Return to the Table of Contents

Damiana Gibbons is an Assistant Professor at Appalachian State University in Media Studies in Curriculum and Instruction. She holds a Ph.d in Literacy Studies from the University of Wisconsin-Madison where she was a member of the Games and Learning Society research group. Her research focuses on ethics in youth media production, identity, and media literacy practices with young people. Also, she has created and published on an analytic methodology called multimodal microanalysis to understand the media products young people create.

As a person who grew up in a small, rural town in Wyoming, I have always been interested in how rural places shape the people who live in them. Whether rural people spend all of their energies attempting to flee to larger cities or they spend their time planting their roots to stay in their local communities, rural people are tied to the land and people in their communities that is distinct from those in urban centers. 1. Place matters because rural people often face being stereotyped as being backward or as lacking the social capital to move ahead in life, often seen as moving toward urban centers. 2. Also, there are relationships to the land itself that rest on the idea of sustainability 34 that are fraught with conflict at times, such as the push to save one’s land from coal mining or other resource extraction industries 5, or at other times, are built upon strong desires to remain in one’s place, such as the desire keep family farms in rural areas 6 or to stay in one’s hometown. 3

Therefore, in rural places there exists the idea of rural social space, which is an understanding that acknowledges that defining oneself as rural is cultural as well as geographic and that reflects the interplay of production, people, and place. 8 Within rural social space, a rural person must acknowledge both one’s physical place as well as one’s social place in his or her community. Rural people come to “know one’s place” in their community. 9 In this article, I will expand on this idea of rural social space to discuss how rural people must also “show one’s place” in their media in complex and interesting ways.

Using multimodal microanalysis 10 11, I will explore how people represent particular truths and selves in films depending on where they are situated in place, in particular in rural places. By looking at how rural people engage with complex representations of truth, self, and community in media, such as films, I’m attempting to develop a conceptual understanding about place that sheds light on how one’s position in the world can impact the parameters of what one can consume and produce in terms of media literacy practices in rural areas.

Though there is a belief that representations of oneself is up to an individual alone or that we can display any identity that we’d like both in person and in online spaces, what I have found in past work is that people tell particular kinds of stories of who they are to particular people in particular places 12 10 14, an idea that holds true whether people are posting their media online or whether they are watching it together in film screenings. When it comes to producing media texts, how we make media speaks to who we are as people, the identities we try out and take on and off. Burn (2009) discusses how this is occurring in digital representations when he states that “media genres and technologies allow dramatic reworking of aspects of the world closely related to identity—cultural passions, fashions, play, narratives, of self, family and friends.” 15 What choices people make when creating media can tell us a lot about how they are representing themselves and what they are representing about their world from their own place and time. Therefore, it not only matters who a person is or what media they are consuming or producing, it also matters what is seen as “truth” with those people in that space or place.

This rests on the idea that people cannot create whatever they want, however they want. They must follow the social rules of the place that they are creating from. It matters where a person is when it comes to understanding how truth is determined by a group of people in media production. When it comes to “showing one’s place” in rural filmmaking, this becomes even more of a factor. Rural social space governs the subjectivities available to rural people as they become more (media) literate. Therefore, I will discuss part of a multimodal microanalysis 10 of a film created in a rural area for a rural arts organization, Elizabeth Barret’s (2000) Stranger with a Camera, to illustrate how rural places set up particular ways of being and knowing that set them apart as particular discursive spaces that people navigate when they create and consume in their different literacy practices.

Image © Damiana Gibbons 2013

Multimodal microanalysis is a way to analyze films that is based, in large part, on the idea of the kineikonic mode.

With the kineikonic mode, one traces particular filmic elements—music, action, shot level, written language, speech, movement over time, and the design of social space—as well as how those elements work together. With the kineikonic mode, there is usually one mode that carries the most meaning in a scene, e.g., the image itself tells the story with the music only highlighting the image. This mode is called the “functional load,” and it holds the “stronger weight, or determining function at any given moment.” 17 I have expanded on Burn and Parker’s kineikonic mode to develop multimodal microanalysis, a way to analyze films. 18

Image of Multimodal Transcription © Damiana Gibbons 2013

Stranger with a Camera (2000) is a documentary film directed by Elizabeth Barrett, an Appalshop filmmaker. This documentary explores the context surrounding the murder of a Canadian filmmaker named Hugh O’Connor in the 1960s as he was making a film documentary about everyday Americans, in this case, the people in Appalachia. He was shot and killed by a local, Appalachian man named Hobart Ison. While this is the main topic, the documentary also explores complicated dynamics, especially around representation by community filmmakers and misrepresentation of the local Appalachian people by outsiders. Therefore, the arguments in this film are multiple and complicated. In the documentary, Barrett attempts to wrestle with issues of representation, identity, and truth all with explicit discussions of how being in rural Eastern Kentucky affects all of those themes. I will discuss two of these arguments and how they are constructed through Barrett’s modal choices.

Images from Stranger with a Camera © Elizabeth Barrett 2000

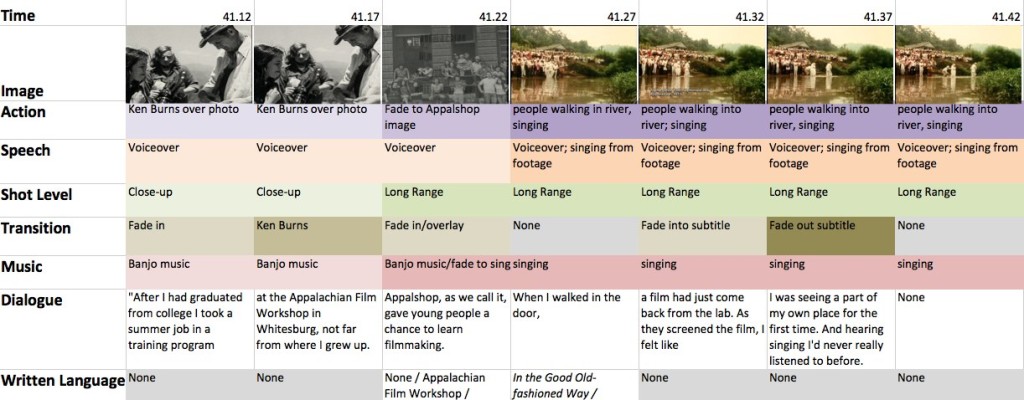

One of Barrett’s arguments is that truth is partial, and media is a double-edged sword in terms of both harming and enlightening in the name of truth. Through multimodal microanalysis, one can see that Barrett is creating a counter-history through the modal choices she is making in the film.

The images show archival video footage. The speech, however, is what is telling the counter history as she combines her own commentary along with voices of others from her community through interviews and voiceovers overlaying the archival video footage. When Barrett does use the speech from the archival videos, it is of Charles Kurault’s 1964 CBS report in which he walks along a dirt road, describing the houses as “shacks of tar paper and pine” and the people as “permanently poor.” She counters his words with her own voiceover in which she questions what the children featured in that documentary must have thought about being portrayed negatively in this way and discusses her own personal history at that time. In the dialogue, the local voices in the commentary discuss how they participated in the media shown as the image and other forms of television footage like it. For instance, a widow of a local lawyer who had written what is considered by the local people to be a canonical book in Appalachia about the region and its people, spoke about how her husband had come to write that book and how she’d helped him with it.

Another key argument Barrett makes is that though her rural place and its people and culture are under attack from those outside, she has a strong connection to place, and through filmmaking, she can both protect her community as well as understand and represent it. In her film, Barrett shows this theme as well when she refers protecting her community as well as representing it throughout the documentary. For instance, in one scene, she describes her time as a youth participant at the rural arts organization. She chooses video footage and audio from another rural produced film, In the Good Old Fashioned Way, but she adds dialogue to the image and sound to show she gained sense of place and of identity:

When I walked in the door, a film had just come back from the lab. As they screened the film, I felt like I was seeing part of my own place for the first time. And, hearing singing I’d never really listened to before. This place I’m from had more of a hold on me than I had realized. These films were showing our place back to me that was completely different than the television programs of CBS and Charles Kurault. Those earlier programs served a purpose, but they weren’t the whole story. 19. (Available from Appalshop, 91 Madison Ave., Whitesburg, KY, 41858).]

She follows this voiceover with a series of images of the rural arts organization films. In speech, dialogue, and image, she is making a space for local filmmakers telling their own stories. Therefore, what we see from Barrett’s use of modal choices, then, is making the argument that others from the outside can and do misrepresent people from her area, but a local filmmaker and local people can voice a counter-history to those depictions through how one creates films in that area.

What sets rural films such as Barrett’s apart from others online or in urban areas is the connection the filmmakers have to their local areas. For Barrett, she shows this by making a compelling argument about truth, representation, and identity at the end of the film. She states:

This is my community. My life is here. As a filmmaker, I have the responsibility to see my community for what it is. To tell the story, no matter how difficult….It is the filmmaker’s job, my job, to tell fairly what I see, to be true to the experiences of both Hugh O’Connor and Hobart Ison, and in the end, to trust that this is enough. 19. (Available from Appalshop, 91 Madison Ave., Whitesburg, KY, 41858).]

With this kind of perspective, Stranger with a Camera is empowering for this type of vision because rural filmmakers tell their stories as their community’s story, and they exhibit that that their responsibility lies in creating their filmmaking in a way that respects both those inside and outside their community. If done in this way, the films are enough.

What makes films, such as Stranger with a Camera, so compelling as examples of rural media literacy is how the rural filmmakers “show their place” in the rural social space depicted in the films. They create complex, rich representations of their places and of their place, both socially and physically. These arguments defy the stereotyping so prevalent about rural areas and provide powerful counter-narratives to mainstream ideas about rural people. In this way, rural filmmaking is a media literacy practice worth fostering as a way to give voice to those often underrepresented or mischaracterized by filmmakers outside those rural areas, e.g., in films such as Deliverance. While it would be interesting to see how place matters to urban filmmakers, this article is a start at making a case for place as a factor in media literacy production, and in this way, this article is making space for analyses of these films in the future.

Return to the Table of Contents

- Donehower, K. (2013). Why not at school? Rural literacies and the continual choice to stay. In B. Green & M. Corbett (Eds.), Rethinking Rural Literacies: Transnational Perspectives (pp. 35–51). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan ↩

- Green, B. (2013). Literacy, rurality, education: A partial mapping. In B. Green & M. Corbett (Eds.), Rethinking Rural Literacies: Transnational Perspectives (pp. 17–34). New York, NY: Palgrave-Macmillan ↩

- Donehower, K. (2013). Why not at school? Rural literacies and the continual choice to stay. In B. Green & M. Corbett (Eds.), Rethinking Rural Literacies: Transnational Perspectives (pp. 35–51). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. ↩

- Donehower, K., Hogg, C., & Schell, E.E. (2012). Reclaiming the rural: Essays on literacy, rhetoric, and pedagogy. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press. ↩

- Howley, C. B., & Howley, A. (2010). Poverty and School Achievement in Rural Communities: A Social-Class Interpretation. In K. A. Schafft & A. Youngblood Jackson (Eds.), Rural Education for the Twenty-First Century: Identity, Place, and Community in a Globalizing World (pp. 34–50). University Place, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press. ↩

- Edmondson, J. (2003). Prairie Town: Redefining rural life in the age of globalization. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc ↩

- Donehower, K. (2013). Why not at school? Rural literacies and the continual choice to stay. In B. Green & M. Corbett (Eds.), Rethinking Rural Literacies: Transnational Perspectives (pp. 35–51). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. ↩

- Reid, J.A., Cooper, M., Hastings, W., Lock, G., & White, S. (2010). Regenerating rural social space: Teacher education for regional-rural sustainability. Australian Journal of Education, 54(3): 262-276. ↩

- Gibbons, D. (Under review). Rural media literacy: Rural youth filmmaking as a media literacy practice. Manuscript prepared for The Journal of Research in Rural Education. ↩

- Gibbons, D. (2010). Tracing the paths of moving artifacts in youth media production. English Teaching: Practice and Critique, 9(1): 8-21. ↩

- Curwood, J.S. & Gibbons, D. (2010). “Just like I have felt”: Multimodal counternarratives in youth-produced digital media. International Journal of Learning and Media, 2(1), 59-77. ↩

- Gibbons, D. (2012). Developing an ethics of youth media production using media literacy, identity, & modality. Journal of Media Literacy Education, 4(3): 256-265 ↩

- Gibbons, D. (2010). Tracing the paths of moving artifacts in youth media production. English Teaching: Practice and Critique, 9(1): 8-21. ↩

- Gibbons, D., Drift, T., & Drift, D. (2011). Whose story is it? Being Native and American: Crossing borders, hyphenated selves.” International Perspectives on Youth Media: Cultures of Production & Education. Ed. Fisherkeller, JoEllen. New York: Peter Lang Publishers, Inc. 172-191. ↩

- Burn, A. (2009). Making new media: Creative production and digital literacies. New York, NY: Peter Lang Publishing. ↩

- Gibbons, D. (2010). Tracing the paths of moving artifacts in youth media production. English Teaching: Practice and Critique, 9(1): 8-21. ↩

- Burn, A., & Parker, D. (2003). Analysing Media Texts. Continuum International Publishing Group. ↩

- Curwood, J.S. & Gibbons, D. (2010). “Just like I have felt”: Multimodal counternarratives in youth-produced digital media. International Journal of Learning and Media, 2(1), 59-77. ↩

- Barrett, E. (Director/Producer). (2000). Stranger with a Camera. [Motion Picture ↩

- Barrett, E. (Director/Producer). (2000). Stranger with a Camera. [Motion Picture ↩