referred to a “last frontier” to head the first permanent police station in 1870. Starting out as a photography enthusiast Foelsche soon became the leading photographer in the Northern Territory, taking and distributing thousands of photographs at his own expense. He was able to disseminate his photographs to prominent members of society in Australia and abroad spreading his belief in the potential of the northern colony.[xix] Revered by historians for his hard work ethic, strong character, and intellect, the authorities have named Darwin’s streets after him.[xx]

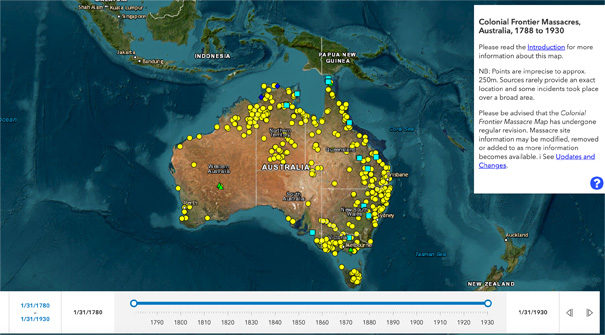

However, recently published findings indicate that contrary to long established views of Foelsche as a resilient pioneer,[xxi] today he would be considered a gun-nut for his obsession with firearms, and a ghoul for his fetish for Aboriginal ethnology.[xxii] As well as being a prolific photographer, Foelsche had penchant for collecting Indigenous human remains. A common practice of the times which saw items belonging to Aboriginal people, as well as human remains being sent to museums in exchange for a fee.[xxiii] The outback justice historian Tony Roberts wrote of Foelsche: “… the man who masterminded more massacres in the territory than anyone else was Inspector Foelsche. A former soldier he was cunning, devious and merciless with Aboriginals … Some considered him an expert on Aboriginals, not knowing that the skulls he studied were not merely collected by him.”[xxiv]

A final finding of the Colonial Frontier Massacres clearly indicated on the digital map that half the massacres of Aboriginal people on the Australian frontier were carried out by government forces, including police.[xxv]

2.7 A Digital map of Colonial Frontier Massacres. https://c21ch.newcastle.edu.a/colonialmassacres/ Caption: This website does not contain images or voices of deceased people. However, it does relate to violent past and current events that may be distressing to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. The aim of this project is to help build broader understanding among all Australians about the injustices that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have experienced in the past, their legacy today and the need for truth-telling as part of reconciliation. 1

Caption: This website does not contain images or voices of deceased people.

However, it does relate to violent past and current events that may be distressing to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. The aim of this project is to help build broader understanding among all Australians about the injustices that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have experienced in the past, their

legacy today and the need for truth-telling as part of reconciliation. 1

Brutalities committed by police forces were seen on all frontiers. However, Northern Territory police brutality stands out from the rest. [xxvi] Bill Wilson in his thesis on Police Force in Northern Territory and its systemic brutality against Aboriginal people wrote “Foelsche’s public pronouncements were measured, and he did not speak disparagingly of Indigenous people. In private, however, and in common with the majority of European settlers in the Territory, he disclosed his true feelings of imposing justice without mercy upon Aboriginal people to make his area of operations safe for Europeans.”[xxvii]

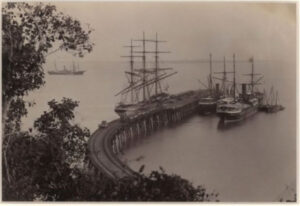

It is interesting to note the difference between the styles of Foelsche’s photographs when featuring different subjects. Below are two examples of photographs Foelsche took, that have a romantic aesthetic. The first one is of a Railway pier in 1888 and the second is a portrait of a young woman. Both have a beautiful composition, artistic framing technique and flattering lighting. In all aspects these works are pleasing to the eye, which is a complete contrast to a severe close-up portrait of the three Aboriginal women. It is clear these photographs were taken that he did not regard Aboriginal people as human, but rather a scientific object that needs to be studied and controlled.

2.8 Photograph, Paul Foelsche, Railway pier, 1888, AGNSW archive, 574.2014

2.9 Photograph, Paul Foelsche, Young woman with bicycle, 1880-1914 glass plate negative (dry plate)

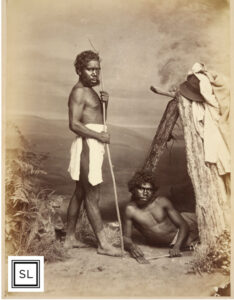

Another eminent photographer who enjoyed commercial success, in the second half of nineteenth’s century, was John William Lindt (1845-1926). Also, a German immigrant, he started out with taking mugshot format photographs, however soon moved to a more romantic and theatrical “tableau” form of photography. “These images are artistic rather than scientific and borrow their aesthetics from the German romanticism of Lindt’s training.”[xxviii] His most significant work is titled Australian Aboriginals, it is a series of tableaux photographs that were created in his studio in Grafton, on the Clarence River in NSW between 1873 -1874 captured a nostalgic notion of a dying race.[xxix]

2.10 J.W. Lindt, Australian Aboriginals portfolio, 1873-74, twelve albumen photographs, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

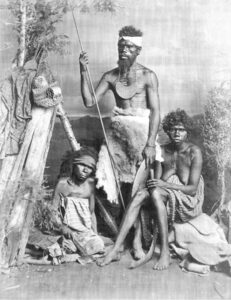

The photographs were taken using an elaborate set up, that replicated a bush setting, using painted backdrops and hunting and gathering objects, imitating untouched by Westerners, pre-contact Aboriginal way of life. “With their weapons laid aside and their wildness neutralised by the studio ambiance, they have been transformed into specimens – like the plants around them.”[xxx] The notion of untouched, which fascinated the Europeans can be further attributed to the nineteenth century idea of Indigenous cultures being static, and unable to modernise. Paradoxically though, Lindt had included in the composition of the photograph post-contact elements such as rifles, metal axes, bowler hats. The images often featured men wearing metal breast plates or gorgets. These were cheap brass plates inscribed with the person’s nick name, the station owner’s name as well as a mock title of a King. This was a pastoralist’s way of singling out the strongest and most influential member of the clan, and with his help, control the rest of the group.

“Sometimes the squatter appoints the best native near his station a ‘king’, and as a mark of this dignity he gives him a piece of brass containing his civilised name to wear on his breast. In return for food, tobacco, woollen blankets and similar things, the ‘king’ promises to watch his tribe, and keep them from doing damage to the white man’s property.”[xxxi]

Photograph, J.W. Lindt, Untitled, (Man with breast plate and spear, two women, one old and one young by bark shelter), albumen silver photograph, 1873-74. National Gallery of Australia, Canberra.

To today’s viewer these look staged and out of place, however at the time these were taken, Lindt was praised for their truthfulness. “The Clarence and Richmond Examiner reported on 8 December 1874 that Lindt’s photographs ‘represent very faithfully aboriginals, male and female of all ages, as the traveller finds them in the wild, and not as if just prepared for portraiture.’” [xxxii] Although Lindt’s photographs are not as dehumanising as Foelsche’s, it is important not to mistake their aesthetic quality for empathy. Lindt constructed the image of the “other” by not naming the individuals, allowing the Western imagination to construct a story for themselves. By leaving out vital details of his subjects, he made it impossible for future generations to identify then and obtain closure.

“Men, women and children stare back at me from

Lindt’s silent theatre,caught by the camera and

reduced to a state of perpetual anonymity.”[xxxiii]

2.12 Photograph, Two men, one standing, full length; one, half-length by a bark shelter, J.W. Lindt

Despite the fact that Lindt led many to believe that the subjects in his photographs were part of an authentic tribal existence, the reality was far from exotic. They were dislocated and banished to live on the outskirts of towns.[xxxiv] This did not stop him from national and international recognition, perpetuating the myth of the exotic “other” to farther frontiers. His portfolio “Bound in handsome cloth covers, and embossed with gilt lettering, was considered cheap at £2 2s, Lindt is reported to have ‘quitted nearly 100 copies and supplied his Excellency and most of the leading people of Sydney with a copy’, by mid-January 1875.”[xxxv]

In 2004 Sam and Janet Cullen and family[xxxvi] gifted a collection of thirty-seven albumen paper photographs by Lindt to the Grafton Regional Gallery, which they purchased at an auction in London. “They wanted to restore some dignity to the Aboriginal people in the photographs by identifying who they were as individuals rather than as archetypes.”[xxxvii] This changed the gallery’s direction and enabled the community to start an enormous recovery task of the anonymous subjects.[xxxviii] There are still so many more photographs that have not been identified and most likely never will, as the Australian Aboriginals portfolio is now not only in the Australian National Museum but also in the international collections of Musee de I’Homme (Paris), and the Peabody Museum. [xxxix]

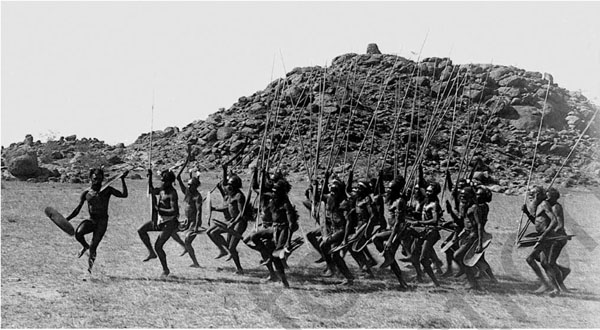

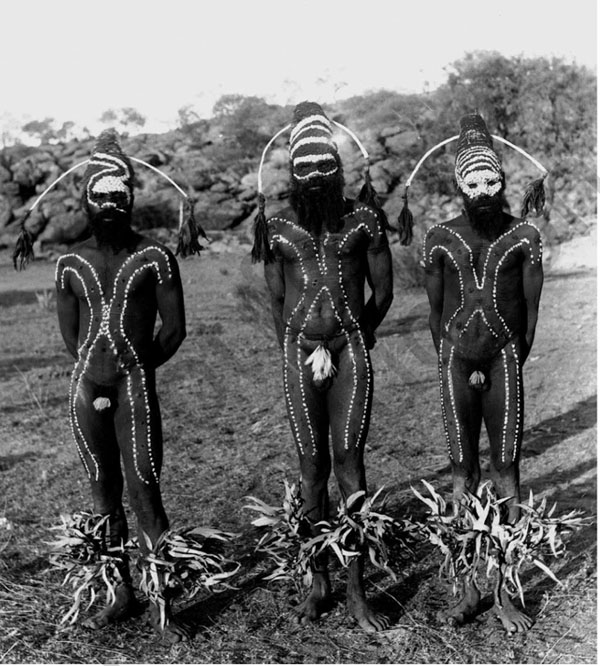

Another large and one of most influential collections of ethnographic material was amassed by Frances James Gillen and Walter Baldwin Spencer. The two met when Spencer travelled to Central Australia on a Horn Scientific Exploring Exhibition.[xl] He was stationed as a Biology Professor in Melbourne University at the time, while Gillen worked in Alice Springs Post as a Telegraph Station Master and lived in Central Australia for almost 20 years.[xli] Gillen had already undertaken some anthropological work with Arrernte including working on a vocabulary.[xlii] The two have agreed to collaborate on anthropological research, and in the period between 1896 and 1897 have carried out one of the longest and continues anthropological fieldworks in Australia in the nineteenth century.[xliii] This work provides a valuable archive for the descendants with whom Spencer and Gillen worked in Central Australia; the Arrernte, Anmatyerr, Kaytetye, Warumungu, Luritja and Arabana people who still have a substantial presence in the region.[xliv]

The objects that were collected during the research are dispersed all over the world and housed in cultural institutions in Australian and abroad. Whilst also having worked with numerous interpreters and guides, Spencer and Gillen relied on photography when verbal communication had limitations, specifically when it came to recording complex performance such as ceremonies.[xlv] “It was believed that the ‘mechanical eye’ was able to produce an accurate and objective replica, facilitating systematic organization and analysis, in the service of scientific enquiry.”[xlvi] But even with photographic evidence that presumably eliminates any contestation of subjective findings, Gillen and Spencer denied important aspects of Arrernte (Central Australia) cultural life and religion through their description of events.

2.13 Photograph, Spencer and Gillen, Arrernte welcoming dance, 1901, Courtesy of Museum of Victoria (BS786)

Peterson in his reworked version of a paper prepared for A Century at the Centre: Spencer, Gillen and ‘The Native Tribes of Central Australia’ conference provided an example of how deeply rooted prejudices blinds one’s understanding of events. In the example of the image below when describing the ceremony, they wrote:

“At present time the natives of Central Australia carry on their ceremonies in secrecy…A word of warning must however be written in regard to this ‘elaborate ritual’…. It must be remembered that these ceremonies are performed by naked howling savages who have no idea of permanent abodes…” They conclude by stating “Apart from the simple but often decorative nature of the design on the bodies of the performers, or on the ground during the performance of the ceremonies, the later are crude to the extreme. It is difficult, if not impossible, to write an account of the ceremonies of these tribes without conveying the impression that they have reached a higher stage of culture than is actually the case.” [xlvii]

2.14 Photograph, Spencer and Gillen, Arrernte Erkita corroboree., Alice Springs, c. 1896. Courtesy of Museum of Victoria (BS786)

Reading their account of events, it is as though the two ethnographers could not reconcile within themselves what they witnessed against their pre-existing understanding of the ‘other’. Preferring to downplay the visual and staying true to the conformist notion of Western lineal teleology.[xlviii] Even though they did not load the images with hidden agenda by using props or dehumanise the subjects by stripping them off their dignity, they did not let the photographs speak for themselves either, choosing to control the narrative. To admit that the local people in the photographs appeared magical and powerful would be to humanise them, to relinquish control, to admit objectification and mistreatment of fellow men, which went against modernism itself.

“The context of the photograph is everything and

the “truth” of the medium is dependent almost entirely

on understanding of how it’s being used”.[xlix]

Over the last two centuries the image of the ‘other’ has been engrained into the psyche of Aboriginal people leaving them to fight the disproportionate battle for self-representation.[l] The last several decades has seen a shift towards decolonial movements, in attempt to disrupt colonial and settler-colonial logic. As part of this movement, active repatriation process has swept through cultural institution all over the globe, in the hope to provide closure to the communities that experienced loss and oppression.[li] Another aspect of decolonisation is new mode of self-representation and identity-formation to counter previously manufactured damaging stereotypes. The numerous deceptive representations of Aboriginal people have served as a wealth of inspiration for contemporary photographers and media artist, which continue to inspire and motivate strong political, humorous and powerful re-representations.[lii] By choosing to work with photography the artists reclaim the medium that was responsible for misinformation and control over Aboriginal people since the nineteenth century. “These artists have taken up arms (cameras) and have commenced the struggle of repossession of self-image.”[liii]

2.15 Alexandra Guerman, Introduction to the next thread.

[i] In critical theory, power-knowledge is a term introduced by the French philosopher Michel Foucault (French: le savoir-pouvoir). According to Foucault’s understanding, power is based on knowledge and makes use of knowledge; on the other hand, power reproduces knowledge by shaping it in accordance with its anonymous intentions.[1] Power (re-) creates its own fields of exercise through knowledge.

The relationship between power and knowledge has been always a central theme in the social sciences

[ii] B. Malinowski, Argonauts of the Western World, 2014, Routledge

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] M.W. Yung, Writing his Life through the Other, The Anthropology of Malinowski, The Public Domain Review, 2014, https://publicdomainreview.org/essay/writing-his-life-through-the-other-the-anthropology-of-malinowski

[v] E. Fernandez, Collaboration, demystification, Rea-historiography: the reclamation of the black body by contemporary indigenous female photo-media artists, 2002, Edith Cowan University

[vi] Ibid.

[vii]S. Spear, Teach NYPL: The Role of Social Darwinism in European Imperialism, 2015, https://wayback.archive-it.org/18689/20220313040506/https://www.nypl.org/blog/2013/10/15/classroom-connections-social-darwinism-european-imperialism

[viii] J.R. Ryan, Picturing the Empire, Photography and the Visualization of the British Empire, Chicago Press, 1998

[ix] T. Wright, “Photography: Theories of Realism and Convention”, from Anthropology & Photography 1860-1920, edited by Elizabeth Edwards, New Haven and London, Yale University Press, 1992, p. 18.

[x] Henry Huxley devised the method of photographing subjects naked in certain viewpoints as front on and in profile, next to rulers. The photographs were undertaken in the anthropological practice of anthropometry which compares the physiognomy of different ethnic groups and measures them against European physiognomy.

[xi] E. Fernandez, 2002.

[xii] L. Butler, Imaging and Imagining the Pacific, A journey through myth, beauty and reality, 2010, https://www.canterbury.ac.nz/library/search-our-collections/special-collections/exhibitions-and-featured-collections/imaging-and-imagining-the-pacific/Imaging-and-Imaging-the-Pacific.pdf

[xiii] A. Frost, ‘The Photograph and Australian review – a superb study of national identity’, The Guardian, 2015

[xiv] Photograph and Australia, 2015, Art Gallery of NSW, https://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/artsets/51b88k

[xv] E. Fernandez, 2002.

[xvi] Ibid.

[xvii] B. Croft, Laying Ghosts to Rest, 2002, Routledge in E. Fernandez, Collaboration, demystification, Rea-historiography: the reclamation of the black body by contemporary indigenous female photo-media artists, 2002, Edith Cowan University

[xviii] R. J. Noye, ‘Foelsche, Paul Heinrich Matthias (1831–1914)’ Australian Dictionary of Biography, 2006, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/foelsche-paul-heinrich-matthias-3543

[xix] Ibid.

[xx] P. Daley, Police interactions with Aboriginal people are scarred by Australia’s violent frontier history, The Guardian, 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/postcolonial-blog/2022/mar/19/police-interactions-with-aboriginal-people-are-scarred-by-australias-violent-frontier-history

[xxi] P. Daley, Police interactions with Aboriginal people are scarred by Australia’s violent frontier history, The Guardian, 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/postcolonial-blog/2022/mar/19/police-interactions-with-aboriginal-people-are-scarred-by-australias-violent-frontier-history

[xxii] Ibid.

[xxiii] Indigenous Repatriation, https://www.arts.gov.au/what-we-do/cultural-heritage/indigenous-repatriation

[xxiv] P. Daley, 2022

[xxv] Colonial Frontier Massacres in Australia, 1788-1930, University of New Castle, https://c21ch.newcastle.edu.au/colonialmassacres/

[xxvi] P. Daley, 2022

[xxvii] W.R. Wilson, A Force Apart, A History of the Northern Territory Police Force 1870 – 1926, Northern Territory University, 2002

[xxviii] Ibid.

[xxix] K. Orchard, J. W. Lindt’s Australian Aboriginals (1873–74), History of Photography, Routledge, 2015

[xxx] R. Poignant, (1992). Surveying the field of view: The making of the RAI photographic collection. In E. Edwards (Ed.), Anthropology and photography, (pp. 42 – 73) New Haven and London: Yale University Press

[xxxi] C. Lumholtz, Among Cannibals: an Account of Four Years’ Travels in Australia, and of Camp Life with the Aborigines of Queensland, John Murray, London, 1889, pp 362–63. In ‘Kings and the expansion of the pastoral frontier’, National Museum of Australia. https://www.nma.gov.au/explore/features/aboriginal-breastplates/pastoral-expansion

[xxxii] N. Teffer, 2014

[xxxiii] K. Orchard, ‘J. W. Lindt’s Australian Aboriginals (1873-74)’, History of Photography, Routledge, 2015

[xxxiv] E. Farrow-Smith & C. Marciniak, Mystery of the historic Lindt photographs solved by family of main subject, 2015, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-04-17/mystery-of-the-lindt-photographs-mystery-solved/6402254

[xxxv] K. Orchard, 2015

[xxxvi] Samuel (Sam) Cullen was a pre-eminent Sydney businessman, vice-chairman of Sotheby’s Australia from 2010 to 2016, art collector and philanthropist. https://www.smh.com.au/national/sceggs-saviour-art-collector-and-philanthropist-20201207-p56l7l.html

[xxxvii] The light of day: J W Lindt photographs at RAHS, https://www.sydneybarani.com.au/jw-lindt-photographs-at-rahs/

[xxxviii] E. Farrow-Smith & C. Marciniak, Mystery of the historic Lindt photographs solved by family of main subject, ABC News, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-04-17/mystery-of-the-lindt-photographs-mystery-solved/6402254

[xxxix] K. Orchard, 2015

[xl] A. Petch, ‘Spencer and Gillen’s Work in Australia: The Interpretation of Power and Collecting in the Past’, Journal of Museum Ethnography, No. 15, Papers Originating from MEG Conference 2002: Power and Collecting, National Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh (March 2003), pp. 82-93 (12 pages) Published By: Museum Ethnographers Group

[xli] Ibid.

[xlii] Ibid.

[xliii] Ibid.

[xliv] Spencer and Gillen, A Journey through Aboriginal Australia http://spencerandgillen.net/spencerandgillen

[xlv] N. Patterson, Visual knowledge: Spencer and Gillen’s use of photography in the native tribes of Central Australia, Australian Aboriginal Studies, 2006, Australian National University, pp12-22

[xlvi] E. Fernandez, 2002

[xlvii] N. Patterson, 2006

[xlviii] Ibid., Where the Arrernte Indigenous people were at the origins, “humans in the ‘chrysalis phase’ of social evolution, not the advanced sophisticates documented in the images”

[xlix] A. Frost, 2015

[l] E. Fernandez, 2002.

[li] S. Collard, Spears stolen by Captain Cook from Kamay/Botany Bay in 1770 to be returned to traditional owners, The Guardian, 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2023/mar/02/spears-stolen-by-captain-cook-from-kamaybotany-bay-in-1770-to-be-returned-to-traditional-owners

[lii] E. Fernandez, 2002.

[liii] ibid.