Return to theme table of content

Return to VJIC table of content

Thread #2

Nazi Photographic Perspectives

© Robert Hirsch 2021

VASA Journal on Images and Culture (VJIC), Theme Editor and Writer

A man said to the universe:

“Sir, I exist!”

“However,” replied the universe,

“The fact has not created in me

A sense of obligation.”

Stephen Crane

Poem from War is Kind, 1900

This thread of Photography and the Holocaust: Then & Now examines the perspective of a few select Nazi photographers and those in their service who made personal and official documents[i] of what they saw happening around the ghettos and concentration camps, and how their images can be interpreted. The next thread will feature the viewpoint of significant Jewish Holocaust photographers such as Mendel Grossman, Fay Shulman, and the Sonderkommando. Note: Additional information about the images can be found at the end of this essay.

Figure 2.1 Hyperinflation in Germany

Unknown photographer. Woman wearing a dress and hat made of German currency, circa 1923.

The cultural, economic, political, psychological situation in post-World War I Germany created an environment in which the Nazis (National Socialist German Workers’ Party) could claim that their fabricated, superior, primordial Aaryan identity gave them the right and the duty to create a super fatherland (Vaterland). This black hole singularity of National Socialism produced mass lunacy, a psychic blind spot[ii] that correlated with the Nazi’s spurious racial hygiene theories,[iii] which gave them a “scientific” rationale for conquering, enslaving, and murdering everyone whom they considered outsiders. The German knack of seeing into the future that produced outstanding achievements in the arts and science was only bested by their ability to look away from the present.

The key issue Nazi Holocaust photography raises is not aesthetic or process oriented, but a communal question: Why do people engage in intolerant and merciless behaviors? Every Nazi Holocaust photograph reflects, at its core, the result of dehumanizing racism—the first step towards authoritarian repression and violence. Antisemitism is a timeless, shapeshifting, multipurpose, scapegoating hatred that transfers the responsibility of ones actions and problems collectively onto Jews. Antisemitism remains such a significant international problem that the German government is currently spending $40 million researching its causes, in order to see what might be done to diminish it.[iv] Additionally, the European Commission has reserved $28 million (24 million euros) to heighten protection around already guarded synagogues and other Jewish events or sites.[v]

Figure 2.2 Palestinian rioters near Evyatar outpost put up flaming swastika, 2021.

Abduallah Bahsh/Quds News Network/Screenshot.

This installment inspects Holocaust photography made from the point of view of the perpetrators reenforcing the premise that every photograph made by a German, whether a common soldier or civilian, is about death and the insanity of seeking perfection through delusion. Each of these photographs has an embedded subtext of complicity—causing harm directly or indirectly by being involved in the unmerited wrongdoing of others. Their small, individual, self-serving actions and nonactions are what made the collective depravity of the Holocaust possible.

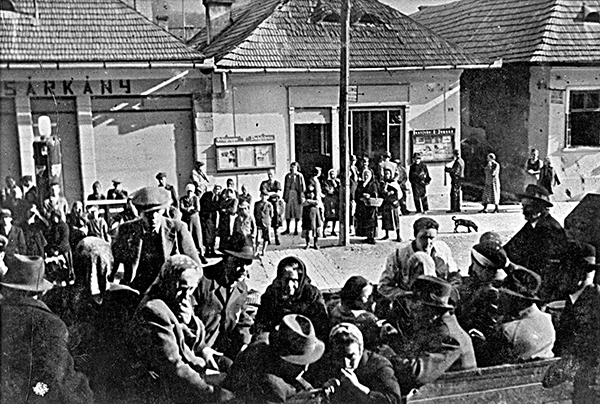

Figure 2.3 Public Deportation of Jews, Dobsina, Gemer, Slovakia, Czechoslovakia, circa 1942.

Unknown photographer. Vad Vashem, Jerusalem, Israel. (https://photos.yadvashem.org/)

Heinrich Joest (aka Heinrich Jost) was a German soldier stationed in Poland who decided to spend his 43rd birthday taking “tourist” pictures in Warsaw. Joest openly defied the German Army’s prohibition of photographing the Jews imprisoned inside the Warsaw ghetto’s 10-foot-high walls. On Sept. 9, 1941, he made 129 photographs, including images of starving and dead children in the street, while walking in uniform, with his Rollieflex camera. Joest even came across Jews he knew, but did not photograph them. In a number of photographs, he recorded another German soldier buying items at bargain prices from desperate Jews who needed money for black market food and coal. He did not show his “sightseer” photographs to anyone until shortly before his death when he gave them to Günther Schwarberg of the German magazine Der Stern. In comments to Schwarberg, Joest said: “In my letters home I didn’t say anything about what I’d seen. I didn’t want to upset my family. I thought, ‘What sort of a world is this?’ I didn’t tell my comrades anything either. Later on, when they burned down the ghetto, we didn’t pay any attention.”[vi] Der Stern declined to publish any of the photographs, but in 1987, turned them over to the Yad Vashem Museum in Israel.

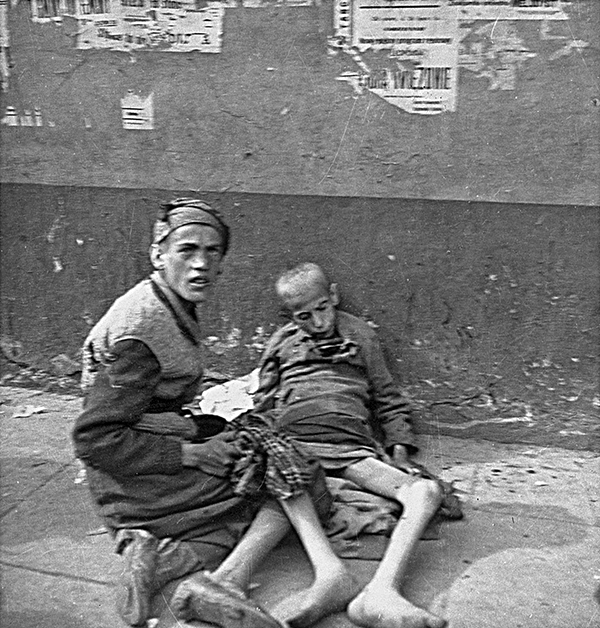

Figure 2.4 A destitute little girl comforts her little sister, who lies unconscious in her lap, 1941. Heinrich Joest. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC.

Joest’s raw photographs provide a candid, gut-wrenching record of ghetto prisoners suffering from extreme lack of housing, food, medicine, or sanitation and offer a tragic foreshadowing to what would befall the 500,000 Polish Jews locked up in a 2.4-square-mile area. In all likelihood, every person in every photograph was eventually gassed. Psychologically, why would a middle-aged man want to spend his birthday photographing a nonstop horror show of death? It would have been highly unusual for anyone at that time to spend the money for film, developing, and printing for so many photographs on any subject. Was Joest curious? Was he fascinated by the walking dead? Did Joest realize he was making photographs from a position of authority and his subjects were powerless to object? Did his own photographs make him contemplate his role in this abominable undertaking? In hindsight, Joest’s direct photographs serve as a record of how German soldiers were able to compartmentalize the conformist, uncritical behavior that made the Holocaust possible.[vii]

The subtext in Joest’s photographs is the abject failure of moral and political imagination, and act as reminders that choice is a precondition for morality. The images are exemplars of how groups of people (countries) that promote displays of rigid cultural and moral viewpoints, tend to be publicly cruel and privately corrupt. In any case, such unofficial photographs record the holistic disconnect between the glorious, imaginary Aryan world and its ruthless, oppressive reality. They also spotlight the rift between experiencing something and having an empathetic connection to what is actually happening.

Figure 2.5 Two young women, one of whom is unconscious, on the street in the Warsaw Ghetto, 1941. Heinrich Joest. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC.

Figure 2.6. An undertaker in the Warsaw ghetto’s Jewish cemetery on Okopowa Street lifts the body of a woman for Heinrich Joest to show him how little it weighs, 1941. Heinrich Joest. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC.

Joe Julius Heydecker, a German author and journalist, was ordered into Warsaw to join a propaganda unit. Anti-Nazi in outlook, Heydecker used a Kine Exakta, one of first successful 35mm single lens reflex cameras, to secretly take hundreds of photographs in the Warsaw Ghetto in spite of a 1941 Nazi prohibition against independent photographers. As a result of his mindset and professional training, his photographs are better composed and not as unrefined and harsh as Joest’s, yet still convey a sense of abandonment and dreadful suffering. With the assistance of friends in his military unit and his wife, his film was kept safe even when the Gestapo raided his home. Later they were used as evidence in the Nuremberg trials and he was one of the few German journalists to report on the trials. After the war, Heydecker spoke on German radio about the atrocities he had witnessed. Even so, Heydecker claimed to be troubled by guilt, shame, and a sense of helplessness for not doing anything to help the ghettoized Jews. Eventually, he published his photographs in 1981.[viii]

In On Photography (1977) Susan Sontag wrote that photographs“…help people to take possession of space in which they are insecure” and that photography could also be a way of “refusing experience.”[ix] Is it possible that such deliberate, unofficial photographs were attempts of denial? Maybe that by abstracting and pushing the Ghettos from their present lives these Germans were Pandoras in reverse, capturing the evil in front of them and safely securing it? Is it conceivable that the fear of unleashing such malignant forces again is why they delayed making their work public or was it just shame?

Figure 2.7 Jewish Boy Sitting on Steps, Warsaw Ghetto, circa 1941. Joe Julius Heydecker. Vad Vashem, Jerusalem, Israel.

In contrast, the intent of The Stroop Report[x] was clear. It was an official document prepared by General Jürgen Stroop for the SS (Schutzstaffel)[xi] chief Heinrich Himmler, recounting the German suppression of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising and the liquidation of the ghetto in the spring of 1943. Originally titled The Jewish Quarter of Warsaw Is No More! (Es gibt keinen jüdischen Wohnbezirk in Warschau mehr!), it was made as a “souvenir album” for Himmler. It was presented by the chief U.S. prosecutor Robert H. Jackson at The International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg in 1946 during his opening address. The assistant prosecutor who was addressing the persecution of the Jews referred to it as “the finest example of ornate German craftsmanship, leather bound, profusely illustrated [53 high-quality photographs plus additional photos that not included in the report], typed on heavy bond paper, the almost unbelievable recital of the proud accomplishment by Major General of Police Stroop.”[xii] Aside from a dozen photographs clandestinely taken by Polish firefighter Leszek Grzywaczewski, the Stroop photographs are the only photos known to have been taken during the Ghetto Uprising.[xiii]

The unnamed photographers were allowed close to combat areas, recording Jews as they were captured from underground hiding places, and buildings that were set on fire and demolished. The album also features photos of Stroop in action— demonstrating a craving to enthusiastically display his cruel, sadistic nature to his superiors, saying look what a fine job I did eliminating these “bandits” and dregs of humanity. Finally, Stroop’s short descriptive captions reflect his Nazi, racist urge to obliterate Jewish culture, property, and life. After the Nazi defeat, his own report delivers a staggering visual testimony to his own role and that of his men in the horrendous end of the Warsaw ghetto.[xiv]

Figure 2.8 The Stroop Report: These bandits offered armed resistance (original caption), 1943. Unknown photographer. Vad Vashem, Jerusalem, Israel.

At first glance, Karl Höcker’s photo album appears to contain snapshots of German soldiers enjoying themselves on leave.[xv] SS-Obersturmführer Höcker was the adjutant to the commandant of Auschwitz from May 1944 until the evacuation of the camp in January 1945.[xvi] The photographs were taken at Solahütte, an SS resort about 18 miles/30 km south of Auschwitz. Archival records disclose that the SS incentivized Auschwitz guards for doing exceptional work with a getaway to Solahütte. This “vacationer” album was made when the Auschwitz gas chambers were operating at their peak as more than 424,000 Hungarian Jews arrived over an eight-week period.[xvii]

Figure 2.9 An accordionist leads a sing-along for SS officers at their retreat at Solahuette outside Auschwitz, 1944. Unknown photographer. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC.

One disturbing photograph records an accordionist leading a sing-along for some 70 SS men. In the front row of the group are Höcker, SS-Hauptscharführer Otto Moll (the supervisor of the gas chambers), Höss, Baer, Kramer, Franz Hössler (commander of the female prisoner compound at Birkenau), and the “Angel of Death” himself, Dr. Josef Mengele. At the time this photograph was made the Germans knew the war was lost and still chose to continue their homicidal ways.

A group of six photographs entitled Hier gibt es Blaubeeren (Here There are Blueberries) shows Höcker, who had just given bowls of fresh blueberries to twelve SS Helferinnen women sitting on a fence. They reciprocate by melodramatically overturning their empty bowls. The fifth woman from the left even produces mock tears in gratitude as the accordionist (barely visible in the right side of the frame) plays, while another Nazi relaxes in a lounge chair. That same day, 150 prisoners (Jews and non-Jews) arrived at Auschwitz. The SS selected 21 men and 12 women for work and immediately exterminated the others in the gas chambers.

Figure 2.10 Members of the SS Helferinnen (female auxiliaries) and SS officer Karl Höcker invert their empty bowls to show they have eaten all their blueberries, 1944.

Unknown photographer. Auschwitz Album, 1944. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC.

Such photographs, in a classic snapshot style, enshrine their “family values” and good-time memories, but here they raise the specter of unseen demons outside the camera’s frame: how could these people commit robbery and mass murder[xviii] and then picnic on the same day? One possibility is that they considered themselves to be godlike, entitled to impose their will on the earth while being oblivious to the suffering of others. Anyone outside of their realm did not exist except as data collection points—a component of the Nazi obsession with record keeping— redundant flunkies or slaves in terra incognito. These images capture an unknown place filled with Untermensch—racially and socially inferior monsters whose persecution had reduced them to tatters.

The only other known photo album from Auschwitz (published as the Auschwitz Album in 1980), specifically depicts the arrival of the Hungarian Jews and the SS’s life and death selection process.[xix] The staged photographs were taken in May 1944, probably over the course of two days, by Ernst Hofmann and/or Bernhard Walter, SS men who took ID photos and fingerprints of the brutalized inmates who were not sent directly to the gas chambers—another coercive, humiliating measure imposed on prisoners. The album’s 56 pages contain 193 photographs capturing the “selection” process on the “Ramp” of life and death. On the Ramp, those sent to the right were immediately gassed and those directed left were selected as slave labor. What is not shown is the intimidation, threats, and violence the SS used on the Ramp and everywhere else they roamed, nor the gassing and burning of bodies, giving the intentionally false impression this was a smooth operation and that the people were not resisting.

Figure 2.11 Jewish women and children from Subcarpathian Rus await selection on the ramp at Auschwitz-Birkenau, 1944. Ernst Hofmann or Bernhard Walter. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC.

Why the album was made is unknown. One can speculate it was produced as an official record for higher level Nazis, as were photo albums from other concentration camps, and to testify to their zest for looting, slavery, and genocide,[xx] with the ultimate goal of creating the Aryan Übermensch—the superior person, who justifies the existence of the human race,[xxi] by means of collaborative murder.[xxii]

Figure 2.12 Jewish brothers from Subcarpathian Rus await selection on the ramp at Auschwitz-Birkenau, 1944. Ernst Hofmann or Bernhard Walter. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC.

All of these albums selectively organize and transform actions into memories. They wanted these events to be remembered in a positive way, creating a narrative to be shared with their colleagues in the future. Instead, the Auschwitz photographs have become the central photographic symbols of unrepresentable genocide. This points out how photographs can contain a specific, but highly contrary, intent and viewpoint. For the Germans they proclaimed: Look what we did to those racially, socially, and physically defective untermenschen. Their casualties see these photographs as: Look at how they tried to destroy our humanity. Photographic interpretation is dependent upon point-of-view and knowledge outside the photographic frame, without which, one would not comprehend what was happening.[xxiii]

Figure 2.13 SS officer Karl Hoecker lights a candle on a Christmas tree only weeks before the liberation of Auschwitz, 1944.

Unknown photographer. Auschwitz Album, 1944. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC.

For the Germans who once cheered at Nuremberg, the Auschwitz photographs contain the stark reminder of their complicit tribal madness, which resulted in some 17 million people being murdered[xxiv] in about 27 main concentration camps and at least 1,100 satellite camps.[xxv] Yet, the Germans were collectively able to look away, claiming to know nothing about these prisons even though numerous German soldiers, police, and civilians made photographs of the actions that were part of the Holocaust.[xxvi] Anthropologically, the Auschwitz photographs represent an individual’s ability to pretend, to rationalize, and deny the reality of innate human cruelty for the sake of domination and greed—stealing and selling their belongings, property, hair, their ground up bones, and skin,[xxvii] while professing that everything is normal. After their defeat, most Germans and their willing accomplices resumed their lives in business, government, industry, and at home as if nothing unusual ever happened, seemingly unphased by their moral and spiritual delinquencies.

Figure 2.14 German guards and Ukrainian militia shooting a Jewish family in Miropol, Ukraine, 1941. Lubomir Skrovina. Security Services Archive.

In her book, The Ravine: A Family, a Photograph, a Holocaust Massacre Revealed (2021) Wendy Lower details how an entire town killed their Jews. There were gunshots, “yelling, screaming and howling.” This was not the bureaucratic killing but mass murder at its most intimate: The Ukrainians “taunted the victims by name.… The victims were known to them from the dentist’s office, the cobbler’s shop, the soda fountain and the collective farm. They grabbed small children and babies by the legs and smashed their heads against the trees.” There were Ukrainian teenage girls forced to dig mass graves; Nazi customs guards and volunteers, along with Ukrainian policemen, rounded up the Jews and forced them to the death site; Ukrainian neighbors plundered their homes and “assaulted them—throwing stones and bottles.” Then there were the Ukrainian militia who, “armed with clubs, tools and Russian rifles, chased Jews, bludgeoning some to death.… They chased young Jewish women, ripped off their clothes and raped them.” Every single person in Miropol knew what had taken place. See: Wendy Lower. The Ravine: A Family, a Photograph, a Holocaust Massacre Revealed (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2021).

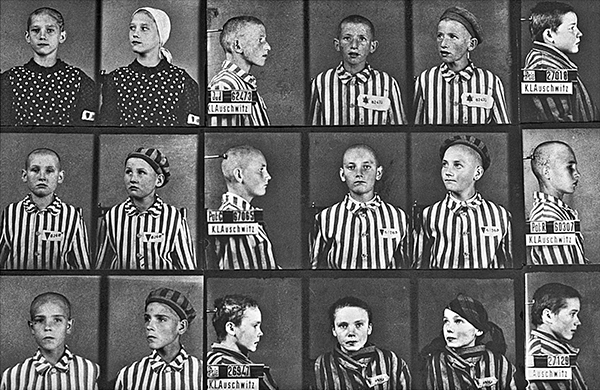

The Auschwitz photographs also point out that images alone, with their fluid meaning dependent on context and personal interpretation, are not enough to change one’s beliefs in the Master Race.[xxviii] Relying on their position of power, the overlord concentration camp mugs shot (aka identity picture) photographers utilized photography’s specificity to reinforce the Nazi’s pseudo-scientific, racist system of biometric measurements to identify untermenschen (subhuman, disgusting, inferior people). Proclaiming their superiority, they set out to eliminate all the Others.[xxix]

Figure 2.15 Children Auschwitz Mugshots, circa 1943-1944. Attributed to Wilhelm Brasse. Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, Oświęcim, Poland.

Wilhelm Brasse was a Polish professional photographer and a prisoner in Auschwitz who was assigned to photograph camp events, including medical experiments.[xxx] Brasse estimated that he took 40,000 to 50,000 “identity pictures” from 1940 until being liberated in 1945.[xxxi] The mug shots were part of the Nazi’s systematized machinery that reduced its victims to objects, meant to encourage them to collude in their own victimization as they could see no other options. These photographs are visual symbols of the totalitarian aim to transform and control society by being an oppressive, pervasive presence, stamping out difference in every aspect of human life. Mugshots represent authority: there is a jailer and a prisoner. It is assumed that the prisoner has done something wrong, which is why the person is being incarcerated and punished. Taken during a moment of crisis and despair, these mugshots, made after the individuals had been dispossessed, stripped, shaved, and tattooed, serve as stilted collections of punitive biometric data, re-enforcing the notion that these were not people but numbers in a ledger book. They serve as what sociologist Michelle Brown calls “penal spectatorship”—ways of looking at arrested and imprisoned people as guilty and deserving of punishment.[xxxii]

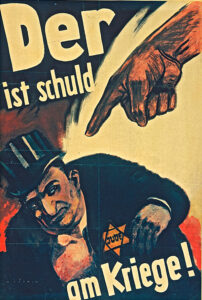

Figure 2.16 He is to blame for the war! Mjölnir [Hans Schweitzer], 1943. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

This raises the issue of whether a photograph, with its overabundance of data, is just a trace of the world or whether it could be the result of empirical reason? What scholars have concluded is that none of our beliefs, rational or otherwise, rely much on logical reasoning. Instead, we cherry-pick and rationalize what we absorb from the world to conform to our emotional preconceptions.[xxxiv] Nevertheless, bearing witness with visual proof from the lenses of the perpetrators point is one reason why Holocaust photographs should remain in the public arena.

Beneath the sorrow of the families and future generations of those who were murdered,[xxxv] the Auschwitz photographs are about injustice, which evokes RAGE. RAGE against the silence of the Christian nations,[xxxvi] of the world that allowed the Holocaust to happen and did little or nothing to stop it. Rage against the Nazi’s tyrannical racial-cleansing philosophy of annihilation that wiped out Jewish European society, that believed the only good Jew is a dead Jew. Rage against the totalitarian, fear-based avatar of evil with its own corrupt and distorted laws and justice system. Rage against the senseless societal destruction of Yiddish culture (85% of the murdered were Yiddish speakers) and the ferocious annexation of artistic and cultural spheres. Rage against the doctors and pseudo scientists experimenting on human beings to prove their sham eugenic theory of a patriarchal master race. Rage against the selfish violence and terror of one’s neighbors who expressed no empathy or emotional intelligence. Rage against how the majority of the brutal culprits were never brought to justice. Rage against the ossified rejection of participation and the embrace of Holocaust distortion, denial,[xxxvii] and false revisionist history.[xxxviii] And RAGE that over time these Holocaust photographs have done little to stem hate[xxxix] against a tiny minority.[xl]

Figure 2.17 Hungarian Jews at entrance to the Auschwitz “showers” gas chamber, 1944. Unknown photographer. Auschwitz Album, 1944. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum,Washington, DC.

Finally, what these Nazi photographs indicate is that, given certain circumstances, humans and their national constructs make terrible, long-term decisions and few resist. As one absorbs these Nazi photographs, what one eventually sees is oneself, raising the unanswerable questions: Who would you be and what would you do?

Afterward

This ongoing project is flexible and subject to revision as it moves forward.

Feedback and suggestions are welcome.

Special thanks to Mark Jacobs and Gary Nickard, PhD for their editorial input.

Noteworthy gratitude to Lisa Murray for her copy-editing expertise.

[i] These photographs are direct transcriptions of visual facts – what was facing the camera lens that were conventionally processed without any post-capture manipulation.

[ii] See: Benjamín Labatut, Translated by Adrian Nathan West. When We Cease to Understand the World (New York: New York Review Books, 2021).

[iii] See: Nazi Medical Experiments, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/nazi-medical-experiments. These so-called experiments have their roots in the biological determinist ideas of Sir Francis Galton, which originated in the 1880s and took hold in political, social, and scientific agendas in the US through the mid-twentieth century. Their goal was to eliminate those they deemed unfit for society that included the disabled, the mentally ill, the poor, and people of color.Eugenicists launched sterilization initiatives that targeted African American, Hispanic, and Native American women.

[iv] Sharon Wrobel. “German Government to Spend $40 Million on Researching What Fuels Antisemitism, Racism,” The Algemeiner, August 4, 2021, www.algemeiner.com/2021/08/04/german-government-to-spend-40-million-on-researching-what-fuels-antisemitism-racism/

[v] Melissa Eddy. “Nine Barrack at Auschwitz Are Tagged with Antisemitic Slurs by Vandals” The New York Times, October 6, 2021. www.nytimes.com/2021/10/06/world/europe/auschwitz-antisemitism-graffiti.html

[vi] Günther Schwarberg (ed). In The Ghetto Of Warsaw: Photographs by Heinrich Jost (Göttingen, Germany: Steidl Verlag, 2001), unp.

[vii] Some of Jost’s photographs can be viewed at: https://steemit.com/photography/@raclariu/a-day-in-the-warsaw-ghetto-rare-pictures-by-heinz-joest

[viii] Joe J. Heydecker .Where is thy brother Abel? Documentary Photographs of the Warsaw Ghetto (São Paulo: Atlantis Livros, 1981). Some images are available at: www.rferl.org/a/ghetto-warsaw-poland-jude/24960526.html

[ix] Susan Sontag. On Photography (New York: Farr, Straus and Giroux, 1977), 177.

[x] See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stroop_Report

[xi] See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Schutzstaffel and https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/ss

[xii] Robert E. Conot. Justice at Nuremberg, (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 1983), pp. 269-70.

[xiii] On the back of one of his photographs Grzywaczewski commented on his powerlessness at being under German command as he watched people jumping out of windows to their deaths: “We weren’t able to help them although [we had] the technical ability.” Other fireman helped the SS round up Jews. See: http://somewereneighbors.ushmm.org/#/exhibitions/policemen/un1709/description

[xiv] See: www.yadvashem.org/yv/en/exhibitions/warsaw_ghetto/collection.asp

[xv] See: www.ushmm.org/collections/the-museums-collections/collections-highlights/auschwitz-ssalbum

[xvi] “Auschwitz,” https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/auschwitz

[xvii] See: https://www.yadvashem.org/holocaust/about/fate-of-jews/hungary.html

[xviii] Stolen belonging were stored in warehouses nicknamed “Kanada” by the inmates because they saw them as the land of plenty.

[xix] https://www.yadvashem.org/yv/en/exhibitions/album_auschwitz/arrival.asp

[xx] Genocide is an internationally recognized crime where acts are committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group. The word “genocide” is a very specific term coined by Polish-Jewish lawyer Raphael Lemkin (1900–1959) in 1944 to describe Nazi policies of systematic murder during the Holocaust, including the destruction of European Jews. Lemkin devised the word by combining geno-, from the Greek word for race or tribe, with -cide, from the Latin word for killing. More at: www.ushmm.org/genocide-prevention/learn-about-genocide-and-other-mass-atrocities/what-is-genocide

[xxi] See: Friedrich Nietzsche. Thus Spoke Zarathustra: A Book for All and None, (1883).The Nazis unrecognizably twisted Nietzsche’s allegorical meaning to their regressive ends.

[xxii] There is no evidence that any member of the Axis forces, men or women, young or old, were made to murder by the Germans. See: Christopher R. Browning. Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland (New York: Harper Perennial, 1993). Wendy Lower. Hitler’s Furies: German Women in the Nazi Killing Fields (Boston & New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2013).

[xxiii] Tal Bruttmann. “Analysing Holocaust Photography: The Auschwitz Album,” www.youtube.com/watch?v=gRvxkyzjCZM

[xxiv] www.statista.com/chart/24024/number-of-victims-nazi-regime/

[xxv] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nazi_concentration_camps Also, between 1933 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its allies established thousands of camps and other incarceration sites (including ghettos). The perpetrators used these sites for a range of purposes, including forced labor, detention of people thought to be enemies of the state, and for mass murder. See: https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/nazi-camps

[xxvi] “Ex-Nazi camp guard tells German court he is innocent, insists he ‘knows nothing’” http://www.timesofisrael.com/ex-nazi-camp-guard-tells-german-court-he-is-innocent-insists-he-knows-nothing/?utm_source=The+Daily+Edition&utm_campaign=daily-edition-2021-10-08&utm_medium=email

[xxvii] “Researchers find Nazi photo album bound with human skin,” www.timesofisrael.com/researchers-find-nazi-photo-album-bound-with-human-skin/

[xxviii] In Luke Holland’s film, Final Account (2021), the past speaks to the present as Holland interviews former Nazi functionaries from Hitler’s Third Reich as they evoke denial, evasion, and self-justification regarding their actions. It is a bleak reminder that the past is appallingly adjacent to the present. See: https://newrepublic.com/article/162252/holocaust-nazi-documentary-final-account-review

[xxix] The SS planned to set up a Jewish Museum in Prague with confiscated cultural and devotional objects and staffed by experts, in anticipation of the coming time when the Jewish people would be in the dustbin of history. See: www.jewishmuseum.cz/en/info/about-us/history-of-the-museum/

[xxx] See: Luca Crippa & Maurizio Onnis. The Auschwitz Photographer: The Forgotten Story of the WW II Prisoner Who Documented Thousands of Lost Souls (Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks, 2021).

[xxxi] See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wilhelm_Brasse

[xxxii] Michelle Brow. The Culture of Punishment: Prison, Society, and Spectacle (New York: New York University Press, 2009). Intro.

[xxxiii] Henryk M. Broder. Der ewige Antisemit. Kapitel 5: Der Täter als Bewährungshelfer oder Die Deutschen werden den Juden Auschwitz nie verzeihen (Frankfurt/Main: Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag, 1986), p. 130.

[xxxiv] See William J. Bernstein. The Delusions Of Crowds: Why People Go Mad in Groups (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2021). Also, “Why false narratives so often trump reality,” www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/why-false-narratives-so-often-trump-reality/2021/02/24/9678ad5c-64db-11eb-8c64-9595888caa15_story.html

[xxxv] Victims include Gypsies, Jehovah’s Witnesses, homosexuals, Blacks, the physically and mentally disabled, political opponents of the Nazis, including Communists and Social Democrats, dissenting clergy, resistance fighters, prisoners of war, Slavic peoples, and individuals from the artistic communities whose opinions and works Hitler condemned. See: Susan Bachrach, Tell Them We Remember: The Story of the Holocaust (Boston: Little Brown, 1995), 20.

[xxxvi] Gerard S. Sloyan. “Christian Persecution of Jews over the Centuries” https://www.ushmm.org/research/about-the-mandel-center/initiatives/ethics-religion-holocaust/articles-and-resources/christian-persecution-of-jews-over-the-centuries/christian-persecution-of-jews-over-the-centuries

[xxxvii] “Poland Passes Controversial Restitution Law, Sparking International Outcry,” www.artnews.com/art-news/news/poland-restitution-law-outcry-israel-united-states-1234601640/

[xxxviii] Holocaust Denial: www.museumoftolerance.com/education/teacher-resources/holocaust-resources/what-is-holocaust-denial.html and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Holocaust_denial

[xxxix] See: “State of Antisemitism in America 2020” at: www.ajc.org/AntisemitismReport2020 and “Experiences and perceptions of antisemitism – Second survey on discrimination and hate crime against Jews in the EU” at: https://fra.europa.eu/en/publication/2018/experiences-and-perceptions-antisemitism-second-survey-discrimination-and-hate Also, the FBI’s 2020 Hate crime statistics show that of all US hate crimes motivated by religion, 57.5% targeted Jews. See: www.fbi.gov/news/pressrel/press-releases/fbi-releases-2020-hate-crime-statistics

[xl] Jews make up about 2.4% of the US population, yet are not officially recognized as a minority group in the US. See: www.pewforum.org/2021/05/11/the-size-of-the-u-s-jewish-population/ Jews in Europe make up about 0.1% of the continent’s population. See: www.theguardian.com/world/2020/oct/25/europes-jewish-population-has-dropped-60-in-last-50-years Jews represent about 0.2% of the worldwide population. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jewish_population_by_country

Additional information on figures

Figure 2.1 Hyperinflation in Germany

Figure 2.1

Unknown photographer. Woman wearing a dress and hat made of German currency, circa 1923.

Caption: Hyperinflation affected the German Papiermark, the currency of the Weimar Republic, between 1921 and 1923. It caused considerable internal political instability and misery for the general populace. In addition, the occupation of the Ruhr by France and Belgium provided Hitler with much to exploit and the ability to place blame. The destruction of the middle class’s savings led to scenes like this of a woman wearing a dress and hat made of cash and children playing with stacks of worthless legal tender as if they were toy bricks. At one stage, 4.2 trillion German marks were worth a mere one American dollar. More at: www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-5088405/When-cash-worthless-Germany-World-War.html

Figure 2.2 Palestinian rioters near Evyatar outpost put up flaming swastika, 2021.

Figure 2.2

Abduallah Bahsh/Quds News Network/Screenshot.

Caption: Palestinian rioters threw explosives, burned tires, and pointed laser lights during the nightly riots, which began before the outpost was evacuated. The image is striking for its virulent antisemitism and its silence. They also burned an effigy of a religious Jew with a payot (sidelocks). Now imagine if the swastika were a cross and the effigy was of a Christian priest. ww.jpost.com/breaking-news/rioters-near-evyatar-outpost-put-up-flaming-swastika-676724

Figure 2.3 Public Deportation of Jews, Dobsina, Gemer, Slovakia, Czechoslovakia, circa 1942.

Figure 2.3

Unknown photographer. Vad Vashem, Jerusalem, Israel. (https://photos.yadvashem.org/)

Caption: The Nuremberg Racial Laws of 1935 robbed the Jewish population of most of their civil and property rights. Jews were forced to wear a yellow star and bear the first names “Sara” or “Israel.” Their assets and shops were “Aryanised” by the Germans and locals who would then take over the possessions and properties of the vanquished. In this seemingly mundane photograph, context is everything—local Jews were publicly rounded up and deported to Auschwitz as their neighbors watched. Some 100,000 Slovak Jews were murdered in the Holocaust. Vad Vashem has thousands of photographs depicting scenes like this throughout German-occupied Europe. The witnesses would later claim: ‘We had no idea this was happening.’

Figure 2.4 A destitute little girl comforts her little sister, who lies unconscious in her lap, 1941.

Figure 2.4

Heinrich Joest. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC.

Caption: Joest’s original caption reads: “These were clearly sisters. If the younger one was dead, I could not say. She did not move.” Photographs at: www.ushmm.org/search/results.php?q=Heinrich+joest&q__src=&q__grp=&q__typ=&q__mty=

Figure 2.5 Two young women, one of whom is unconscious, on the street in the Warsaw Ghetto, 1941.

Figure 2.5

Heinrich Joest. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC.

Caption: Joest’s original caption reads: “Under ripped advertisements an unconscious woman lay against the wall. Another person attempted to care for her. She looked at me as if she expected me to help” (emphasis added).

Figure 2.6

Figure 2.6.

An undertaker in the Warsaw ghetto’s Jewish cemetery on Okopowa Street lifts the body of a woman for Heinrich Joest to show him how little it weighs, 1941. Heinrich Joest. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC.

Caption: Joest’s caption reads: “The dead were not heavy, as one corpse-bearer showed me – although I had not asked him to – in front of the buildings of the Jewish cemetery.”

Figure 2.7 Jewish Boy Sitting on Steps, Warsaw Ghetto, circa 1941.

Figure 2.7

Joe Julius Heydecker. Vad Vashem, Jerusalem, Israel.

Caption: In the book of this work, Where is thy brother Abel? Documentary Photographs of the Warsaw Ghetto (1981) Heydecker wrote: “I find it hard to explain why nearly forty years have passed before I was able to publish these pictures. I believe I simply had not strength enough to write the text, although I tried several times. I still feel unable to do so. Now I do what I can to set down what is seared into my memory, weak as it may be, because time is running out.”

Figure 2.8 The Stroop Report: These bandits offered armed resistance (original caption), 1943.

Figure 2.8

Unknown photographer. Vad Vashem, Jerusalem, Israel.

Caption: This photograph was taken by a German photographer at Nowolipie Street looking east, near intersection with Smocza Street. In the background, a ghetto wall with a gate can be seen. Jewish women and men took part in resistance fighting. The woman to the right is Hasia Szylgold-Szpiro, who appears stoically defiant. The woman in the center has no shoes and all appear to have been living in dreadful conditions. The insurgents’ defiance surprised the Germans and continued for a month. They used any means possible including incendiary bottles and grenades. Unable to quell the rebellion, the Germans, with the help of Ukrainians and Latvians, burned down all the buildings in the so-called “closed district.” Using cannons and machines guns, the executioners timed the Ghetto massacre to coincide with the Jewish holiday of Passover and as a “gift” for the Führer’s birthday.

Figure 2.9 An accordionist leads a sing-along for SS officers at their retreat at Solahuette outside Auschwitz, 1944.

Figure 2.9

Unknown photographer. Auschwitz Album, 1944. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC.

Caption: Pictured in the front row are Karl Hoecker, Otto Moll, Rudolf Hoess, Richard Baer, Josef Kramer (standing slightly behind Hoessler and partially obscured), Franz Hoessler, Josef Mengele, Anton Thumann, and Walter Schmidetzki. Hermann Buch is in the center. Konrad Wiegand, head of the Fahrbereitschaft (car and truck pool) is in the middle. Based on the officers visiting Solahutte, it is surmised that the photographs were taken to honor Rudolf Hoess, who completed his murderous tenure as garrison senior on July 29, 1944.

Figure 2.10 Members of the SS Helferinnen (female auxiliaries) and SS officer Karl Höcker invert their empty bowls to show they have eaten all their blueberries, 1944.

Figure 2.10

Unknown photographer. Auschwitz Album, 1944. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC.

Figure 2.11 Jewish women and children from Subcarpathian Rus await selection on the ramp at Auschwitz-Birkenau, 1944.

Figure 2.11

Ernst Hofmann or Bernhard Walter. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC.

Caption: In contrast to fun-loving SS Helferinnen, previously pictured at Solahutte, among those already abused civilians are Irina Berkovits (age 37) and her son Adalbert (age 5); both perished. Also pictured are Hajnal Klein and her four daughters Lili (age 18), Herczi (age 15), Renee (age 12) and Iren (age 7). Hajnal, Renee and Iren were killed upon arrival. Lili and Herczi survived.

Figure 2.12 Jewish brothers from Subcarpathian Rus await selection on the ramp at Auschwitz-Birkenau, 1944.

Figure 2.12

Ernst Hofmann or Bernhard Walter. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC.

Caption: Pictured are Israel and Zelig Jacob, aged nine and eleven. They were gassed shortly after arrival.

Figure 2.13 SS officer Karl Hoecker lights a candle on a Christmas tree only weeks before the liberation of Auschwitz, 1944.

Figure 2.13

Unknown photographer. Auschwitz Album, 1944. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC.

Caption: The original caption reads: “Julfeier 1944” (the Nazi name for a pre-Christian Yule celebration).

Figure 2.14 German guards and Ukrainian militia shooting a Jewish family in Miropol, Ukraine, 1941.

Figure 2.14

Lubomir Skrovina. Security Services Archive.

Caption: Lubomir Skrovina was an exceptional Slovakian soldier who took this photograph with the full knowledge of his German superiors. However, unlike most of the willing executioners he did not take it in service of the Germans. Skrovina joined the Resistance and took this photograph as an act of defiance. He smuggled such cold-blooded, merciless images back home to his wife for use by the anti-Nazi forces. Later, he was released from further military duty; hid Jews in his home; helped some escape; and allied with the antifascist Slovakian uprising of 1944.

Figure 2.15 Children Auschwitz Mugshots, circa 1943-1944.

Figure 2.15

Attributed to Wilhelm Brasse. Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, Oświęcim, Poland.

This attitude led Polish-born German journalist and author Henryk Marcin Broder to write with bitter irony: “The Germans will never forgive the Jews for Auschwitz.”[xxxiii] A broadening to this observation is that many Europeans continue to blame the Jews, and now the Israelis, for Auschwitz. Broder’s defiant observation reflects the view that some Germans and their likeminded confederates want to free themselves from responsibility for Nazism. They wish to turn history upside down and inside out and present themselves as “victims” and blame the Jews for the Holocaust.

Figure 2.16 He is to blame for the war!

Figure 2.16

Mjölnir [Hans Schweitzer], 1943. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Caption: The Nazis sought to provoke hatred of Germany’s Jews by transforming the popular perception of them from fellow citizens into domestic, back-stabbing enemies guilty of warmongering and betraying Germany from within. It made no difference that many Jews considered themselves to be full-fledged German citizens who made major contributions in German culture and science, including multiple Nobel Prize winners. The result was an exodus of some 2,600 Jewish scientists from Germany to Britain and America. Britain gained 27 Nobel scientists, the U.S. 47. Germany had dominated science until 1935; after that date, its place was taken by the United States. See: www.nydailynews.com/life-style/nazis-heil-history-nobel-prize-winners-article-1.2762671

Earlier threads may be accessed: Theme table of content