Return to theme table of content

Return to VJIC table of content

Thread # 6

Jewish Photographic Perspectives, Part 3

Henryk Ross: The Łódź Ghetto Photographs

© Robert Hirsch 2022

www.lightresearch.net

VASA Journal on Images and Culture (VJIC),

Theme Editor and Writer

Those are my principles and if you don’t like them …

well, I have others.

Groucho Marks

This second of two essays continues to explore the photographic activities of Henryk Ross (1910-1991) who documented living inside the Łódź Ghetto (pronounced “Lawch”) from 1940 to 1944. Officially, Ross worked for the Statistics Department of the ghetto’s Jewish Administration, photographing the ghetto’s Jewish inhabitants for identification cards and for use in Nazi propaganda. When Ross was not engaged in his bureaucratic capacity, he risked his unique privileges and his life to photograph the reality of daily ghetto existence. Ross understood the importance of photographically documenting the Nazi’s genocide to repudiate those who would not believe or who would deny the Shoah. Ross’s photographs lay bare the issues regarding leadership, social class, forced labor, starvation, and the obliteration of religious institutions in a controlled environment where death was the destination.

Notes: Additional information about some of the images can be found at the end of this essay. Images have been minimally adjusted to facilitate online viewing, but have not been overtly edited from their source. There has been confusion regarding who has made many of the Łódź Ghetto photographs. A number of Ross’s photographs have been attributed to Mendel Grossman although the negatives are in the Ross archive. I believe that possession of negatives is generally the best method of attribution even though some of Ross’s images survive without the negatives, which is not surprising given the history that follows. Also, bear in mind that Grossman’s images were published posthumously without his input. Regardless of the maker, what is essential is their existence as visual proof of the German extermination of the Łódź Ghetto Jews.

Through the eyes of a few we can see many.

A Paradox Revealed in Images:

Tenuous Privilege and Covert Resistance

6.1 Henryk Ross. Łódź ghetto policemen posing for Ross’s camera, 1941—1942. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada.

Ross’s photographs are a study in opposites, for they give the illusion that ghetto conditions were not so terrible, seemingly making the body of his effort disturbing. However, they are unrepresentative and stand in stark contrast to the reality of the majority of the ghetto inmates. They depict a tiny minority of the ghetto prisoners—the more privileged Judenrats and their children who lived under better conditions. It is unclear why Ross took these pictures or the relationship he had with the people depicted. Was he compensated to take pictures? Was he part of the elite? Or did he want to commemorate these commonplace social interactions as a rebuke against the horror? Such intimate photographs, having the façade of classic family snapshots, have led some to question whether Ross exaggerated the danger he faced from the Jewish police, whom he portrayed both as affable, community protectors, and those who got extra rations. Did Ross want to distance himself from the Jewish Council and make himself appear part of the underground struggle or are we seeing the intricacy of the human survival instinct? Furthermore, many of Ross’s depictions of Chaim Rumkowski (Head of Judenrat,) contradict the way most Holocaust centers have presented him—as an archetypal, autocratic traitor.

6.2 Henryk Ross. Łódź ghetto police men receiving extra rations, 1941—1944. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada.

6.3 Henryk Ross. Aged and sick Łódź ghetto residents being deportation, circa 1942. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada.

6.4 Henryk Ross. People trying to escape out of a hospital window as Jewish ghetto police round them up for deportation, circa 1942. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada.

6.5 Henryk Ross. Łódź ghetto Jewish police escorting residents for deportation, circa 1942—1944. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada.

6.6 Henryk Ross. Łódź ghetto Jewish police (wearing Star of David arm bands) loading fellow residents into a boxcar bound for death camp, circa 1942–-1944. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA.

6.7 Henryk Ross. Food pails and dishes left by deported Łódź ghetto prisoners bound for a death camp, 1944. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada.

On the other hand, Ross photographed bewildering ghetto scenes such as a childhood version of “cops and robbers,” which was modified to “Nazis and Jews” or “ghetto policemen and Jews.” Here, children dressed up as SS-men or ghetto policemen and rounded up their playmates for deportation. Some find this confounding. However, in retrospect, it can be noted that games assist children in learning about their environments. In that sense, this “Bizarro World” game, where everything is reversed, may have helped the children cope with the veracity of their ghetto existence. This picture raises many questions: Why did the Ross record this scene? What were the boys thinking when playing this game? Where did they get the uniform? What did adults think when seeing the children play? Is this different from post-World War II American children playing cowboys and Indians?[i]

6.8 Henryk Ross. Playing as Ghetto Policeman, 1943. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada.

Such seemingly perplexing images were not made public until 1997 – six years after Ross’s death – when his son made his collection accessible. Such imagery explains why Ross’s archive was harshly judged for many years and why Holocaust institutions were not interested in his collection, with its alternative renditions of ghetto culture and leadership. His son recalled:

He tried to get his pictures published in the 1950s, but no one wanted to know. The iconic pictures of the Holocaust were of atrocities, horrors. The message of these pictures is not so straightforward.[ii]

6.9 Henryk Ross. Ghetto Elite Dancing, 1943. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada.

Towards the end of his life, Ross revisited his ghetto photographs. He made a scrapbook of contact sheet prints that he arranged in rows, not in sequence, structuring the images out of their original time and place. At first this seems to be a puzzling way to edit.

6.10 Henryk Ross. Łódź Ghetto Folio, page 1, 1940—1945; assembled 1962—1987. 11 x 8 9/16 inches. Gelatin silver prints. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada.

However, Ross’s timeline is actually more like real life: complicated, not a straight story, people and places weave in and out and go backward and forward in time. Ross’s arrangement is an accurate representation of the chaotic way he had to make these photographs. His distinctive approach takes into account the random and unexpected, including the water damage his buried negatives suffered, which altered how he later came to view his original intentions. Once again this demonstrates how photographs do not necessarily follow a coherent path and are often idiosyncratic and subject to change over time. We also see how memory, especially of traumatic events, can play an enormous role in how we recall and understand the events that shape our lives. This allows everyday stories, within the larger story, to take on a significance that was buried beneath the surface, just like Ross’s impaired negatives.

The Eichmann Trial: Time Shifts Understanding

Ross’s artless photographs, often made without looking through a viewfinder, or while peering through cracks, imbues them with a sense of resolve, acting as reminders of the long ugly history of antisemitism that dates back to ancient Greece. They portray the breadth and depth of Jewish ghetto life through the eyes of a professional Jewish photographer. Made under the terrifying circumstances, his visual authentication stands in defiance of the Nazis’ goal of annihilating the Jewish people, culture, and history that is foundational to western and Mideastern civilizations.

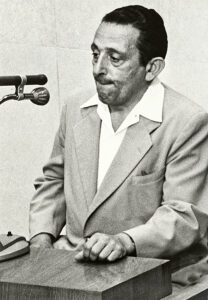

An exorcism of passing time was necessary before the value of Ross’s contradictory imagery became apparent. Then, like smoldering ashes, they came roaring back. This arising led to Ross’s harrowing testimony and his photographs being used as evidence in the 1961 Jerusalem trial of SS officer Adolf Eichmann, the implementer of the Final Solution.[iii] It was the first time in 2,000 years that the Jewish people sat in judgment of someone who had tried to destroy them. Jews did not have plead for justice to be done, which usually fell upon deaf ears. Instead, they got to sit in judgment. It also lifted the toxic, shadowy veil of concealment, silence, and shame surrounding the trauma of the survivors and their decedents. After the war, in his testimony at the Eichmann trial, Henryk Ross described the circumstances under which he took the photographs.

6.11 Unknown photographer. Henryk Ross testifying in the trial of Adolf Eichmann at the Jerusalem District Court, May 2, 1961. Ghetto Fighters’ House Archives (Itzhak Katzenelson Holocaust and Jewish Resistance Heritage Museum, Documentation and Study Center), Western Galilee, Israel is the world’s first museum commemorating the Holocaust and Jewish heroism.

On one occasion, when people with whom I was acquainted worked at the railway station of Radegast, which was outside the ghetto but linked to it, and where trains destined for Auschwitz were standing – on one occasion I managed to get into the railway station in the guise of a cleaner. My friends shut me into a cement storeroom. I was there from six in the morning until seven in the evening, until the Germans went away and the transport departed. I watched as the transport left. I heard shouts. I saw the beatings. I saw how they were shooting at them, how they were murdering them, those who refused. Through a hole in a board of the wall of the storeroom I took several pictures.[iv]

The Eichmann trial was a great awakening for numerous people — including many Israelis and this writer — who learned the details of the Holocaust for the first time. The trial gave the world the names, faces, and histories of the Holocaust’s victims, asserting their human dimension. After the trial more survivors decided they did not want to be mere creatures who were acted upon. Instead, they took up personal agency and began telling their stories. It also marked the expansion of investigative Holocaust scholarship, which in turn broadened how Ross’s photographs were appraised. Finally, it showed the importance of the existence of the state of Israel. Before the re-establishment of Israel, Jews were in a constant state of Exodus and never felt truly welcome anywhere else. Had there been a Jewish state, it could have provided a refuge, reminding us that history is a mirror against which we view and define the present. With the benefit of reflection, Ross acted as a photo-journalist employing his photographs as witnesses, documenting what you would have seen had you been there and serving as a memory aide. General Eisenhower was so shocked when he saw a liberated concentration camp that he ordered photographs and films to be made to verify the nauseating horrors, thinking people would not otherwise believe it. Unfortunately, with the rise of Holocaust denial, disinformation, and inversion, Eisenhower was right. As Ross later stated:

Just before the closure of the ghetto (1944) I buried my negatives in the ground in order that there should be some record of our tragedy, namely the total elimination of the Jews from Łódź by the Nazi executioners. I was anticipating the total destruction of Polish Jewry. I wanted to leave a historical record of our martyrdom.[v]

6.12 12th April 1945: In the centre with hands on his hips, General Dwight D Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander looks at the piles of bodies belonging to Russian and Polish prisoners shot by the Germans in a camp at Ohrdruf, Germany. (Photo by Keystone/Getty Images)

The conditions under which Ross made his pictures are unnerving because they call into focus the side of human nature many do not want to acknowledge: that economic and social status in the ghetto was similar to pre-ghetto life. These circumstances were compounded by the burden of survivor guilt, which resulted in many people not wanting to talk about what happened, believing the finest people perished.

6.13 Henryk Ross. Man who saved the Torah from the ruins of the synagogue on Wolborska Street, 1939–-1940. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada.

At the conclusion of Night (1960), an autobiographical account of surviving the German death camps, Elie Wiesel wrote: “For in the end, it is all about memory, its sources and its magnitude, and, of course, its consequences,” Wiesel draws the conclusion that “the best of us died.”[vi] However, reality is less noble. Everyone in the sights of the sadistic Nazi death cult faced similar dilemmas and under such stress human solidarity can diminish. Ross himself was traumatized. Upon liberation he weighed only 84 pounds/38 kilograms and never really found solid footing after the Shoah.[vii]

Like a revolving door of goodness and horror, the duality of Ross’s disconcerting photographs juxtaposes beauty and hope in the mist of calamity and despair. Now we can consider them a form of social photographic vérité, which chronicled people in everyday situations under dire and nerve-racking conditions when they were trying to live with the uncertainty of certainty. Although Ross made his photographs in daylight, they are all about a culture vanishing from the light into pitch darkness. Like unfixed photographic prints, they disappear, yet make a case against the fatalism that attempted to erase Jewish culture from the collective memory. Rather than succumbing to despair in a desperate situation beyond his control, Ross practiced courageous resistance in the face of deadly, overwhelming odds.

6.14 Henryk Ross. A young child smiling, 1940—1944. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada.

Either Or: A Matter of Choice

It is sanctimonious to think people lived or died solely based on their choices, when the entire structure of the Łódź environment was designed for one purpose: to cause death… In a situation that consumed so many lives, impossible decisions had to be made—there was no space for the luxury of heroism. All the inmates were faced with what American scholar and Holocaust analyst Lawrence Langer has called “choiceless choice.”[viii] Although Ross shared no responsibility for the situation, he made the fitting decision to survive while defying German orders. Ross’s work shows human agency in what would otherwise only be an abstract numerical horror story. This makes Ross an “Exception,” a nonconformist, a risk taker, whose actions can facilitate change. His archive is like an iceberg. Its cumulative power lays below the surface as an anthology of collective trauma. As the German philosopher Hannah Arendt insisted, moral choice exists, even under totalitarianism, and that choice has political consequences even when the chooser is politically powerless:

For the lesson of [resistance to the Holocaust] is simple and within everybody’s grasp. Politically speaking, it is that under conditions of terror most people will comply but some people will not, just as the lesson of the countries to which the Final Solution was proposed is that “it could happen” in most places but it did not happen everywhere. Humanly speaking, no more is required, and no more can reasonably be asked, for this planet to remain a place fit for human habitation.[ix]

Conclusion

Ultimately, the sheer number of Ross’s photographs offers the most diverse view of contemporaneous responses to the Shoah by depicting the human dance of forced collaboration and simultaneous active resistance. What we witness is how ghetto life gets reduced, reduced, and reduced until it finally disappears completely. Bearing witness to the collapse of German civilization is essential, making visible what is hard but necessary to see. Witnessing requires seeing another’s pain as no different from our own.[x] The kind of pain Ross recorded was as blinding as pointing his camera into the sun. These photographs, walking the tightrope between presence and absence, do not protect us from their grief or solve the contempt for life that produced them. This is precisely why one needs to learn to examine problems when you really want to look away. We may prefer to run away and weep, but the willingness to see opens one to the process of discovery, which is the prologue to action.

This is what makes Ross’s work compelling, for the stories his photographs tell are like life itself: they are often about circumstances we cannot comprehend. Stories are never neutral. Hence the role of a storyteller is to decide what to include and exclude; what to highlight and what to downplay. A good storyteller distills the complex situations into viable and significant segments that guide our understanding of cultural situations. In this sense, Ross is an alternative story-telling photographer who generated counter-images to those of the oppressor, which can be perceived from multiple perspectives.

First of all, Ross’s work affords an insiders point of view, thus providing the missing, active resistance portion to the classic Holocaust narrative based on German and Allied archives with their emphasis on passive enslavement and liberation of the European Jews. The second is how the asymmetry of time invites chance. Entropy tends to increase over time, in this case, it transformed some of the buried, water damaged negatives into supercharged psychological containers of lost time and place. Ross must have known that whatever would become of his efforts was unpredictable, yet he chose to tell his story in hope of making a difference in a future in which he might not exist. His body of work exemplifies why we need to take in other people’s traumatic stories. In a mythical sense there is a persuasive #MeToo element to Ross’s over-arching story, which shows how totalitarian regimes can destroy those without power and act unrepentant. In contrast, Ross expresses the range of ways that the vulnerable can defend themselves against tyranny and become unexpectedly strong in the end. Finally, every verbal and written description of the Holocaust is deficient in some way of conveying the cruel depths of hardship, humiliation, and constant terror people experienced in Shoah, thus making images that can communicate to us on a different internal wavelength a valuable addition when attempting to comprehend the incomprehensible.

6.15 Henryk Ross. Two Girls, 1941—1944. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada.

Ross’s compendium exhibits how an imperfect person can accomplish remarkable things and that human behavior is rarely one thing or another, but rather a fusion of diverse and often contradictory actions. Ross’s photographs serve as a humanistic expression of rebellious disobedience. In total they are an affirmation of enduring love for those who he shared ghetto life with – proof that one’s own actions matter even when everything else appears lost. In the end, it is a stark reassessment that remembrance without concrete individualistic action does not honor the social responsibility aspect of the Jewish precept “tikkun olam” – trying to repair and heal a bloody and beautiful world.[xi] To conclude, ask yourself: What would you have done in Ross’s situation? The choices we make define who we are….

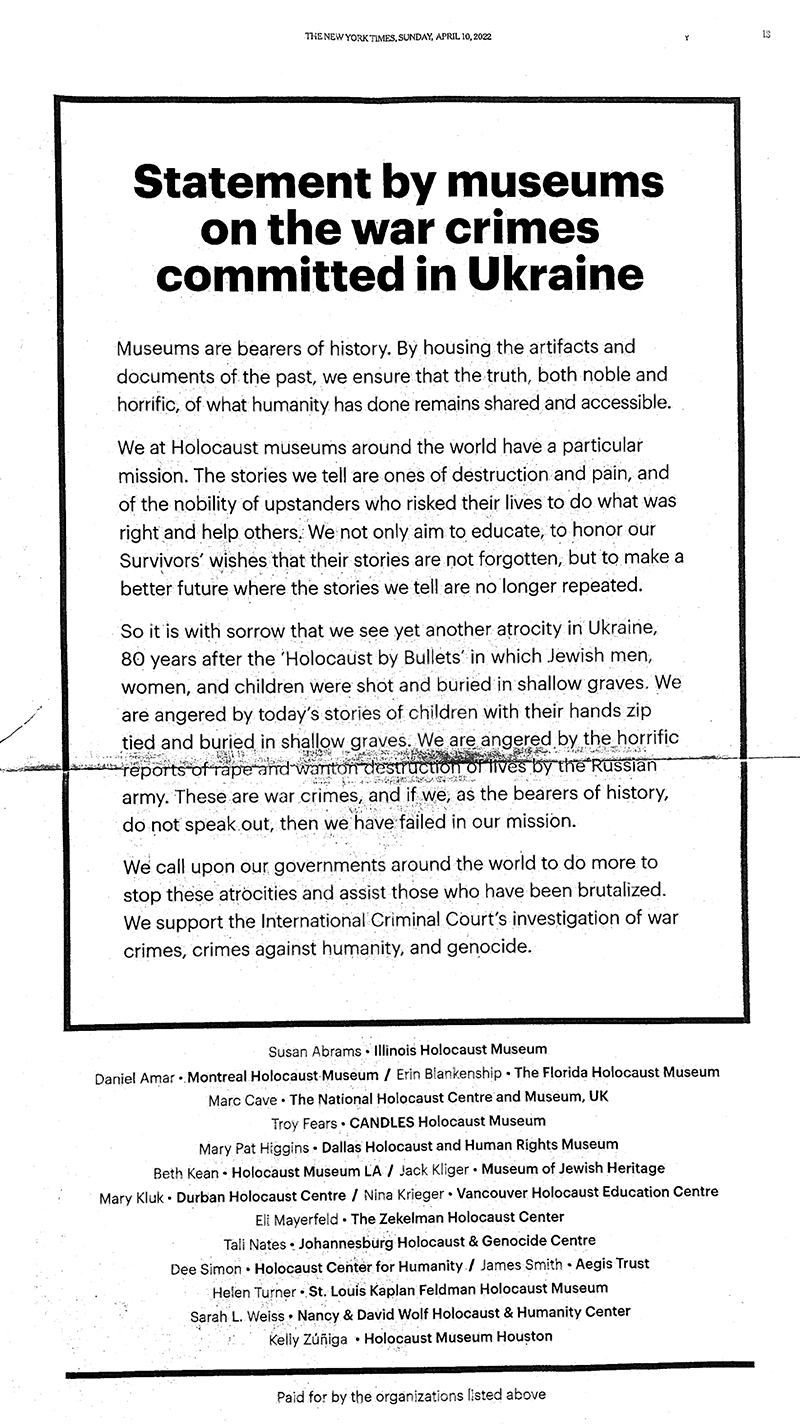

Afterword: Putin Invades the Ukraine & Lies Become Truth

“The past was erased, the erasure was forgotten,

the lie became the truth.”

George Orwell, 1984

During the Holocaust, an estimated 1.2 to 1.4 million Ukrainian Jews were slaughtered. Henryk Ross’s photographs demonstrate a central political lesson of the 1930s: democracies cannot win peace at the expense of the freedom of others, and the triumph of nefarious tormentors depends on whether their prey psychologically surrenders or resists. This point is self-evident, as in the course of writing this essay, Russia has aggressively invaded the Ukraine. Kleptocratic dictator Vladimir Putin is utilizing brutal, authoritarian playbook tactics that include: demonizing Others, civilian warfare, and suppression that include false flags, Double Speak, inversion of facts, and rewriting history to erase Ukraine’s statehood.[xii] By blanketing the public sphere with propaganda,[xiii] Putin makes people afraid to speak with one another. This sense of fear makes people feel isolated and much less likely to counterattack. Hannah Arendt referred to widespread loneliness as an underlying condition for totalitarianism. Punishing free dialogue allows Putin to make preposterous claims, such as using the pretext of “de-Nazification” for his aggression and forbidding people to declare his actions an act of war. Accusing the Ukrainians of being Nazis and drug addicts, Putin claimed his invasion was “to protect people who for eight years now have been facing humiliation and genocide perpetrated by the Kyiv regime” and that Russian society needed a “self-purification” from the pro-Western “scum and traitors” in its midst.

This is the same kind of Big Lie propagated about Israel by Palestinian terrorist leader Yasser Arafat after he made common cause with the Soviet Union to rewrite history, demonize the Jewish state, and subvert the West by twisting its collective mind and destroying its moral compass. China’s leader, Xi Jinping, wants to erase Hong Kong, Taiwan, and the Uyghurs, just as BDS founders have publicly stated that their goal is to erase Israel, a country that equals 1/100 of one percent of the world’s surface (Israel doesn’t even appear on maps in most Arab and Muslim countries).[xiv] The leader of the Palestinian Liberation Organization and the Palestinian Authority, Mahmoud Abbas, published his doctoral thesis The Other Side: The Secret Relationship Between Nazism and Zionism (1984) while attending Patrice Lumumba University in Moscow. Abbas outrageously claimed that Zionists were “fundamental partners” with the Nazis and equally responsible for the Holocaust in order to encourage Jews to emigrate to Palestine. Such anti-Zionism is a dog whistle for antisemitism that transposes Jews into racist Nazis who practice apartheid, use their space lasers to start wild fires, and deserve to be universally boycotted. This type of libel also occurs in the art world. A recent example is 15th Documenta (2022), which was curated by an Indonesian collective (Ruangrupa) whose members displayed antisemitic works and accused Israel of apartheid, resulting in resignation of the show’s managing director Sabine Schormann. Ruangrupa claimed that there were Jewish Israeli artists among the 1,500 participants, but did not identify them.[xv] Within this context, Ross’s photographs are a reminder of what has changed and what has remained the same and how much of the world continues to see Jews as not being like everyone else.[xvi]

Volodymyr Zelensky: Ukraine’s Jewish President

Putin’s bombs have fallen close to the site of Babyn Yar where the Nazis killed tens of thousands of Jews in one of the worst single massacres of the Holocaust. This was carried out with the active assistance of Ukrainians, who have a long, ugly history of antisemitism and who also made up a large number of concentration camp guards.[xvii] However, the Ukraine now has a Jewish president, Volodymyr Zelensky, who emotionally asked, “What is the point of saying ‘never again’ for 80 years if the world stays silent when a bomb drops on the same site of Babyn Yar?”

On March 2, 2022, in a Hebrew-language post to his Facebook page, President Zelensky urged Jewish people around the world to speak up, as he accused Russia of seeking to “erase” Ukrainians, their country, and their history: “I am now addressing all the Jews of the world. Don’t you see what is happening? That is why it is very important that millions of Jews around the world not remain silent right now. Nazism is born in silence. So shout about killings of civilians. Shout about the murders of Ukrainians.” Zelensky also referred to a Russian missile strike the day before that hit a television broadcast building near the Babyn Yar Holocaust memorial site, causing damage to the surrounding area. “We all were bombed last night in Kyiv, and we all died again at Babyn Yar from the missile attack, even though the world pledges ‘Never again,’” he wrote. “You are killing the victims of the Holocaust again,” he wrote.[xviii] Zelensky addressed the Israeli Knesset on March 22, 2022 by sharing a quote from former Israeli prime minister, Golda Meir, who was born in Kyiv: “We intend to remain alive. Our neighbors want to see us dead. This is not a question that leaves much room for compromise.”[xix]

6.16 Statement by [Holocaust] museums on the war crimes committed in Ukraine. Advertisement in The New York Times, Sunday, April 10, 2022.

6.17 Unknown Russian photographer. Babi Yar Ravine, northwest of Kiev, Ukraine where the advancing Red Army unearthed the bodies of 14,000 civilians killed by the Nazis, 1944.

He views Ukraine’s neighbors the same way Jewish Israelis have been forced to view its neighbors: As enemies who seek their erasure. He made it clear that Ukraine would never again rely on anyone else for its security: not the West, not the international community, not the so-called liberal order. The role of the government would be, like Israel, performing the first and foremost role of a free government: answering to the needs of its people and controlling its own destiny.[xx]

As a final photographic point, it should be noted that Western support of Ukraine has initially been buttressed by intense media coverage of the carnage and destruction (with the exception of Fox News), featuring digital photographic images and videos captured and circulated by Ukrainian civilians directly affected by Putin’s military’s barbaric war crimes.[xxi] How long this will continue is doubtful as the media will likely lose interest and move on to a new crisis. Another bitter irony: Germany, who once committed war crimes in Ukraine, has been subsidizing Russia for decades with its dependence on Russian gas. Additionally, Russia has a horrid history of violent antisemitism going back to pogroms beginning in 1881 in Elisavetgrad in the Ukraine. From 1905 onwards the pogroms were primarily organized by the Union of the Russian People, which had government backing. From 1905-1909 pogroms took place in over 184 cities. From these pogroms alone there were an estimated 50,000 victims.

“The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the convinced Communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction (i.e., the reality of experience) and the distinction between the true and the false (i.e., the standards of thought)

no longer exist.”

Hanna Arendt

The Origins of Totalitarianism, 1951, XXXIII

6.18 © Evgeniy Maloletka. Bodies are placed into a mass grave on the outskirts of Mariupol, Ukraine, March 9, 2022.

6.19 © Lynsey Addario. Family killed by Russian mortar fire in the Ukraine, March 6, 2022.

6.20 © James Nachtwey. Nina, Found Dead, 2022.

In terms of ethics, we seek rational explanations for the actions of such bloodthirsty, power-hungry people, but there really are not any because there is no escaping the madness and the meanness of this world, essentially because so many humans tragically embrace the emotional tribalism that authoritarian dictatorships pedal over pluralist democracy, the freedom to define oneself, as championed by leaders like Zelensky.[xxii] It is a reminder that human history never ends, it just rematerializes with aggressive and deadly aggrandizement, as the desire for power over others continues to be an anthropological constant.

Acknowledgements

This ongoing project is flexible and subject to revision as it progresses.

Feedback and suggestions are welcome.

Research assistance by Ruby Merritt

Noteworthy thanks to Lisa Murray-Roselli for her editing expertise.

This theme is supported by the following organizations and individuals:

VASA, Vienna, Austria: Roberto Muffoletto, Director

CEPA Gallery, Buffalo, NY USA: Claire Legget, Interim Director

Galicia Jewish Museum, Kraków, Poland: Tomasz Strug, Deputy Director and Chief Curator

Holocaust Resource Center of Buffalo, Buffalo, NY USA: Elizabeth Schram, Director

Jewish Community Center of Greater Buffalo, Buffalo, NY USA: Katie Wzontek, Cultural Arts Director

6.21 Pieter Bruegel the Elder. The Triumph of Death, 1562—1563. 46 x 64 inches, Oil on panel. Museo Nacional Del Prado, Madrid, Spain.

Endnotes:

[i] See: Dr. Jib Fowles in “Media Violence: Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Juvenile …,” Volume 4 By United States. Congress. Senate. Committee on the Judiciary. Subcommittee on Juvenile Justice, 58-66. https://books.google.com/books?id=2ThN6gj2_cIC&pg=PA58&lpg=PA58&dq=Dr.+Jib+Fowles,+houston&source=bl&ots=gJHM_Ku9VL&sig=ACfU3U2wtvkUW9xGjXcChcb1V9Q93-tXjQ&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiA64vL0Nz2AhWCkYkEHQTdBtIQ6AF6BAgEEAM#v=onepage&q=Dr.%20Jib%20Fowles%2C%20houston&f=false

[ii] Janina Struk, author of Photographing the Holocaust: Interpretations of the Evidence (London and New York: Routledge, 2005), quoted in Rose George, The Ghetto, Less Gritty, www.guiltandpleasure.com/index.php?site=rebootgp&page=gp_article&id=121

[iii] Isabel Kershner, “Nazi Tapes Provide a Chilling Sequel to the Eichmann Trial,” The New York Times, July 4, 2022, www.nytimes.com/2022/07/04/world/middleeast/adolf-eichmann-documentary-israel.html?searchResultPosition=1

[iv] Henryk Ross, cited in Henryk Ross: Łódź Ghetto Album, 155.

[v] Henryk Ross, cited in Henryk Ross: Łódź Ghetto Album, 27.

[vi] Originally written in Yiddish, it was edited for a postwar English speaking audience and transformed from an infuriated historical account into a creative expression as told by a sincere teenager who was overwhelmed with survivor’s guilt and the absence of god.

[vii] Just like hyenas, humans are top predatory animals who at times cooperate and build societies and other times destroy them. See: Ashley Ward. The Social Lives of Animals (New York: Basic Books, 2022).

[viii] Lawrence L. Langer. “The Dilemma of Choice in the Deathcamps,” Centerpoint: A Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, vol. 4, no. 1 (1980), 53–59; reprinted in John K. Roth and Michael Berenbaum, (eds.), Holocaust: Religious and Philosophical Implications (New York: Paragon House, 1989), pp. 222–232.

[ix] Hannah Arendt. Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, (New York: Viking press, 1963), 233.

[x] See: Susan Sontag. Regarding the Pain of Others (New York: Picador – Farrar, Straus and Giroux), 2004.

[xi] See: My Jewish Learning. “Tikkun Olam: Repairing the World.” This phrase with kabbalistic roots has come to connote social justice. www.myjewishlearning.com/article/tikkun-olam-repairing-the-world/

[xii] Antisemitic falsehoods have been a core element of communist ideology and disinformation. See: Juliana Geran Pilon, “Putin’s ‘De-Nazification’ Claim Began With Marx and Stalin,” www.wsj.com/articles/putins-de-nazification-claim-began-with-marx-and-stalin-world-imperialism-russia-soviets-communism-11647032625?mod=opinion_lead_pos6

[xiii] Anton Troianovski, “Putin Aims to Shape a New Generation of Supporters, Through Schools,” July 16, 2022, www.nytimes.com/2022/07/16/world/europe/russia-putin-schools-propaganda-indoctrination.html

[xiv] Melaine Phillips, “For the Jews, history repeats itself in Ukraine,” Jewish News Syndicate, March 3, 2022, www.jns.org/opinion/for-the-jews-history-repeats-itself-in-ukraine/?utm_source=The+Daily+Syndicate&utm_campaign=4a7c96baf1-Daily+Syndicate+02-27-22+%28new%29_COPY_01&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_8583953730-4a7c96baf1-%5BLIST_EMAIL_ID%5D&ct=t%28Daily+Syndicate+02-27-22+%28new%29_COPY_01%29

[xv] Alex Greenberger. “Documenta Head Is Out Amid Anti-Semitism Controversies and Pressure from German Politicians,” ARTnews, July 16, 2022, www.artnews.com/art-news/news/documenta-sabine-schormann-departure-antisemitism-controversies-1234634366/

[xvi] In 2021, Anti-Defamation League (ADL) tabulated 2,717 antisemitic incidents throughout the United States. This is a 34% increase from the 2,026 incidents in 2020. See: www.adl.org/audit2021

[xvii] Cnaan Liphshiz. “In Israel, some Holocaust survivors from Ukraine feel ambivalent about their war-torn country of birth,” Jewish Telegraphic Agency, April 28, 2022, www.jta.org/2022/04/28/global/in-israel-some-holocaust-survivors-from-ukraine-feel-ambivalent-about-their-war-torn-country-of-birth?mpweb=1161-43550-87485

[xviii] “Zelensky urges Jews to shout as Russia ‘erases’ Ukraine: ‘Nazism is born in silence,’” The Times of Israel, March 2, 2022. www.timesofisrael.com/zelensky-urges-jews-to-shout-as-russia-erases-ukraine-nazism-is-born-in-silence/?utm_source=The+Daily+Edition&utm_campaign=daily-edition-2022-03-02&utm_medium=email

[xix] Isabella Kwai, “Walls, Dreams and Genocide: Zelensky’s Speeches Invoke History to Rally Support,” www.nytimes.com/2022/03/21/world/europe/zelensky-speeches-ukraine-russia.html?searchResultPosition=1

[xx] Tovah Lazaroff. “Zelensky: Ukraine will be like Israel, not demilitarized like Switzerland after war,” The Jerusalem Post, April 5, 2022. www.jpost.com/international/article-703335

[xxi] Hannah Allam, “In Ukraine, civilians shape narrative of the war,” The Washington Post, April 8, 2022, www.washingtonpost.com/national-security/2022/04/08/ukraine-war-civilians-witness-narrative/?wpisrc=nl_headlines&carta-url=https%3A%2F%2Fs2.washingtonpost.com%2Fcar-ln-tr%2F368c20d%2F6252aab864253a7f34283891%2F596b0f30ade4e24119acddc4%2F13%2F57%2F6252aab864253a7f34283891

[xxii] Brent Stephens. “Why We Admire Zelensky,” The New York Times, April 19, 2022, www.nytimes.com/2022/04/19/opinion/why-we-admire-zelensky.html

Image Notes:

6.6 Henryk Ross.

6.6 Henryk Ross. Łódź ghetto Jewish police (wearing Star of David arm bands) loading fellow residents into a boxcar bound for death camp, circa 1942—1944. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA.

Caption:

Disguised as a custodian, Ross secretly photographed a crowd of Łódź Jews being herded onto a train of boxcars. Ross recounted: “People with whom I was acquainted worked at the railway station of Radogoszcz, which was outside the ghetto but linked to it, and where trains destined for Auschwitz were standing. On one occasion I managed to get into the railway station in the guise of a cleaner. My friends shut me into a cement storeroom. I was there from six in the morning until seven in the evening, until the Germans went away and the transport departed. I watched as the transport left. I heard shouts. I saw the beatings. I saw how they were shooting at them, how they were murdering them, those who refused. Through a hole in a board of the wall of the storeroom I took several pictures.” Ross’s photograph is not sharp, taken from a distance, behind what appears to be a line of concrete slabs. No German soldiers are in view, just the Jewish ghetto police with their Star of David armbands. See: Greg Cook, “How Henryk Ross Risked His Life To Secretly Photograph Life In A Nazi Ghetto,” WBUR, March 29, 2017. www.wbur.org/news/2017/03/29/henryk-ross-nazi-ghetto

6.9 Henryk Ross.

6.9 Henryk Ross. Ghetto Elite Dancing, 1943. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada.

Caption:

Ross’s photographs of the ghetto elite’s attempts to pretend life was normal contrasted with the post-Holocaust visual narrative of acute suffering. However, close examination of this image reveals that even though the two women in foreground were smiling for the camera, their black teeth expose a lack of dental care and proper nutrition. The expression of gentleman in the suit and tie with the mustache appears melancholy at best. Maybe they did not want to admit it at that moment, but they probably knew they were dancing on the deck of The Titanic, which sunk in 1912 killing around 1,500 of the 2,224 passengers. That said, even in the waiting room of death people seek moments of release. This is reaffirmed by the remarks of the international relations manager of the Lviv National Opera in Ukraine, made as Russian makes unprovoked war on Ukraine: “If people day by day are faced with sad news about death, about blood, about bombs, they need to feel other emotions.” See: Ostap Hromysh, the international relations manager of the Lviv National Opera in Ukraine, which recently resumed limited events with ballet and choir performances even as war ravages the country. “The Quote of the Day,” The New York Times, April 12, 2022, p 3. www.nytimes.com/2022/04/11/todayspaper/quotation-of-the-day-ballets-bars-and-bomb-scares-lviv-learns-to-live-with-war.html

6.10 Henryk Ross.

6.10 Henryk Ross. Łódź Ghetto Folio, page 1, 1940—1945; assembled 1962—1987. 11 x 8 9/16 inches. Gelatin silver prints. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada.

Caption:

Ross’s editing reveals that life is rarely monolithic; it is a complex bundle of contradictions that illuminate the way singular decisions can compound and change over time.

6.11 Unknown photographer.

6.11 Unknown photographer. Henryk Ross testifying in the trial of Adolf Eichmann at the Jerusalem District Court, May 2, 1961. Ghetto Fighters’ House Archives (Itzhak Katzenelson Holocaust and Jewish Resistance Heritage Museum, Documentation and Study Center), Western Galilee, Israel is the world’s first museum commemorating the Holocaust and Jewish heroism.

Caption:

Ross’s photographs were submitted as evidence to help convict Adolf Eichmann. Eichmann was a high-ranking Nazi official who played a central role in the implementation of the Final Solution during the Holocaust. Eichmann organized the deportation of more than 1.5 million Jews from all over Europe to ghettos, killing centers, and killing sites in German-occupied Poland and parts of the occupied Soviet Union. For details see: Eichmann Trial, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/eichmann-trial

6.12 AP wirephoto from signal corps radiophoto.

6.12 AP wirephoto from signal corps radiophoto. General Dwight D. Eisenhower walks around a cluster of bodies of prisoners who were left lying where slain at Ohrdruf, April 12, 1945. Eisenhower Presidential Library, Museum, and Boyhood Home, Abilene, Kansas.

Caption:

General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander, (standing center, hands on hips) gazes at the bodies of dead Russian and Polish internees at the former German concentration camp in Ohrdruf Germany while touring the Third Army front with other Allied Generals.

6.17 Unknown Russian photographer.

6.17 Unknown Russian photographer. Babi Yar Ravine, northwest of Kiev, Ukraine where the advancing Red Army unearthed the bodies of 14,000 civilians killed by the Nazis, 1944.

Caption:

On September 29 and 30, 1941, more than 33,000 Jews were executed by Einsatzgruppe C (mobile killing units) and willing Ukrainian executioners in the Babi Yar ravine – one of the largest mass murders in the Holocaust.

See: Stéphanie Trouillard, “The first major massacre in the ‘Holocaust by bullets:’” Babi Yar, 80 years on,” FRANCE 24, September 29, 2021. www.france24.com/en/europe/20210929-the-first-major-massacre-in-the-holocaust-by-bullets-babi-yar-80-years-on

6.18 © Evgeniy Maloletka.

6.18 © Evgeniy Maloletka. Bodies are placed into a mass grave on the outskirts of Mariupol, Ukraine, March 9, 2022.

Caption:

Evgeniy Maloletka, “Amid heavy shelling, Ukraine’s Mariupol city uses mass grave,” The Washington Post, March 10, 2022. www.washingtonpost.com/world/amid-heavy-shelling-ukraines-mariupol-city-uses-mass-grave/2022/03/10/9ec39dc4-a06b-11ec-9438-255709b6cddc_story.html

6.19 © Lynsey Addario.

6.19 © Lynsey Addario. Family killed by Russian mortar fire in the Ukraine, March 6, 2022.

Caption:

Ukrainian soldiers trying to save a man — the only one of four at that moment who still had a pulse — moments after being hit by a Russian mortar while trying to flee Irpin, near Kyiv. See: Andrew E. Kramer, “They Died by a Bridge in Ukraine. This Is Their Story,” The New York Times, March 9, 2022. www.nytimes.com/2022/03/09/world/europe/ukraine-family-perebyinis-kyiv.html

6.20 © James Nachtwey. Nina, Found Dead, 2022.

6.20 © James Nachtwey. Nina, Found Dead, 2022.

Caption:

In early April 2022, Nina was found dead in the kitchen of her home in Bucha, outside Kyiv, where she had lived with her sister Lyudmyla. Hundreds of such bodies have been discovered in the district. Nachtwey texted his editor: “The barbarity and the senselessness of the Russian onslaught are hard to believe even as I witness them with my own eyes. Bombing and shelling civilian residences, firing tank rounds point-blank into homes and hospitals, murdering noncombatants in militarily occupied areas are all tactics being employed by the Russians in a war that was inflicted on a nonthreatening, neighboring sovereign state…. Ordinary’ people are displaying extraordinary courage and determination, if not downright stubbornness, in the face of tremendous destruction and loss of life.”

See: James Nachtwey, “The Costs of War,” The New Yorker, May 9, 2022, www.newyorker.com/magazine/portfolio/05/09/the-costs-of-war?bxid=5be9e2d224c17c6adf6e147d&cndid=34831695&hasha=47e5dec13b974e588518a71bf31afdc0&hashb=573329092c76f0653725fd88fa9b67a9c0d63f9c&hashc=2224b48914b88a6f2091c8632a432bd13317e086ca181b3d061a915702db8727&esrc=AUTO_OTHER

6.21 Pieter Bruegel the Elder.

6.21 Pieter Bruegel the Elder. The Triumph of Death, 1562—1563. 46 x 64 inches, Oil on panel. Museo Nacional Del Prado, Madrid, Spain.

Caption:

This frightening Christian morality painting depicts an army of skeletons, led by Death, destroying the world of the living who are driven toward a huge casket. Every social class is included; offering no hope of salvation. More at: www.museodelprado.es/en/the-collection/art-work/the-triumph-of-death/d3d82b0b-9bf2-4082-ab04-66ed53196ccc