Theme Table of Content

VJIC Table of Content

Essay 8

Photography and the Holocaust: Then & Now

AFTERMATH: The Nuremberg Trials

© Robert Hirsch 2023

VASA Journal on Images and Culture (VJIC),

Theme Editor and Writer

www.lightresearch.net

“The history of mankind is the history of crimes.

Recognize that there is evil in the world and be

prepared to take action.”

Simon Wiesenthal[i]

This essay examines the role that photo-based imagery played in the immediate aftermath of Liberation by means of The Nuremberg Trials. Owing to the enormous scope of people affected by the German atrocities and genocide, select examples embody the infinite.

Additional information about specific images can be found at the end of this essay (Image Notes). Images have been minimally adjusted to facilitate online viewing, but have not been overtly edited from their source.

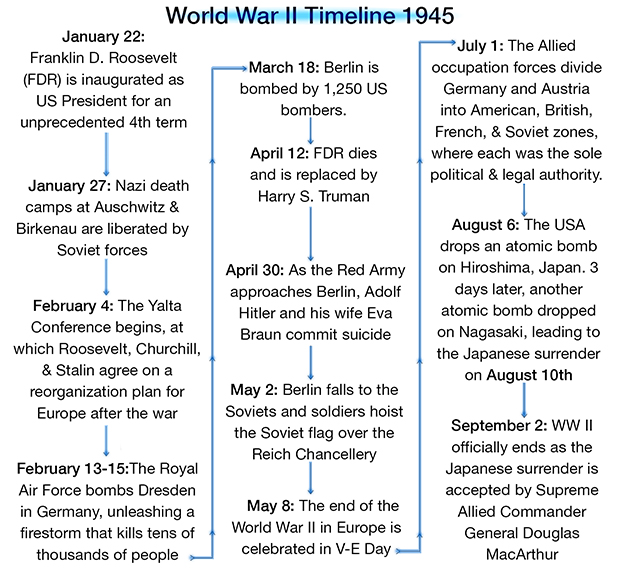

8.00 World War II, 1945 Timeline

8.01 Henri Cartier-Bresson. Gestapo Informer Recognized by a Woman She Had Denounced, Deportation Camp, Dessau, Germany, 1945. Dimensions variable. Gelatin silver print. Magnum Photo.

The Holocaust did not end in 1945 with the liberation of Europe. After fighting their way into Nazi-occupied territory, Allied and Soviet forces discovered and liberated concentration camps, freeing more than two million Europeans, including 250,000 Jewish Holocaust survivors.[ii] However, it was apparent that the loose alliance of the Allies and the Soviets would collapse as their economic and political systems were incompatible and in competition. The Allies were immediately concerned with how to govern, rehabilitate, and to bring some form of justice to the defeated Axis powers in Europe and Japan as well as forming a postwar alliance against Communism. Therefore, Jewish concerns took a back seat even though life for many European Jews was a crime scene within a massive graveyard, often with no place to call a protected home as their entire world had been completely destroyed.

Postwar Nuremberg Trials

8.02 Unknown photographer. Dachau Liberation, Entomologisches Institut der Waffen SS Camp, Germany, 1945. Dimensions variable. Gelatin silver print. Yad Vashem Archives Jerusalem, Israel.

The Allies and Soviets were confronted with what to do with the 8.5 million members of National Socialist German Workers’ Party (Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei) and their millions of collaborators who participated in robbing, torturing, and murdering two out of every three European Jews, wiping out entire centuries-old communities.[iii] The Nazis killed so many Jews that the global Jewish population is still demographically lower today than it was in 1939.

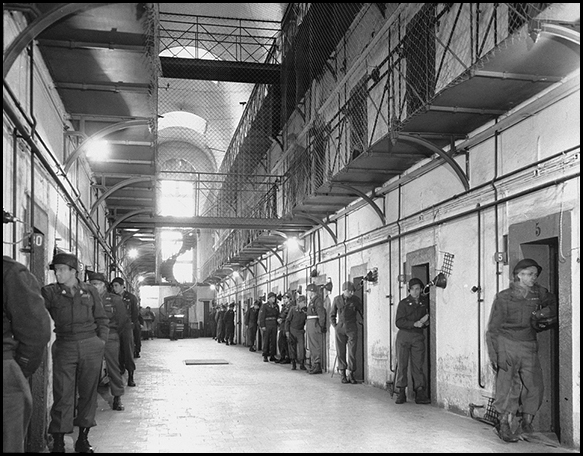

To address the issue of justice, international, domestic, and military courts conducted trials of tens of thousands of accused war criminals. The most well-known of the war crimes trials is that of 22 leading German officials before the International Military Tribunal (IMT) in Nuremberg Germany. This trial began on November 20, 1945. The IMT delivered its verdict on October 1, 1946, convicting 19 of the defendants and acquitting three. Of those convicted, 12 were sentenced to death, including Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, Hans Frank, Alfred Rosenberg, and Julius Streicher. The IMT sentenced three defendants to life imprisonment and four to prison terms ranging from ten to 20 years.[iv] In addition to the Nuremberg IMT, the Allied powers established the International Military Tribunal for the Far East in Tokyo in 1946, which tried leading Japanese officials. Holland set up a special court where more than 65,000 accused collaborators stood trial that stripped some of certain civil rights, sent some to prison, and condemned others to death.[v]

8.03 Unknown photographer. Germans burying the corpses of inmates under the supervision of American soldiers, Schwarzheide, Germany, 1945. Dimensions variable. Gelatin silver print.

8.04 Unknown photographer. The main cell block in the Nuremberg prison, Nuremberg, [Bavaria] Germany, November 24, 1945. Dimensions variable. Gelatin silver print. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, Maryland.

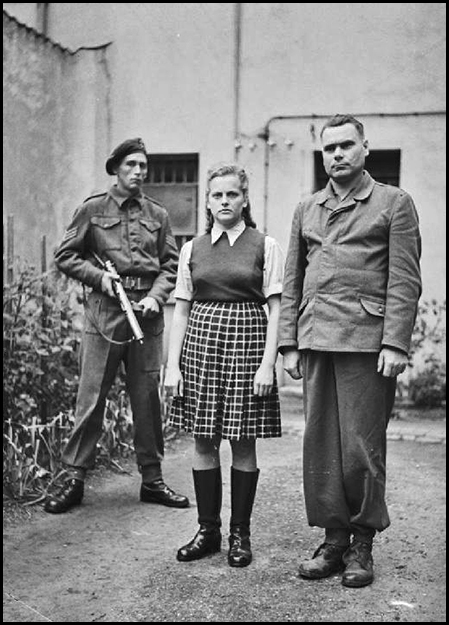

8.05 Sergeant Silverside and Lieutenant A. Turner, No 5 Army Film & Photographic Unit. Irma Grese and former SS Hauptsturmführer Josef Kramer in prison, in Celle Germany, August 8, 1945. Dimensions variable. Gelatin silver print. Imperial War Museums, UK.

8.06 Charles Alexander. The defendants dock at the International Military Tribunal trial of war criminals, Nuremberg, [Bavaria] Germany., January 1, 1946 – October 1, 1946. Dimensions variable. Gelatin silver print. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC.

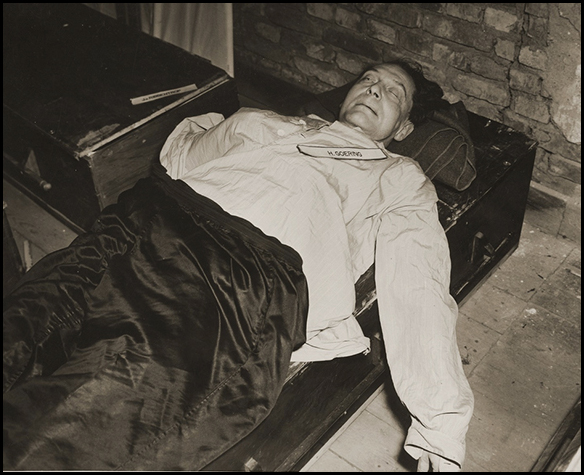

8.07 Edward F. McLaughlin. The body of Hermann Goering after he committed suicide in prison following the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg, Nuremberg, [Bavaria] Germany, October 16, 1946. Dimensions variable. Gelatin silver print. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC.

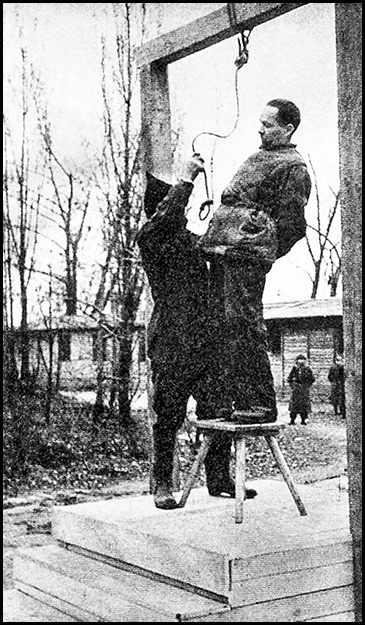

8.08 Stanisław Dąbrowiecki. Rudolf Hoess on the gallows, immediately before his execution, April 16, 1947. Dimensions variable. Gelatin silver print. Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum.

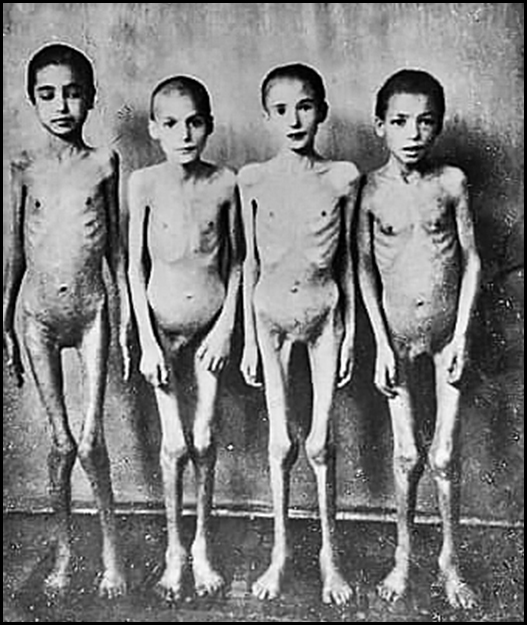

8.09 Unknown photographer. Children at a German Nazi concentration camp subjected to pseudo-medical experiments. Dimensions variable. Gelatin silver print. Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum.

Evidence of a Disaster

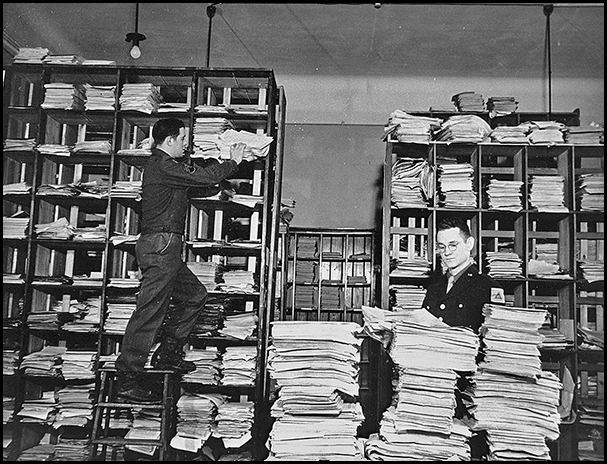

The prosecutors set out to prove Nazi Germany’s crimes through the Germans’ own words and testimony. For example, Eugen Stähle, a doctor and politician who implemented the Nazi murders of over 200,000 people with physical, mental and psychological disabilities stated: “The fifth commandment: Thou shalt not kill, is no commandment of God but a Jewish invention.”[viii] The foundation of their case was based on thousands of such German documents the Allies seized. Most of the witnesses called to testify had been members of the Nazi Party, SS, or German state or military.

8.10 Charles Alexander. American army staffers organize stacks of German documents that were collected by war crimes investigators as evidence for the International Military Tribunal trial of war criminals at Nuremberg, Nuremberg, [Bavaria] Germany, November 20, 1945 – October 1, 1946. Dimensions variable. Gelatin silver print. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD.

8.11 Sergeant H. Oakes, No 5 Army Film & Photographic Unit. SS women camp guards are paraded for work in clearing the dead, April 4, 1945. Dimensions variable. Gelatin silver print. Imperial War Museums, UK.

The original caption sheet read: “S.S. women are also made to work. These women are the equivalent of the men for brutality.”

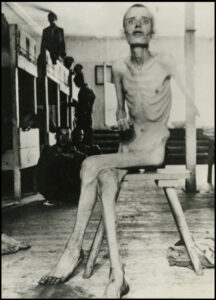

The authenticity of these photo-based images was based on their direct indexical relationship to the time of their making; thus they are themselves a history of a disaster. This was re-enforced because these images were captured as on film, which in pre-digital times were considered by the general public to be permanent, physical records of outer reality. Thus, like an archaeological find, these images delivered realistic, primary evidence of the past in the present that people would accept as accurate. Although the profusion of Holocaust photographs can be numbing, these images offer a powerful defensive time machine against amnesia. In classic documentary approach, they can act as potent instruments of imaginative reconstruction, even when they offer an illusion of a presence when the reality is that of a vast absence.

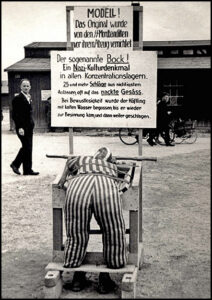

8.12 Unknown photographer. Model of the torture device nicknamed “Billy the goat” exhibited in the camp (probably Bergen-Belsen, Germany). Dimensions variable. Gelatin silver print. Yad Vashem Archives, Jerusalem, Israel.

Unlike Holocaust deniers, the Nazi defendants did not deny the accuracy of the documentary evidence they themselves produced, demonstrating how the making of photographs mirror their makers. Although they maintained no personal responsibility for the crimes, under the IMT’s charter, the defendants could not assert innocence on the grounds that they were following orders. People forget words, but remember pictures, as they can make an indelible impression in a viewer’s mind. Thus, the top Nazis were hoisted by their own petards.[x] The degrading way they pictured Jews was yet another form of war, that of lives not worth living. With bitter irony, these obscene images redeemed themselves as eyewitnesses to their depravities.

This demonstrates how photographs are in flux, their purpose and meanings can be reinvented and used for contrasting purposes depending on what the maker wants to represent, their context, and how the audiences decide to interpret them. Collectively, the meaning of the Shoah photographs can be pursued either in a straight line, like a canal, or they can be looked at in a more expressionistic fashion, like a meandering brook, letting one’s imagination float down-stream as in CEPA Gallery’s (Buffalo, New York) upcoming photo-based project that has grown out of these essays (see Afterword). The latter posits that if the goal of these photographs is to make the experience of life more — more thoughtful, more intimate, more immediate, more painful, more surprising, and even more beautiful — then this is the route. This is one way that the generations of makers haunted by the Holocaust can continue the telling in a manner that rehumanizes and reinvigorates this history.

What none of the photographic or written evidence can answer is how, in the blink of an eye, humans can turn from church going, family orientated neighbors to mass-murderers and back again. Indirectly, these photographs raise a fundamental question about human nature: Is there free will or are we prisoners of our circumstances, environment and/or heredity? Can we act without the constraint of necessity or fate at one’s own discretion or are all our choices caused by forces and influences over which we have no meaningful control?

A memorable example can be read in Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov (1879-1880). The character Ivan (aka Vanya), whose dictum “if there is no God, everything is lawful,” dreams that the Grand Inquisitor arrests the risen Christ. The Grand Inquisitor does this to sustain happiness and the security that comes from not having to choose good over evil, arguing that the power of choice does not benefit the church’s authority, and that moral freedom is too demanding a burden for most people to manage. We would be correct in perceiving Lucifer’s self-satisfaction in the inquisitors unscrupulous positions, which re-enforces his overarching power to command others without being questioned and grants his underlings the alibi that they were just following orders from an almighty source. For all the shouting we now hear about liberty, those who abuse, threaten, and lie about people who are different from them and decree which books are wicked and must be banned and/or burned, seem terrified of allowing their fellow human beings the right to choose virtue on their own while providing cover for those who carry out dastardly bidding.

This aspect of personal choice and responsibility also reveals how a shared history does not equate with shared memories and assessments of data, which are flexible, fragmented, and shapeshifting based on personal history. Regardless of motive, no survivors were called as witnesses, once again denying Jews a voice in the proceedings that enormously affected them. This must have been frustrating, as Jews did not want only to have history imposed upon them but wanted to possess it, including its ethical and political weight and responsibilities.

The German people’s actions, and lack of actions, following their defeat expressed more self-pity than any moral sense of wrongdoing. Reporting on the Nuremberg Trials for the Jerusalem Post (then the Palestine Post), social historian George Lichtheim concluded that the Nazi movement did not represent just mob mentality. Rather, it had dominated German universities before it triumphed over German society. Thus, it’s irrationality and reactionary romanticism and worship of power was promoted by leading German intellectuals like philosopher Martin Heidegger who joined the Nazi party in 1933. Lichtheim also asserted that it was a corresponding myth that most Germans felt regret for their crimes, stating. “In prosaic fact, most of them are sorry, only for themselves.”[xi]

8.13 Captain Carter. German prisoners of war held in an American camp watch a film about German concentration camps, Buchenwald, April 16, 1945. Dimensions variable. Gelatin silver print. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD.

In the Western zones of post-war Germany, less than 5 percent of the cases heard resulted in a verdict of highly incriminated, incriminated, or less incriminated. More than 95 percent of those investigated were either deemed nominal party members, exonerated, or simply amnestied outright.

Postwar Germans “wallowed” in their own suffering. They perceived themselves as having been “abused” and “duped” by Hitler and devoured by war. In an “extraordinary feat of repression” the Holocaust had to be literally “unspeakable” and “unsayable” for Germans unable to face up to their own guilt. However “infuriating” this “intolerable insolence” may have been, Harald Jähner, former editor of The Berlin Times, concluded that it was a “necessary prerequisite” for the democratization of Germany. It opened the way not for the continuation of National Socialism, but rather for the successful integration of ex-Nazis and a new start. German democratization had “nothing to do with historical justice.”[xii]

The footage that was shown in figure 8.13 came from a U.S. newsreel that was seen by millions and millions of people in an effort to make a case that jarring images can have a deep emotional saturation that is capable of shattering the pseudoscientific Aryan master race delusions (Herrenrasse). This forced process was part of the Allied policy of postwar denazification that brought Germans face-to-face with the worst deeds of the Third Reich — that seeing can convey the meaning or essence of a subject more effectively than a language based description. Images became a vital component in the Allied attempt to purge Germany of the remnants of Nazi rule and rebuild its civil society, infrastructure, and economy. The visual program also included compulsory visits to nearby concentration camps along with posters showing dead bodies of concentration camp prisoners displayed in public places. Think of it as a different way of defining persistence of vision[xiii] – that such images, not one would not want to display in their living room, could remain in the minds of viewers, encouraging them to shake off the status quo and assist Germany into becoming democracy. Bear in mind, these images were more disturbing in their day, before we were visually assaulted with ghoulish cruelties on the nightly news.

Reparations

Beginning in the 1960s, Germany began to “come to grips with the past” (for which the Germans invented the term Vergangenheitsbewältigung). However differently Jähner and other historians portray various factors in Germany’s democratization, they are in agreement that the deferral, often permanently, of a historical and judicial reckoning with the Nazi past was an important element in this process.

It should be noted that between 1945 and 2018, the German government paid approximately $86.8 billion in restitution and compensation to Holocaust victims and their heirs.[xiv] Additionally, Germany will pay $1.2 billion, including emergency aid for Holocaust survivors in Ukraine remembrance education.[xv] Finally, Germany agreed, for the first time, to specifically fund Holocaust education — with 10 million euros allotted for 2022, 25 million euros for 2023, 30 million euros for 2024 and 35 million euros for 2025.[xvi] Even so, plundered Jewish assets that targeted the cultural identity of Jews are still in the possession of official and private hands and remain in the process of being litigated—plus all the world’s wealth can never replace what was lose.[xvii]

Conclusion

Once again, we can observe that often the only thing capable of diminishing humanity’s endless ability to hunker down in a state of denial is indisputable visual evidence. When these ferocious, acts were orchestrated on a massive institutional scale, the Allies utilized harrowing images of the German’s barbaric acts in an attempt to shatter their collective delusions. When all else fails, tell it to the eye. In such instances, the photographic record could act as society’s consciousness, reminding viewers that equal rights and justice are necessary for all in order to have an open and healthy society.

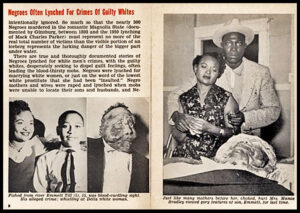

At the time when such images were rarely published, this was considered an effective method to reach large segments of the public (during the war, the U.S. had a policy of not publishing photographs of dead American soldiers). A classic example of a photograph affecting the general public’s call for social justice was the publishing of the mutilated body of Emmett Till, a Black 14-year-old from Chicago who was kidnapped while visiting relatives in Mississippi. He was horribly tortured, and viciously murdered by racist white men for allegedly flirting with a white woman. Emmett’s mother decided to present this nauseating situation by conducting a public funeral and having photographs of his open casket published in Jet, a leading Black magazine. The unpardonable violence these photographs conveyed, combined with the failure of the authorities to bring the perpetrators to justice, are widely acknowledged as a key turning point the U.S. civil rights movement of the 1950s.

8.14 David Jackson. The mutilated body of Emmett Till and his distraught mother, 1955. Dimensions variable. Gelatin silver print. Jet magazine.

In today’s digital world, with its abundance of extremely gratuitous violent images, deep fakes, AI produced pictures, often designed to sow doubt through disinformation, plus endless choices for people to get information, the public’s belief in trustworthy images has evaporated. The result has diminished the ability of any pictorial works to have a broad social influence.

Regrettably, many humans concoct facts that support their beliefs regardless of legitimate documentation. That said, the analog, mechanical nature of the Holocaust photographs, often possessing an anonymous, incidental, snapshot quality, provide an efficient way to express complex ideas. In prosaic terms, they can act as “lint screens” that collect the images in the brain that keep circulating, giving them added intellectual and psychological depth.

Collectively, Shoah images now can serve an expanded societal role by reminding us that what happened in Germany (genocide)[xviii] can, does, and has happened elsewhere and in other times. We see examples of contemporary authoritarian leaders and states targeting groups and individuals that resist their tyrannical ideology. What this indicates is that sadist human beings continue to love making war and gleefully enjoy oppressing others, even down to looting their family snapshots while bystanders passively looked on. This is why, if one teaches historical antisemitism, it is imperative to teach contemporary antisemitism and the tenets of Jewish culture and values, which then rehumanizes those who were dehumanized.

After liberation, my grandmother and I returned home to find that everything was gone. Our family photos, prayer books, even the gilded book I won in school, had been looted. I have been able to recover a few photos of my family from before the Holocaust, but they are all I have. And I’m fortunate. Many survivors only have memories of their loved ones.[xix]

Tribute

8.15 Rose-Helene. Holocaust survivor and a volunteer at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Email, April 16, 2023.

What the Shoah photographs make abundantly clear is that those who are different from the majority need a safe harbor. In this case, the European Jews had nowhere to go. For these outsiders the immediate lesson of the Holocaust was the absolute need for a country of their own, which would make something out of their trauma, honor the dead, and give future generations agency to act upon the world because hate never takes a holiday.

To be continued: Essay 9 – “Displaced Persons Camps and the Pre-Israel State”

Afterword

Photography and the Holocaust: Then & Now

From January through May 2024 CEPA Gallery, Buffalo, New York, USA (www.cepagallery.org) will present a comprehensive exhibition, publication, and community project that investigates the many roles Holocaust (Shoah) photo-based imagery can shape cultural narratives and re-examine history with an emphasis on prejudice and transgenerational trauma. The project will assess photography’s fluctuating role in documenting, interpreting, and understanding the Holocaust, reflecting how past affects the present and the future.

In addition to historic photographs, the large-scale contemporary component will feature an international array of contemporary artists whose practice utilizes historic photo-documents, archival materials, and new imagery to investigate notions of photographic truth, as it relates to personal post-memory effects when creating visual messaging based on historical events. A 100-page catalog will feature essays by the curator and experts in the field as well as maker’s statements and examples of their work.

Intentional outreach and coordinating activities relevant to people of diverse age, social, ethnic, and cultural identity will enable Photography and the Holocaust to create a context for community forums to wrestle with difficult conversations that explore the rise of worldwide antisemitism, nationalism, racism, and tribalism, emphasizing that staying silent is to side with the oppressor.

This multi-part project is curated and produced by the author.

Acknowledgements

Research assistance and project management by Ruby Merritt.

Special thanks to Gail Nicholson for copy editing.

Feedback and suggestions are welcome.

This series of essays is supported by the following organizations and individuals:

VASA: Roberto Muffoletto, Director

CEPA Gallery, Buffalo, NY USA: Claire Legget, Executive Director

[i] Simon Wiesenthal (1908-2005) was a Jewish Austrian Holocaust survivor, Nazi hunter, and writer who lost some 89 members of his family in the Shoah. He became the unofficial spokesperson for the millions of murdered Jews by bringing 1,100 Nazi war criminals to justice, with little assistance from an essentially indifferent world. See: Simon Wiesenthal Center at www.wiesenthal.com

[ii] What had been happening in these camps was not news. The U.S. Government learned about the systematic killing of Jews almost as soon as it began by the Germans in the Soviet Union during 1941. Throughout the war the Allies prioritized defeating Nazism, not saving Jews.

[iii] The Germans rehearsed for the Holocaust during the Herero and Nama War (1904-1908), systematically imprisoning and murdering tens of thousands in what is now Namibi. It is considered the first genocide of the twentieth century. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herero_and_Namaqua_genocide

[iv] For details see: The Holocaust Encyclopedia, “Postwar Trials,” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/war-crimes-trials

[v] Nina Siegal, “Dutch to Make Public the Files on Accused Nazi Collaborators,” The New York Times, April 25, 2023, www.nytimes.com/2023/04/25/arts/dutch-files-accused-nazi-collaborators.html

[vi] Ralf Beste, et al, “The Role Ex-Nazis Played in Early West Germany,” Spiegel International, March 6, 2012, www.spiegel.de/international/germany/from-dictatorship-to-democracy-the-role-ex-nazis-played-in-early-west-germany-a-810207.html

[vii] See: “Postwar Trails https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/war-crimes-trials, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC.

[viii] Eugen Stähle on December 4, 1940 to a Württemberg Evangelical Higher Church Council, quoted by Ernst Klee, Euthanasia in the Nazi state: The destruction of life unworthy of living, Frankfurt: Fisher paperback, 2004, 16.

[ix] Holocaust Encyclopedia, “We will show you their own films,” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/we-will-show-you-their-own-films-film-at-the-nuremberg-trial

[x] Petards were small, unreliable medieval bombs made of gunpower that often prematurely exploded, hurting the bomber instead of the intended target.

[xi] Benjamin Balint, “George Lichtheim’s Marxmanship,” Jewish Review of Books, Winter 2023, 23.

[xii] See review of Harald Jähner’s Aftermath, Christopher R. Browning, “Adenauer’s Bargain,” The New York Review, December 22, 2022, www.nybooks.com/articles/2022/12/22/adenauers-bargain-aftermath-harald-jahner/

[xiii] Persistence of vision is an optical illusion in which the human eye continues to briefly see an image after it has disappeared from view. The impression of an object seen by the human eye remains on the retina for 1/16th of a second. If we see another object before this time, the impressions of the two images merge to give us a sense of continuity and movement, which is the basis for motion pictures.

[xiv] See: U.S. Department of State, “The JUST Act Report: Germany,” www.state.gov/reports/just-act-report-to-congress/germany/

[xv] Erika Solomon, “Germany Offers One of the Largest Holocaust Reparations Packages, and a Special Fund for Ukrainians,” The New York Times, September 15, 2022, www.nytimes.com/2022/09/15/world/europe/germany-holocaust-reparations-ukraine.html?searchResultPosition=1

[xvi] Kirsten Grieshaber, “Germany marks 70 years of compensating Holocaust survivors,” Associated Press News, September 15, 2022, https://apnews.com/article/holocaust-survivor-compensation-fund-germany-0d35aa1cba7756d1b9b6008e9d7841b7

[xvii] See: U.S. Department of State, “The JUST Act Report: Germany,” www.state.gov/reports/just-act-report-to-congress/germany/

[xviii] The term, genocide, was coined by Raphael Lemkin in 1944. Genocide has been defined by Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (CPPCG), or the Genocide Convention as: “any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial, or religious group, as such: killing members of the group; causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group; deliberately inflicting on the groups conditions of life, calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part; imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group; [and] forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.” List of genocides: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_genocides

[xix] Rose-Helene (last name withheld to protect privacy). Holocaust survivor and a volunteer at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Email, April 16, 2023.