Igor Manko is a photographer in Kharkov, the Ukraine. He has been a member of the National Union of Fine Art Photographers of Ukraine since 1992. He is educated as a linguist and is director of a language school. He has exhibited his photographic work in Kharkov, Kiev, Moscow, Lithuania, the Czech Republic, and Denmark. He has recently exhibited his work on VASA.

“The importance of an artist is to be measured by the quantity of new signs which he has introduced to the language of art.” ( Henri Matisse)

Fine art photography of the city of Kharkiv (Ukraine) since early 1970’s is a story of how a collaborative effort of eight rebellious artists has, over the years, led to the emergence of an art school with a diverse, but distinctive and recognizable visual language.The means of artistic expression, developed by this group and their followers, are still alive for today’s artistic community both in Kharkiv and in the entirety of Ukraine. The history of this school of artistic thought and its aesthetics are described in this essay.

1. Introduction: On socialist realism

The Kharkiv Schoolof Photography’s aesthetic principles emerged within the nonconformist art movement in the USSR as an attempt to break free from the conventional imagery of the Soviet photography dictated by the predominant socialist realism doctrine in art.

Socialist realism, the prescribed aesthetic method of the Soviet art, demanded of the artist “the truthful, historically concrete representation of reality in its revolutionary development… linked with the task of ideological transformation and education” in an attempt to create “an entirely new type of human being.” Socialist realism was officially introduced in 1934 for the purpose of smothering the freedom of artistic expression and suppressing the 1920’s avant-garde movement in the USSR as part of the Communist party’s broader onslaught on all freedoms and the start of political repressions of the Soviet people.

Proclaiming socialist realism as the only true method meant that all other forms of art were denounced as decadent and therefore anti-Communist and were severely censored. A dissident Soviet writer Andrei Sinyavsky in his 1959 essay On Socialist Realism mockingly compared it to a teleological system that would not tolerate the heresy of debate or doubt: “If even once you allow an assumption that the God had unwittingly sinned with Eve, and, jealous of her to Adam, expelled the unblessed spouses into a forced labor camp on Earth, the entire creation concept will go to the dogs, making it impossible to restore the faith in the same form.”

The practical application of socialist realism resulted in oversimplified and quasi-optimistic depiction and glorification of the Soviet reality, “the ‘boy meets girl meets tractor’ genre” 1, in all spheres of artistic endeavor. In photography, socialist realism allowed an artist quite a limited pictorial repertoire. Beautiful Soviet women and handsome Soviet men, engaged in an activity beneficial for the Soviet society (preferably, a factory, a collective farm or a construction site); romantic images of young Soviet people with not more than a hint on eroticism; wise elderly Soviet men with long white beards; happy well-dressed Soviet children on their way to school; landscapes showing the beauty of the Soviet nature – this inventory practically exhausts the list.

Moreover, artistic photography in the USSR was seen as exclusively amateur practice. While artists in other media had their “unions” that allowed them a professional status, art photographers had to be employed elsewhere and engage in art in their leisure time through amateur “photoclubs,” where the above-mentioned “Soviet aesthetics” flourished.

2. Beginning: The Vremya Group

In early 1970’s, the beginning of what later became known as the “period of stagnation”in the Soviet Union history, eight photographers in Kharkiv, Ukraine, joined efforts in fighting the Soviet aesthetic canon and formed an independent (read underground) group of art photography. They called themselves the Vremya Group 2. The nameVremya (время means time in Russian) suggested a move away from traditional imagery towards an innovative form of visual expression.

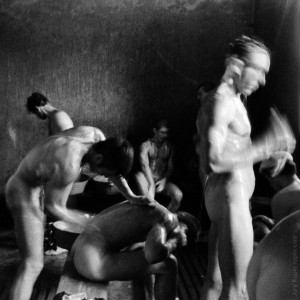

©Yuri Rupin. The Sauna, 1975

The Vremya Group started its fight for artistic freedom by trying to look behind the ideological façade of socialist realism. They pictured food shortage queues, drunks, and whores. They chronicled the hypocrisy of May Day demonstrations and the pomp of Victory Day parades, devastated streets, crumbling down suburbs,and abandoned countryside. They portrayed ugliness, nudity, and lust.

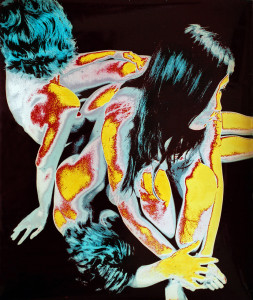

The Red Series, 1978

This kind of artistic activity was far from safe in the USSR. Taking photos of a number of objects and in certain places, like plants, train stations, Communist party buildings, or even bazaars, was prohibited. A person with a camera could be taken in for interrogation and accused of spying. Boris Mikhailov was fired from his job when a KGB search found nude photos in his darkroom. Alexander Suprun used a candid camera concealed in a shopping bag and an ingenious device to operate it to get material for his photomontages. But despite closing of their exhibitions, despite censorship and persecution by all sorts of ideological watchdogs, official art critics to the KGB who would search their darkrooms and apartments, the artists managed to secretly create new art and exhibit it. Their images undermined the Soviet Potemkin villages in art and broke the official taboos. Yevgeniy Pavlov’s The Violin series showing nude young men in a deserted spot produced an effect of an exploding bomb when it was published in Fotografia magazine in Poland in 1973.

The Violin, 1972

But the artists were soon to discover that at least one of the socialist realism dogmas – stating the “inextricable connection” between form and content – was, after all, true, and that the conventional old means of art photography expression were not good enough for the sought-for thematic novelty. Unified by the spirit of independence and rebellion, they developed the “blow theory,” which claimed that shocking the viewer was the only means to produce an aesthetic impact.

Thus began the search for a new visual language in Kharkiv fine art photography.

“Overlays” (or “superimpositions,” or “sandwiches,” as the artists sometimes called them) were probably their – Boris Mikhailov’s, to be precise – first, if somewhat straightforward invention on the way to the new and more complex means of visual language. Two overimposed color slide film frames were either projected on a screen as a slide show or printed on color photopaper. The technique produced a result similar to multiexposure, but allowed clearer detailing and more combinatory possibilities. The images looked formally new, surrealistic, and grotesque and gave room for multiple interpretations.

Fresco, 1973-1974

Color posterizations (Oleg Malyovany’s specialty) are another example of Vremya Group’s experimenting with form. Now achieved with a help of a routine Photoshop filter, in 1970’s they were printed manually and required complicated technical processes and skilled dexterity in making density separations. The effort was rewarded by the freedom of using color and unusual visual effects, creating “unphotographic” reality in a photo.

©Oleg Malyovany.

©Oleg Malyovany.

The Nude Trio, 1972

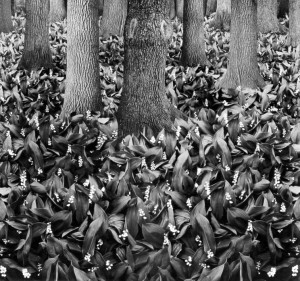

Photomontage was not a new form of expression in photography. Apart from the widely known works of Alexander Rodchenko and his contemporaries in 1920’s, some Lithuanian photographers turned to this technique in 1960’s. Kharkiv artists gave this technique a touch of mastery and artfulness: in the famous Alexander Suprun’s Lilies of the Valley the same flower fragment was used 51 times!

©Alexander Suprun. Springtime in the Forest (Lilies of the Valley), 1975

©Alexander Suprun. Springtime in the Forest (Lilies of the Valley), 1975

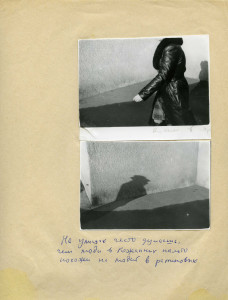

Boris Mikhailov offered a conceptual alternative to sophisticated techniques. He claimed that a high quality glossy image was unable to depict the Soviet reality with its poor life standards (including poor quality of Soviet-made film, paper and chemicals), and suggested the concept of “bad photography for a bad reality.” Instead of full tonal images, he produced small sloppily printed black-and-white photos, often blurred, low contrast, showing film defects or perforation. “Mikhailov introduced ‘bad photography’ as a method to undermine the Soviet compositional canon and the optimistic narrative that the canon served to represent. For Mikhailov, depicting the Soviet reality at the moment of its irreversible and violent break-up, ‘bad photography’ became a tool of aesthetic and social critique” 3 .

©Boris Mikhailov. Unfinished Dissertation, 1984-1985

©Boris Mikhailov. Unfinished Dissertation, 1984-1985

This method was later used in Mikhailov’s famous The Unfinished Dissertation (1984 – 1985, published in 1998) 4, where black-and-white images pasted on the back of somebody else’s lecture notes were accompanied by hand-written comments, autobiographical and philosophical notes, etc. Margarita Tupitsyn wrote in an essay appended to the book, “Mikhailov saw no point in providing an explicit critique of Soviet society, either through mocking it or through unmasking its endless vices. Instead, his goal was to preserve Soviet reality’s sense of totality, but without its layer of systematically sustained external joy.” 5

Some critics believe it was the first example of conceptualism in photography in the USSR: “In fact, only in Kharkov, under the guidance of Boris Mikhailov, did photographic conceptualism actually flourish in Russia,” John P. Jacobs wrote. Until 1990, he maintained, “photographers throughout the USSR, including Moscow, remained hostile to the union of photography with conceptualism.” 6

Similar to “bad photography” being a conceptualist response to a conventional black-and-white photo, hand coloring of black-and-white images responded in kind to the complexity and expensiveness of the color process. It wasn’t a completely new idea. Apart from early 20th century examples of hand colored postcards, studio portraits in the Soviet Union were often handcolored or chemically toned until late 1960’s – early 1970’s, when color photography became more easily available and less technically complicated.

©Victor Kochetov. Banging Down A Spike-nail, 1991

©Victor Kochetov. Banging Down A Spike-nail, 1991

Kharkiv artists used the technique of hand coloring in a variety of ways, from subtle highlighting of a certain detail of the image, as in Anatoly Makiyenko’s cityscapes, to making a photo look like a coloring book page. The latter was characteristic of Victor Kochetov’s brutal and uncompromised approach. He turned his originally realistic black-and-white scenes of shoddy everyday workings of Soviet lifestyle into a work of kitsch, as if taking to its extreme the social realism principle of showing the brighter side of reality in an effort to change it by means of art. Victor Kochetov didn’t formally belong to Vremya but was closely associated with the Vremya artists both socially and aesthetically.

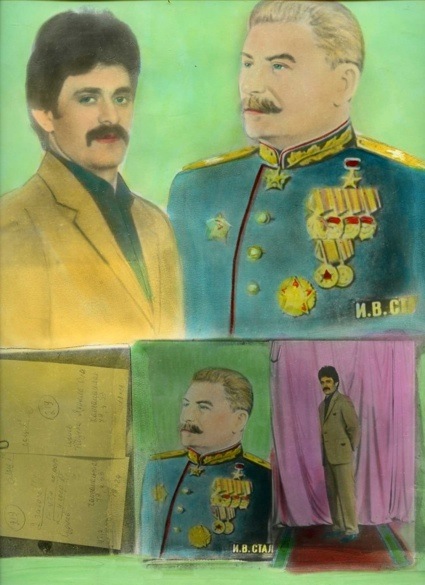

In 1970’s, photographers often earned a living by copying and enlarging people’s family photographs. It was an illegal commercial practice commissioned by people living in rural areas, often in remote parts of the country where color studio photography was either too expensive or simply non-existent. A specifically Soviet product, called a lurik, was a mounted or framed enlarged and retouched hand-colored portrait, postmortem portraits included. Family or passport photos by origin, these desperate examples of true folk art sometimes included instructions: to remove a hat or add more hair, to make a montage coupling two people in one photo of a would-be family, etc. Boris Mikhailov conceptualized this technique in his famous Luriki series, “the first strategic use of found material in contemporary Soviet photography.” 7

©Boris Mikhailov. Luriki, 1985

©Boris Mikhailov. Luriki, 1985

An example of montage instructions: this young man wanted a portrait with Stalin.

3. Continuity

The underground artistic movement of Kharkiv photographers of the 1970’s gave life to a new contemporary aesthetic system in photography which was taken further during the Perestroyka years (1986 – 1991), when ideological barriers were gradually dropped and habitual attempts on censorship lost its dramatic consequences. Later in the 1990’s and 2000’s, despite the economic hardships of the early 1990’s when some artists were forced to change their carreers to be able to earn a living, or even to emigrate, the continuity was preserved.

Since mid-1980’s, younger generations of photographers have been joining in adopting and further developing the new aesthetics, thus postulating the emergence of a school of fine art photography with common goals and shared principles 8.

3.1. Continuity: Documentary photography

While the Vremya Group and its followers were experimenting with montages, overlays,and hand-coloring thus changing the look of traditional photographic images, a collective of younger artists who found a new inspiration in Mikhailov’s black-and-white documentary imagery appeared on the Kharkiv art scene. The Gosprom Group 9, formed in 1986, was named after a world-wide known architectural landmark of the city of Kharkiv. These artists made documentary photographyone of the group’s key aesthetic principles.

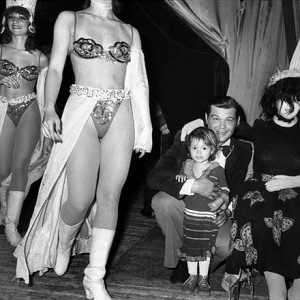

Guennadi Maslov recently published some of his 1980’s images in a photobook Ukrainian Time 10.

©Guennadi Maslov. The Circus, 1984

©Guennadi Maslov. The Circus, 1984

Another photographer from the Gosprom Group, Vladimir Starko chose to work exceptionally with black-and-white film and consciously refused to crop his images. Contemporary audience read Starko’s work as strictly anti-Soviet. His mockingly encyclopedic Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star series showcased the deterioration of the main Soviet symbol. The Window series spoke about the Iron Curtain, which banned the Soviet people access to the rest of the world.

©Vladimir Starko. Prostrated, 1983

©Vladimir Starko. Prostrated, 1983

This approach is still relevant nowadays. Another Gosprom Group artist Misha Pedan elaborated the group’s documentary canon in his recent (2011) Stereo_types project of subtly composed paired images 11.

At about the same time the Shilo Group 12 (formed in 2010) redefined the Gosprom Group method using Lith printing technique. They forcefully placed themselves into the Kharkiv Photography School in a symbolic art gesture of pasting their images over Boris Mikailov’s photos in his Unfinished Dissertation photobook leaving Mikhailov’s text comments intact (The Finished Dissertation project, 2013).

Another recent project that stemmed from the Gosprom Group aesthetics was Kyrill Meshkov’s Chuguyev in Pictures (2012). He furnished black-and-white pictures of his hometown Chuguyev near Kharkiv with absurdist captions revealing the surrealistic atmosphere of its provincial life style.

3.2. Continuity: Photomontage, manual coloring, mixed techniques, etc.

While the Gosprom Group and their followers developed the documentary approach, more sophisticated and complex means of artistic expression (overlays, photomontage, manual coloring and other) – another hallmark of Kharkiv art photography – were pursued in the late 1980’s – 1990’sin the ouevre of both Vremya Group and a younger generations of non-aligned Kharkiv artists.

In early 1990’s, Boris Mikhailov made a significant contribution to his “bad photography” concept. Two large series of chemically toned black-and-white images, At Dusk (1993) and By the Ground (1991), a.k.a. The Blue and The Brown Series, used stains and other defects of color toning as a visual representation of deteriorating life standards of post-Soviet reality.

©Boris Mikhailov. At Dusk, 1993

©Boris Mikhailov. At Dusk, 1993

©Boris Mikhailov. By the Ground, 1991

©Boris Mikhailov. By the Ground, 1991

In 1994, Boris Mikhailov, Sergei Bratkov, and Sergei Solonski joined forces in “The Group of Immediate Reaction,” a Kharkiv School’s attempt on so-called “actual” art, a 1990’s contemporary art movement in the former USSR that claimed the reaction to recent events and issues of current interest to be the focus of art actions. The group’s work was on the borders of art intervention, performance art, and installation.

In late 1990’s, Boris Mikhailov began his famous Case Study project which in the past few years has been exhibited in most prestigious galleries around the world. It has received an international acclaim for demonstrating the miserable condition of a whole stratum of post-Soviet society, those incapable of adapting to the new rules of the game after the USSR collapsed. But the project’s more conceptual angle that escaped critical attention lies in Mikhailov’s choice of homeless hoboes as nude models for the staged photos of the project. Their pathetically inept attempts at posing parody the forged glamor of prevailing visual culture .

Roman Pyatkovka started his engagement in photography in early 1980’sby using familiar Kharkiv school techniques like overlays and hand-coloring. But in 1990, he made The Fantoms of the ‘30-s, a series dedicated to the Great Famine of 1932 – 1933 in the Ukraine, when millions of people were starved to death. It was partly based on found material and partly staged. In both cases Pyatkovka uses multiple reproduction of the original images with hand scratching of the photo.

©Roman Pyatkovka. Phantoms of the ’30th, 1990

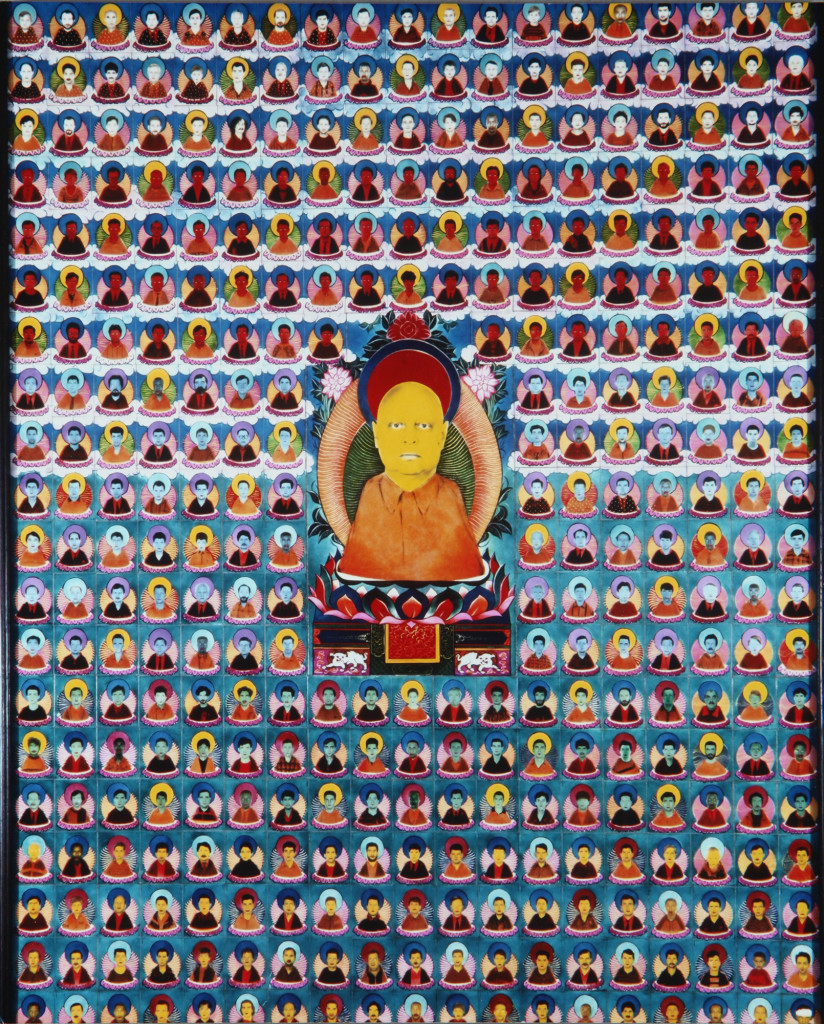

In early 1990’s, Igor Chursin was making decadent staged hand-colored images and renting a commercial photo studio where he earned a living shooting passport photos. A lot of Ukrainians at the time needed passports as, after decades of isolation, they could finally travel abroad. In 1994 Chursin produced his stunning Ukrainian-Mongolian Folk Art collages consisting of hundreds of hand-colored passport photo images.

©Igor Chursin. Ukrainian-Mongolian Folk Art, 1994

Photomontage in 1990’s and 2000’s rejects its past attempts on perspective and spatial fraud in imitating documentary reality.

Sergei Solonsky uses the photomontage technique to create his phantasmagoric images sometimes consisting of the same repetitive fragment. “Corporeal fragmentations in his pictures from the turn of the 1980’s-1990’s started the aesthetic revolution in Ukrainian photography” say Tatiana Pavlova in her 2001 essay. 13

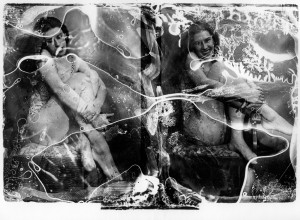

Roman Pyatkovka in his 1995 The Games of Libido series inventeda “negative photomontage” technique, where original black-and-white negatives were glued onto a glass plaque surface and printed immediately while the glue was corroding the film. The resulting images were limited to the issue of 3 to 5 depending on the dexterity of the printer and produced a strikingly unusual multi-layered visual effect.

©Roman Pyatkovka. Games of Libido, 1995

©Roman Pyatkovka. Games of Libido, 1995

The art of photomontage was mastered to perfection in Yevgeniy Pavlov’s oeuvre of the 90’s, where black-and-white and color fragments were combined with manual coloring and scratching, resulting in unique and highly sophisticated-looking images.

©Yevgeniy Pavlov. Untitled, 1994

©Yevgeniy Pavlov. Untitled, 1994

Pavlov transforms dust and scratches on film emulsion, ragged edges of torn-out fragments, and other artifacts into elements of his visual language. In his 1990 – 1994 Total Photography, as well as in some later projects, Pavlov uses all possible techniques available to him (including the use of found material) to illustrate the project concept that any photographic image can be made into a work of art.

In 2011, a Kiev-based artist Yaroslav Solop started his Plastic Mythology project (ongoing) in which he further advances the method. He uses all sources, including Internet graphics, fragments of his own and somebody else’s photos, sometimes hand-colored, which he digitally pastes over his analogue images of naked young people to make ironic illustrations to the ancient myths.

©Yaroslav Solop. Farewell to Hercules, 2011

©Yaroslav Solop. Farewell to Hercules, 2011

Yaroslav Solop claims he has never seen Pavlov’s The Violin or his 1990’s photomontages, but even more evident is the continuity of the Kharkiv school in his work.

Valera Cherkashin, who was briefly associated with Kharkiv photography in late 1970’s– early 1980’s, experimented with pencil drawing over photographic images. Roman Minin in 2000’s uses photographs as a background for his primitivistic color drawings.

Roman Pyatkovka’s Soviet Photo series (2013) is a digital montage of his Soviet period nude photos over page scans of “The Soviet Photo,” once a popular periodical on photography in the USSR. It is the most recent attempt on the overlays technique in Kharkiv photography. It is also an ironical attempt to fulfill a dream of all the artists at the time – to see their work on the prestigious magazine’s pages. The project won the 2013 Sony Photography Award in the Conceptual Photo category.

©Roman Pyatkovka. Soviet Photo, 2013

The purpose of this paper was to research the aesthetics of Kharkiv fine art photography of 1970 – 2010’s as a uniform system of artistic principles, techniques and ideology, its contribution to the visual language of fine art photography, and its implementation in a variety of individual styles and genres. It shows that the aesthetic paradigm of Kharkiv photography continues to nurture the thinking and the work of emerging photographers in Kharkiv and influences other Ukrainian artists.

Since a length of an essay cannot cover the immensity of the phenomena, apologies to the artists superficially or not at all mentioned are hereby offered.

- Sheila Fitzpatrick ‘The Cultural Front: Power and Culture in Revolutionary Russia’, 1992, Cornell University Press, p. 209. ↩

- The Vremya group (early 1970-s – mid-1980-s): Anatoly Makiyenko, Oleg Malyovany, Boris Mikhailov, Yevgeni Pavlov, Yuri Rupin, Alexander Sitnichenko, Alexander Suprun, Guennadi Tubalev. ↩

- Iryna Sandomirskaya ‘The End of la Belle Époque’ (in Misha Pedan, The End of La Belle Époque, 2013, Khimaira förlag). ↩

- Boris Mikhailov. Unfinished Dissertation, 1998, Scalo Publishers, 1st edition ↩

- Margarita Tupitsyn. Photography as a Remedy for Stammering, in Boris Mikhailov. Unfinished Dissertation, 1998, Scalo Publishers, 1st edition, pp. 218 – 220. ↩

- John P. Jacobs. After Raskolnikov: Russian Photography Today, Art Journal, Vol. 53, No. 2 (Summer, 1994), p. 22-27. ↩

- John P. Jacobs, op. cit. ↩

- In 2010 Misha Pedan and Roman Pyatkovka initiated the Ukrainian Photographic Alternative association, bringing together about 100 photographers of mostly 2000-s generation, opposing traditional tastes of the majority. ↩

- The Gosprom group (1986 – early 1990-s): Sergey Bratkov, Igor Manko, Guennadi Maslov (1986 only), Konstantin Melnik, Misha Pedan, Leonid Pesin, Boris Redko, Vladimir Starko. ↩

- Guennadi Maslov. Ukrainian Time, 2013, Hanna House Books ↩

- Misha Pedan. Stereo_typ, 2011, Khimaira förlag. ↩

- The Shilo Group (formed in 2010): Vladislav Krasnoschok, Sergey Lebedinsky, Vadim Trikoz. ↩

- Pavlova T. The Realm of Flora//Imago-2001, -No 12. – P. 46-54 ↩