Return to theme table of content

Return to VJIC table of content

Thread #4

Jewish & Partisan Photographic Perspectives, Part 2

© Robert Hirsch 2022

www.lightresearch.net

VASA Journal on Images and Culture (VJIC), Theme Editor and Writer

God has no children whose rights may be safely trampled on.[i]

Frederick Douglass, 1854

This essay explores the photographic work of Faye Schulman, Francisco Boix, and the Sonderkommando whose photographs speak to resistance to the Holocaust. Henryk Ross will be covered in a separate essay. Through the photographs of a few we see many.

Note: Additional information about the images can be found at the end of this essay. Images have been minimally adjusted to facilitate online viewing, but have not been overtly edited from their source.

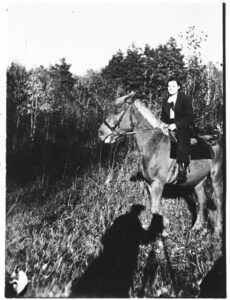

4.1 Faye Schulman. Faigel Lazebnik poses on horseback, 1944. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC, courtesy of Faye Schulman.

Faigel “Faye” Lazebnik Schulman: Resistance

Official Nazi propaganda, which has dominated how most people viewed the Holocaust, depicted Jews as disease carrying vermin in need of extermination.

4.2 Faye Schulman. Members of the Shish detachment of the Molotov partisan brigade pose in the forest with their weapons, 1942-1944.

What is still not widely known is that some 30,000 Eastern and Western European Jews, many of them teens, fought back as Jewish partisans and were responsible for procuring food and medicine; tending to wounded soldiers; derailing German trains; injuring German soldiers; sabotaging German communications, supply lines, and the products they were forced to make; punishing collaborators; forging documents; and freeing Jews from ghettos. Resistance by Jews was complicated because, in addition to the dangers, they were subjected to communal responsibility and reprisals from both the Nazis and antisemitic Parisians. Even so, Jews commanded about 200 partisan groups.

Faigel “Faye” Lazebnik Schulman, one of the few known WWII Jewish partisan photographers[ii], grew up in Lenin, a town on Poland’s eastern border, where Jews were prohibited from holding public positions. She learned photography from her brother Moishe, the town photographer, and took over his photography business when she was sixteen. In her home town, the Nazis carried out a mass shooting that killed about 1,850 local Jews, including most of her family. She was spared as the Nazis deemed her ‘useful’ and enslaved her to make photographs, including headshots of Nazi officials and portraits of their mistresses. During one portrait session a Gestapo commander told her: “It better be good, or else you’ll be kaput.”[iii]

4.3 Faye Schulman. Shulman with Three Comrades, 1944. Jewish Partisan Education Foundation.

One day, she developed a photograph depicting a mass grave of the Lenin Jews who had been machine-gunned by Lithuanian collaborators and the local police, and recognized the bodies of her parents, sisters, and younger brother. She secretly made a copy photograph of the atrocity, which spurred her to join the resistance movement.

4.4 Faye Schulman. Shulman (second row right) with Shish detachment field operating table, 1942-1944. US Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC, courtesy of Belarusian State Museum of the History of the Great Patriotic War.

During a partisan raid, she fled to the forests and convinced the commander to let her join the Molotava Brigade, a partisan group made mostly of escaped Soviet Red Army prisoners of war. At only 19 years old, she was the only Jewish woman amongst a group of non-Jewish men. She had to keep her Judaism a secret because of the intense antisemitism in the group, which had killed hundreds of “unaffiliated” Jews who had escaped into the forest.[iv] As her brother-in-law was a doctor, a veterinarian trained her as a nurse, although she had no actual medical experience. She served in this position from September 1942 to July 1944, assisting with surgeries on gurneys made of branches. Once, after numbing a fellow fighter with vodka, she sniped off his wounded finger bone with her teeth. She slept with a gun she used in guerilla combat missions, including a raid on her hometown, during which she recovered her previously buried photographic equipment.

4.5 Faye Schulman. Partisan Burials, 1944. Jewish Partisan Education Foundation

Over the next two years, Schulman made over one hundred photographs, developing the Compur camera’s medium format negatives under blankets at night and using printing out paper to make “sun prints” without a darkroom.[v] This was remarkable considering she was both fighting for her life in the woods and making do with found photographic equipment and supplies.[vi] When she went on missions, she buried the camera and tripod to keep it secure. Once again, group cooperation was necessary to make these unusual photographs, which required her guidance and knowledge.

After the liberation, she married Morris Schulman, a partisan commander. They spent three years living in a displaced-persons camp in Germany where she had to abandon most of her photographic work, able only to save her favorite photographs. The couple continued their resistance, joining an underground organization supporting the rebirth of Israel, the first Jewish state in 2,000 years, by smuggling European Jews and weapons into British-controlled Palestine. In 1948, she, her husband, and their infant emigrated to Canada.

“I want people to know there was resistance, Jewish

people didn’t go like sheep to the slaughter … I was a

photographer. I have pictures. I have proof.”[vii]

Schulman’s courageous photographic collection delivers a first-person account about what it takes to confront authoritarian ultranationalism with its regimentation of society and brutal suppression of opposition. They exemplify the will to resist and persevere against the overwhelming Nazi tyranny machine, designed to break down people’s resolve and turn them into silent, obeying accomplices. Each image is a portrait of personal choice in the face of death. As an anthology, her photographs and autobiography counter the Nazi narrative that forges Jewish identity around meek victimhood. They are remembrances that alienated and marginalized Jews did not ask for special treatment, but only wanted the opportunity to uphold the same standards of achievement, conduct, and ethics as everyone else.

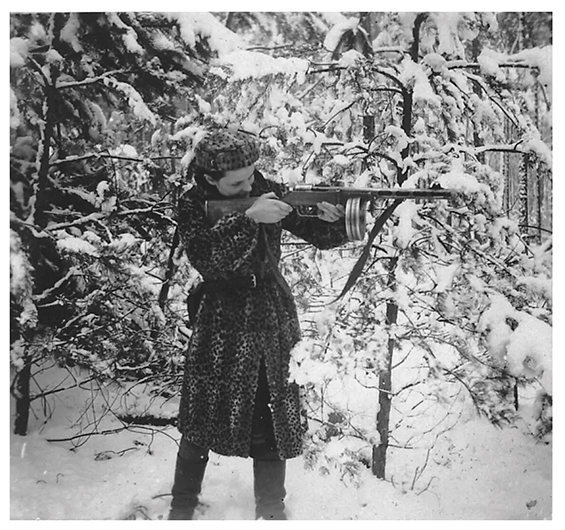

4.6 Faye Schulman. Practicing with a Rifle, 1943. Jewish Partisan Education Foundation.

4.7 Faye Schulman. Schulman with her Detachment, 1942. Jewish Partisan Education Foundation.

Francisco Boix Campo: Prisoner Resistance

4.8 Francesco Boix Collection. Francesco Boix Mauthausen registration photographs, 1940. Arxiu Nacional de Catalunya. Departament de Cultura.

In 1940, at age 20, Francesco Boix Campo,[viii] a Republican veteran and photographer of the Spanish Civil War, was imprisoned in the Mauthausen concentration camp. The Germans sent an estimated 7,000 Spaniards to Mauthausen, where about 5,000 Spanish captives were worked to death under slave-labor conditions in quarries nicknamed Knochenmühle (the bone grinder). It was also the location of the Schutzstaffel’s (SS) official photographic identification service. Here they photographed all new prisoners and made ethnographic photographs supporting sham Nazi racial theories. Additionally, SS photographers documented visits by high-ranking Nazis, public executions, and “souvenirs” of their depravity. Copies were distributed to the high-ranking SS officer Karl Schutz as well as to the SS headquarters in Berlin, Linz, Oranienburg, and Vienna. Many of the surviving photographs were likely made by SS Hauptscharfuehrer Paul Ricken, a trained photographer who worked with a 35mm Leica.

Boix, who could speak German, was first assigned to work as a translator, but because of his photographic skills, he was assigned to the camp’s photo laboratory. Before Boix’s arrival, other photographic assistants were clandestinely stashing copies of incriminating images. This collective operation was expanded after Boix arrived, and by 1944, Boix was copying all of SS images that he could and hiding them, with the assistance of the camp’s communist underground resistance movement. The group was able to smuggle these negatives out of Mauthausen, sewn into the clothes of the teenage prisoners who were laboring in jobs outside the camp. The boys delivered them to Anna Pointner, an Austrian anti-Nazi sympathizer, who hid them behind a rock in her garden wall until the end of the war.

When the Americans liberated Mauthausen on May 5, 1945, Boix and his fellow prisoners had preserved more than 3,000 images of Nazi crimes. This turned out to be a vital act of resistance—few incriminating camp photographs survived as the retreating Nazis’ destroyed such proof. These photographs were used as evidence in the Nuremberg war crimes trials in 1946.[ix]

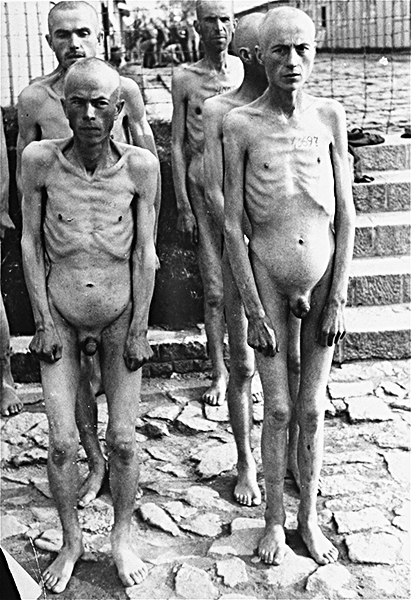

4.9 Paul Ricken/Francesco Boix Collection. Naked Soviet POWs, 1944

In the witness box, while the secretly amassed images were projected onto a screen above him, the French prosecutor asked Boix: “What is this picture?” Boix testified: “A Jew whose nationality I do not know. He was put in a barrel of water until he could not stand it any longer. He was beaten to the point of death and then given 10 minutes in which to hang himself.”[x]

4.10 Paul Ricken/Francesco Boix Collection. The frozen body of a Jewish prisoner who was beaten to death by the SS lies in the snow, 1943. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD.

Boix’s photographs , depicting Germans sending people to the gas chambers, pushing men off a 70-foot-high cliff into the quarry, and killing for amusement and pleasure, were proof of what he had observed.

4.11 Paul Ricken/Francesco Boix Collection. Prisoners (lower left) at forced labor in the Wiener Graben quarry at the Mauthausen concentration camp, 1942. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD.

Additional photographs confirmed Heinrich Himmler’s presence, one of the most powerful men in Nazi Germany and a principal architect of the Holocaust, in the camp’s death quarry. Additionally, Boix identified Albert Speer, Hitler’s architect and minister of armaments, in a photograph taken at the camp. These stealthily-stashed photographs bolstered the court’s verdict: a death sentence for Himmler and 20 years in prison for Speer.

4.12 Paul Ricken/Francesco Boix Collection. Commandant Franz Ziereis points out something to Heinrich Himmler and other SS officials while viewing the quarry during an inspection tour of the Mauthausen concentration camp, 1941. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC, courtesy of Archiv der KZ-Gedenkstaette Mauthausen

Boix died in 1951, at age 30, probably as a result of the health issues contracted at Mauthausen.

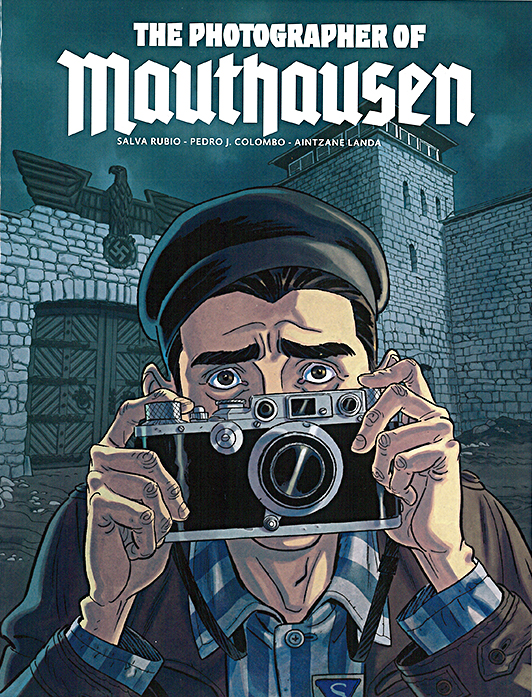

4.13 Salva Rubio (writer), Pedro J. Colmbo (artist), and Aintzane Landa (colorist). The Photographer of Mauthausen, 2020 (English edition). Dead Reckoning/Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD.

The Auschwitz Sonderkommando Quartet

The Sonderkommandos (special command unit) were groups of young, relatively healthy, male Jewish prisoners forced to perform a variety of duties in the gas chambers and crematoria of the Nazi camp system. They were coerced into leading other Jews into the gas chambers, and then to untangled bodies, clean the chamber, and dispose of the corpses. They shaved the victim’s hair, extracted gold teeth, and removed clothes and valuables, which were turned over to the ever-vigilant SS, before taking them to the

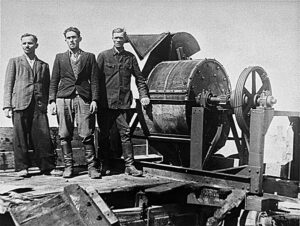

4.14 Unknown photographer. Bone-crushing machine used by Sonderkommando 1005 to grind the bones of victims after their bodies were burned in the Janowska camp, 1944. US Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC.

crematoria. Afterwards, their remains were ground to dust in a bone crushing machine and mixed with the ashes. When too much ash accumulated, the SS would order them to throw the human remains into a nearby river. If they refused, they would be tossed in the gas chambers or shot on the spot by an SS guard. Eventually, the majority were gassed as they became sick or weak to comply, or simply because the Nazis did not want any witnesses to their moral inversion.

Many judge the Sonderkommandos as traitorous kapos.[xi] This position was articulated by German-Jewish political philosopher, Hannah Arendt, who was forced to leave Germany in 1933 and eventually immigrated to the United States in 1941. Arendt took the position that everything in life is a choice – to do it or not to do it, stating: “there was no possibility of resistance, but there existed the possibility of doing nothing. And in order to do nothing, one did not need to be a saint, one needed only to say: ‘I am just a simple Jew, and I have no desire to play any other role.’[xii]” In The Drowned and the Saved (1986), writer Primo Levi placed them in gray zone comprising those who were morally compromised in some degree because of their collaboration with the Germans. Others observe that their behavior is entirely human as most of us will do anything necessary to live another day.

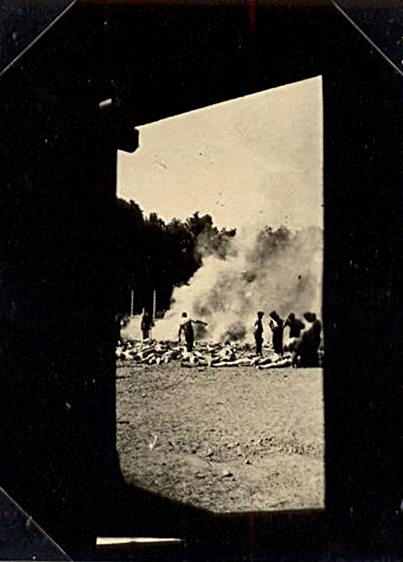

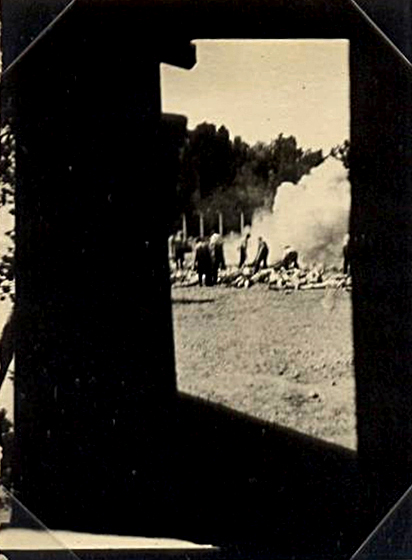

What we also see is that, even under these desperate dualistic conditions, there was resistance. Despite the ban on photography and the ever-present threat of execution, these Sonderkommandos used a smuggled camera and film as a weapon to record their living horror show as an act of defiance as they feared nobody would believe what was happening.[xiii]

It is believed that a Jewish, Greek prisoner, Alberto Errara, with the assistance of others in his unit, made four photographs depicting their gruesome work near the gas chambers at Auschwitz-Birkenau, which were smuggled out by the Polish resistance. We do know it was a clandestine, collective activity that required the trust and cooperation of a group of the walking dead who found themselves in an inconceivable situation and yet organized the will to disobey and practice the act of photographing what they saw.[xiv] This is what makes these four photographs uniquely different from other Holocaust images: they are not remembrances, but immediate, atrocious moments in Jewish history that these men were living through without reprieve.[xv] Secretively making these photographs helped provide these men with purpose enough to bear their torture. Directly after the Shoah, the Austrian philosopher, psychiatrist, and Holocaust survivor, Viktor Frankl slightly recast a Friedrich Nietzsche Maxim in his Man’s Search for Meaning (1946), writing: “He who has a why to live for can bear with almost any how.”[xvi]

4.15 The Open Door; William Henry Fox Talbot (English, 1800 – 1877); Lacock, Wiltshire, England; late April 1844; Salted paper print from a Calotype negative; 14.9 x 16.8 cm (5 7/8 x 6 5/8 in.); 84.XO.968.167

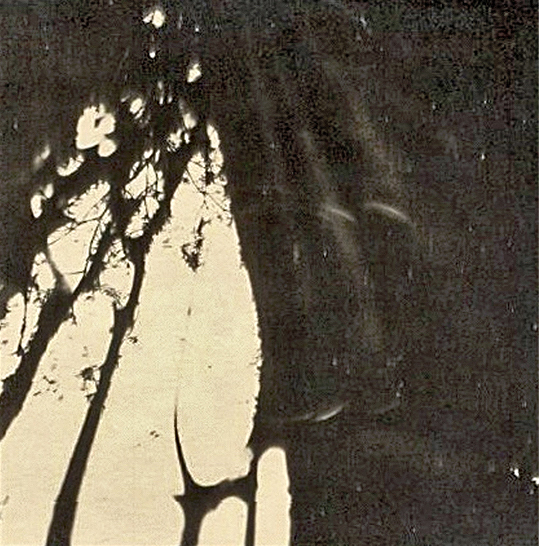

The first reaction people have when they see this series of ambiguously perplexing photographs is: What is happening here? The only classic aesthetic device in this sequence is the black doorway that acts as a framing device, harkening back to William Henry Fox Talbot’s The Open Door (1844). Even so, it was likely circumstantial as these photographs were quickly made in secret from a hiding place. They do not possess the characteristics of what most people consider to be good photographs or deliver what people expect to see. In fact, they are the opposite of what people want to see. There is nothing uplifting in these photographs. These are pictures that made people look away. If anything, they are portraits of entropy, confirming a decline into nothingness. This in turn reiterates how difficult-to-interpret images can seemingly tell us everything—even if by themselves, they tell us nothing at all.

However, once the hasty, indexical, barbarous context of the burning naked bodies is understood, angular, blurry confusion turns to visceral, stomach-churning nausea as we glimpse hell on earth. There are no moments of grace in these bleak images, only the smoke of Hell.

The gas chambers are the Holocaust, but there are no photographs of what happened in there, only results. This quartet of photographs pulls back the curtain, and within this Dantesque inferno one gets a grim glimpse, not an allegory or a metaphor, but a direct transmission into a reign of terror. In this sense, it is fitting that these fragmented compositions, with their missing pieces, represent the actual absence of Jews and the smokey partials of their lost culture.

These death slaves knew they were condemned and utilized a camera to send a message into the future proclaiming:

Look

We were here

Look at what we saw

Look at what we did

Look what they made us do

Look at what they did to us…

In Survival in Auschwitz (1995) Primo Levi recalled how, driven by thirst, he breaks off an icicle only to have it snatched away by a guard. “Why?” Levi asks. The guard relies: “Hier ist kein warum” (Here there is no why).[xvii]

People thought Auschwitz was unimaginable, yet everything was possible in Auschwitz, including this photographic quartet of endurance against the smokey ashes of erasure. These death-row prisoners were exemplars of documentary photography through their accurate, straightforward representations of events, people, places, and objects. Their images of profound desolation attest that deafening silence in the face of the Holocaust was not an acceptable response and how the actions of a few can affect the future.

About the Sonderkommando Quartet Photographs

The black frame of the gas chamber’s doorway or window is visible in photographs 280 and 281. In photograph 281, a fragment of photograph 282 can be seen on the left, which means that the order in which the images were taken contradicts the numbering of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum: photograph 282 of the women undressing in the birch woods precede the images of the cremation pits.[xviii] The original negatives and prints have been lost. The reproductions are from prints made in the 1950s. The numbering was assigned by the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum. Photographic details are provided to help clarify what was taking place.

4.16 Alberto Errera/Auschwitz Sonderkommandos. No. 280, framed by the gas chamber’s doorway or window, 1944. Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, Oświęcim, Poland.

4.17 Alberto Errera/Auschwitz Sonderkommandos. No. 280, framed by the gas chamber’s doorway or window (detail) 1944. Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, Oświęcim, Poland.

4.18 Alberto Errera/Auschwitz Sonderkommandos. No, 281, framed by the gas chamber’s doorway or window, 1944. Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, Oświęcim, Poland.

4.19 Alberto Errera/Auschwitz Sonderkommandos. No. 282, Naked women being taken to the gas chamber, 1944. Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, Oświęcim, Poland.

4.20 Alberto Errera/Auschwitz Sonderkommandos. No. 282, Naked women being taken to the gas chamber (detail), 1944. Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, Oświęcim, Poland.

4.21 Alberto Errera/Auschwitz Sonderkommandos. No. 283: Trees near the gas chamber, taken shortly after No. 282, 1944. Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, Oświęcim, Poland.

Conclusion

The Holocaust was the first genocide photographed from multiple points of view: by the killers, the by-standers, and even the victims; photography validated the undeniability of the Shoah. Previously, very few people were familiar with photographs of Jewish life before and during the Shoah. This was because most were made under dreadful circumstances by private individuals with no official status who lacked the means to circulate them. It was not until decades after the Holocaust that these and other photo-based materials came to wider public attention. This was compounded by the fact that the early written accounts by survivors, such as Elie Wiesel, were written in Yiddish. The first abridged English edition of Wiesel’s Night was not published until 1960 and intentionally took a different tone, appealing to a universal gentile audience—playing down Jewish anger and suffering by emphasizing the Christian belief of Turning the Other Cheek.

However, these photographs are not a means to an end or valued in themselves, but rather helpmates in achieving an end in itself. This makes them the opposite of the fine art photography gallery model, our current benchmark of worth, which is based on monetary branding, collectability, and status.

Holocaust photographs did serve as crucial evidence in convicting perpetrators in the momentous post-World War II war crime trials. However, beyond titillating voyeurism and belated handwringing, what is the social value of these photographs today? Photographs are not ethical codes and cannot sustain the weight of moral reckoning on an international scale. Juries are not tasked with deciding overarching issues of fairness, but rather with applying a specific set of laws to specific testimony. Holocaust trials were not capable of repairing social damage, answering larger issues, or fulfilling notions of justice.

That said, these photographs can be transmitters of mindfulness, proof of historic atrocities that help ignite self-awareness and make us ask why one does what one does. Still, with endless Holocaust denial, inversion, and revisionism,[xix] these eyewitness photographs have not been able to change the conditions that lead to the Shoah and subsequent genocides[xx] nor, as a collection, have they played a large role in how the Holocaust is visualized or understood.

What we confront is the limits of such personally made photographs: people often lack the strength or the will to recognize evil within themselves or to connect historic evil with present societal or political conditions. The horror in those photographs remains other, alien, unrelated to themselves or their world. However, the existence of these photographs and the desire for them to be shown to generation after generation, allows a space for hope, for the possibility that some will make the connection between past and present and engage in the progressive work necessary to protect humanity from its most vile instincts.

4.22 Emanuel Leutze. Washington Crossing Delaware River, 1851. 149 x 255 inches. Oil on canvas. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

What makes this collection of Holocaust photographs unique is they do not commemorate a single individual. There is no heroic image of George Washington crossing the Delaware River. What we have is a cooperative effort to preserve, endure, and survive. Another aspect that makes these Holocaust photographs distinct from typical World War II photographs is that they are first-hand testimonies to the violent decrees against which they were produced. These photographs are capable of communicating much more than they depict, acting as gateways to other paths of inquiry. As in the Rabbinic tradition,[xxi] these photographs succeed in asking the moral questions: What leads ordinary people to commit evil? Do leaders and followers who demonstrated no mercy deserve forgiveness? What does it take to be a good person and how can one live a principled, empathetic life? Humans often prefer rewriting history rather than learning from it, as we see in the continual disowning of the ancient Jewish connections to Jerusalem.[xxii]Such de-Judaization of history is another form of antisemitism, reminding us that not every narrative is legitimate.

4.23 The Golem, How He Came into the World (film still), 1920. Directed by Paul Wegener/Carl Boese. Written by Paul Wegener/Henrik Galeen. German Film Museum (Deutsches Filminstitut), Frankfurt, Germany.

As enlightenment does not appear on the horizon, nor is there a Golem coming to the rescue, another unmistakable message these photographs deliver is that the world does not consider Jews to be like everyone else, even those who have assimilated. Time has taught Jews that submerging their identity is usually more beneficial than advertising their saga. This is because, when push comes to shove, the world still considers them to be perpetual “Jews.” Whether it was out of hate, fear, envy, personal gain, and/or indifference, Yad Vashem’s The Righteous Among the Nations database (The World Holocaust Remembrance Center in Jerusalem) only recognizes 27,920 individuals (0.05% of Europe’s 1939 population) as actively helping Jews survive the Shoah.[xxiii] One noticeable photographic exception was the Leica Freedom Train (circa 1938—1939), in which the Leitz family smuggled hundreds of Jewish employees and colleagues out of Nazi Germany to Leitz sales offices in Britain, France, Hong Kong, and the United States.[xxiv]

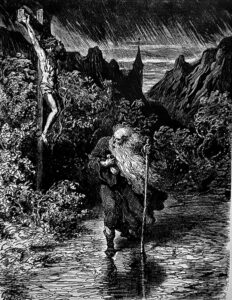

4.24 Gustave Doré. The Legend of the Wandering Jew, A Series of Twelve Designs, with explanatory introduction, 1856. 21-11/16 x 15-1/4 inches. Wood engraving on paper.

What these photographs make clear is that antisemitism is dangerous and ubiquitous and does not require a physical place to manifest itself. Rather, it is a state-of-mind based on emotional, illusory conspiracy beliefs that blame others for one’s problems. Even in the best of times, stereotypical “Wandering Jews”[xxv] have found themselves in the untenable situation of being treated as “guests” in a stranger’s house who have to obey rules imposed upon them and were subject to displacement at the homeowner’s discretion. This is made evident in the sardonic joke attributed to the Russian British political thinker Sir Isaiah Berlin: “An antisemite is someone who hates Jews more than is absolutely necessary.” If photography can be a form of testimony, then what these photographs adjacently reveal is that Jews are the elemental Other and the hatred directed at Jews is the result of the phobia of those who are different from the mainstream, and why Jews needed and continue to require a permanent safe harbor.[xxvi]

If the cry of “Never Again”[xxvii] is to be realized then the Jewish state of Israel[xxviii] is a necessity as place of sanctuary to avoid future catastrophes. To think otherwise is to acknowledge that these photographs were made in vain. As Tom Lehrer sang in “Everybody Hates the Jews” (1965), the only thing that has changed in regard to antisemtism is that social media has made it more acceptable and easier to express such abhorrence…[xxix]

Oh, the Protestants hate the Catholics

And the Catholics hate the Protestants

And the Hindus hate the Muslims

And everybody hates the Jews[xxx]

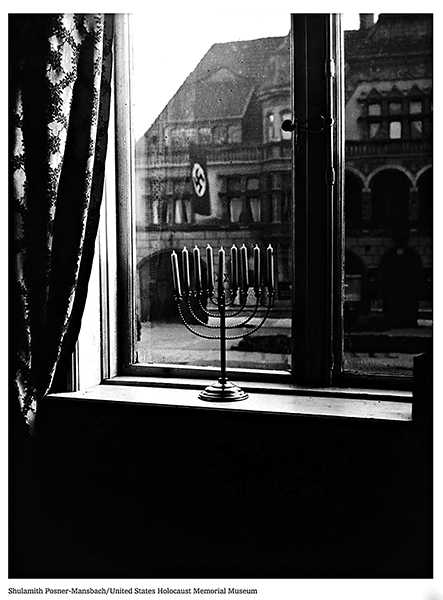

4.25 Rachel Posner. Menorah With Nazi Flag, circa 1932. Shulamith Posner-Mansbach/United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC.

Afterward

This ongoing project is flexible and subject to revision as it progresses.

Feedback and suggestions are welcome.

Research assistance by Ruby Merritt

Special thanks to Lisa Murray-Roselli for her copy-editing expertise.

This theme is supported by the following organizations and individuals:

VASA, Vienna Austria: Roberto Muffoletto, Director

CEPA Gallery, Buffalo, NY USA: Véronique Côté, Executive Director & Chief Curator

Galicia Jewish Museum, Kraków, Poland: Tomasz Strug, Deputy Director and Chief Curator

Holocaust Resource Center of Buffalo, Buffalo, NY USA: Elizabeth Schram, Director

Jewish Community Center of Greater Buffalo, Buffalo, NY USA: Katie Wzontek, Cultural Arts Director

Footnotes:

[i] “The Claims of the Negro Ethnologically Considered,” July 14, 1854 in Howard Brotz (editor), African-American Social & Political Thought 1950 – 1920, (Routledge: Oxford and New York, 1992). https://books.google.com/books?id=ICMxDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT295&lpg=PT295&dq=God+has+no+children+whose+rights+may+be+safely+trampled+on.&source=bl&ots=2iiss5Q9wQ&sig=ACfU3U3Sgkax6PHPgYjivmzSW6Tu4vDe5w&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwimx6nC05P1AhWJk4kEHTBQA6UQ6AF6BAgnEAM#v=onepage&q=God%20has%20no%20children%20whose%20rights%20may%20be%20safely%20trampled%20on.&f=false

[ii] For more on Jewish Partisans, including video interviews with Schulman, visit the Jewish Partisan Educational Foundation at: www.jewishpartisans.org

[iii] Sam Roberts, “Faye Schulman Dies: Fought Nazis With a Rifle and a Camera,” The New York Times, May 28, 2021, www.nytimes.com/2021/05/28/world/europe/faye-schulman-dead.html

[iv] Faye Schulman, A Partisans Memoir: Woman of the Holocaust (Toronto: Second Story Press, 1995), 104.

[v] Printing out paper (P.O.P.) are gelatin-chloride papers, which are contact-printed with a negative using the sun (UV light source) to make a visible image without development, after which the paper is fixed and washed.

[vi] Along with rationing of household staples such as meat, dairy, and coffee, the Allies and Axis powers marshalled their national resources for war production, making photographic equipment and supplies hard to procure. See: Donald C. Holmes, “Wartime Photographic Activities and Records Resulting Therefrom,” Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

http://meridian.allenpress.com/american-archivist/article-pdf/10/3/287/2742261/aarc_10_3_1q687m1553317472.pdf

[vii] Faye Schulman Biography at: www.jewishpartisans.org/partisans/faye-schulman

[viii] In this Spanish name, the first or paternal surname is Boix and the second or maternal family name is Campo.

[ix] It was essential that the Allied International Military Tribunal (IMT) carried trials out under international law and the laws of war as the entire German political, military, judicial, and economic leadership was run or polluted by Nazis who continued to be “recycled” for decades to come. See: Yannick Pasquet, “German justice system was contaminated by Nazis for decades after WWII,” The Times of Israel, November 18, 2021, www.timesofisrael.com/german-justice-system-contaminated-by-nazis-in-post-wwii-years-researchers-find/?utm_source=The+Daily+Edition&utm_campaign=daily-edition-2021-11-19&utm_medium=email

[x] Matthew Blackman, “The Photographer Whose Work Signed Himmler’s Death Warrant,” OZY, December 15, 2019, www.ozy.com/true-and-stories/the-photographer-whose-work-signed-himmlers-death-warrant/246996/

[xi] A kapo was a Nazi concentration camp functionary who was assigned by the SS guards to supervise forced labor and/or carry out administrative tasks in return for special privileges. Many were common criminals and were brutal to fellow inmates, but others were selected because of their special skills and training. This form of “prisoner self-administration,” minimized costs by allowing camps to function with fewer SS personnel, which made them hated by the other enslaved inmates.

[xii] “Eichmann in Jerusalem: An Exchange of Letters Between Gershom Scholem and Hannah Arendt,” Encounter 22 (January 1964): 51 – 56, reprinted in Hannah Arendt: The Jew as Pariah: Jewish Identity and Politics in the Modern Age, Ron H. Feldman, ed., (New York: Grove Press, 1978), 240 – 251; 248.

[xiii] The United States and Great Britain had evidence about the murderous concentration camps as early as the summer of 1942 and did nothing about it, eventually even refusing to bomb the railroad tracks into Auschwitz. See: Mitchell Bard, “Auschwitz Bombing Controversy: Could The Allies Have Bombed Auschwitz-Birkenau?” www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/could-the-allies-have-bombed-auschwitz-birkenau

[xiv] Dan Stone, “The Sonderkommando Photographs,” Jewish Social Studies, Vol. 7, No. 3, Indiana University Press, 2001, pp. 131-148, www.jstor.org/stable/4467613

[xv] For a detailed philosophical reflection of these photographs see: Georges Didi-Huberman, Shane B. Lillis (translator), Images in Spite of All: Four Photographs from Auschwitz, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008).

[xvi] In Twilight of the Idols, or, How to Philosophize with a Hammer/Maxims and Arrows (1889) Friedrich Nietzsche wrote: “If we have our own ‘why’ of life we shall get along with almost any ‘how.’”

[xvii] Primo Levi, Stuart Joseph Woolf (translator), Survival in Auschwitz, (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995), pp. 29. First published as If This Is a Man (1947).

[xviii] See: Jean-Claude Pressac, Auschwitz: Technique and Operation of the Gas Chambers, (New York: Beate Klarsfeld Foundation, 1989), 424.

[xix] “Denial of the Holocaust and the genocide in Auschwitz,” http://auschwitz.org/en/history/holocaust-denial/ and “Holocaust Denial and Distortion,” www.ushmm.org/antisemitism/holocaust-denial-and-distortion

[xx] See: “The Anti-Defamation League Global 100 study measuring public attitudes and opinions toward Jews in over 100 countries” https://global100.adl.org/map

[xxi] Judaism teaches one to ask questions, to question the unquestionable and challenge the conventional, in the belief that intelligence is God’s greatest gift to humanity. The Torah contains no word meaning “to obey.” Instead, the Torah uses the verb shema, untranslatable into English as it means: (1) to listen, (2) to hear, (3) to understand, (4) to internalize, and (5) to respond. The Shema (Hear O’ Israel, the Lord is our God, the Lord is One) is the centerpiece of Judaism’s daily morning and evening prayer services. See: www.myjewishlearning.com/article/the-shema/

[xxii] Tovah Lazaroff, “129 nations ignore Jewish ties to Temple Mount, call it solely Muslim,” The Jerusalem Post, December 2, 2021, www.jpost.com/international/129-nations-ignore-jewish-ties-to-temple-mount-call-it-solely-muslim-687592?_ga=2.129006990.369480656.1636311589-1969581575.1579377799&utm_source=ActiveCampaign&utm_medium=email&utm_content=New+X-ray+machine+could+allow+fast+diagnosis+of+COVID+pneumonia&utm_campaign=December+2%2C+2021+Night&vgo_ee=pe0QfTCmmHdt%2Fu78LjdvmuVBBEpOL%2FVH1LgWNl%2BjZec%3D

The UN shows contempt for Judaism and Christianity by adopting a resolution that makes no mention of the name Temple Mount, where the first and second Jewish temples once stood. Since 2015, the UN’s General Assembly has adopted 112 condemnatory resolutions targeting Israel, more than any other country, according to a tally by UN Watch. The second most targeted country was Russia, with 13 resolutions. See: www.algemeiner.com/2021/12/02/watchdog-condemns-united-nations-assault-on-israel-after-raft-of-one-sided-resolutions-adopted/

[xxiii] See: www.yadvashem.org/righteous.html

[xxiv] Matt Williams, “Leica Freedom Train: How the Leitz Family Saved Jews in the Holocaust,” PetaPixel, November 17, 2021, https://petapixel.com/2021/11/17/leica-freedom-train-how-the-leitz-family-saved-jews-in-the-holocaust/

[xxv] The legend of the immortal Wandering Jew began in 13th century Europe as one who could randomly scavenge but never securely reap. In this allegorical fairytale, the Jew who taunted Jesus on the way to his Crucifixion was cursed to perpetually walk the Earth as endless punishment until the Second Coming. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wandering_Jew

[xxvi] Rich Tenorio, “20 years before the Holocaust, pogroms killed 100,000 Jews – then were forgotten,” The Times of Israel, December 21, 2021, www.timesofisrael.com/20-years-before-the-holocaust-pogroms-killed-100000-jews-then-were-forgotten/

[xxvii] The phrase was coined by the liberated prisoners at Buchenwald to express their anti-fascist stance. It may have adopted from a 1927 poem by Yitzhak Lamdan: “Never again shall Masada fall!” Masada was the site of the 73/74 CE Roman siege of the rebellious Jewish fortress overlooking the Red Sea. When Roman troops breached the fortress, they saw the defiant defenders had set fire to all the buildings and committed mass suicide and/or killed each other, 960 men, women, and children rather than submit to Roman domination.

[xxviii] When examining the world’s religious majorities by country, Israel is the only country that has a Jewish majority: about 75%. Worldwide: Christianity – 2.38 billion; Islam – 1.91 billion; Hinduism – 1.16 billion; Buddhism – 507 million; Folk Religions – 430 million; Other Religions – 61 million; Judaism – 14.6 million; Unaffiliated – 1.19 billion. See: “Religion By Country 2021” https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/religion-by-country

[xxix] Bari Weiss, “Everybody Hates the Jews,” Common Sense, September 20, 2021, https://bariweiss.substack.com/p/everybody-hates-the-jews

[xxx] Tom Lehrer, “National Brotherhood Week,” 1965. Full version of the song at: https://genius.com/8494897

[xxxi] The Mandate for Palestine was a League of Nations mandate for British administration of the territories of Palestine and Transjordan, both of which had been conceded by the Ottoman Empire following the end of World War I in 1918. When the Roman’s conquered Israel and destroyed the Second Temple (70CE) they changed the name to Palestine, after the Jews’ ancient enemy, the Philistines.

Image References:

4.1 Faye Schulman

4.1 Faye Schulman. Faigel Lazebnik poses on horseback, 1944. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC, courtesy of Faye Schulman.

Caption: Lazebnik set up the camera and tripod (the shadow is visible in the foreground) and had a friend shoot the photograph.

4.2 Faye Schulman.

4.2 Faye Schulman. Members of the Shish detachment of the Molotov partisan brigade pose in the forest with their weapons, 1942-1944. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC, courtesy of Belarusian State Museum of the History of the Great Patriotic War.

4.3 Faye Schulman.

4.3 Faye Schulman. Shulman with Three Comrades, 1944. Jewish Partisan Education Foundation.

Caption: Two weeks after the mass killing in Lenin, during a partisan attack, Shulman escaped and joined the partisans of the Molotova Brigade. “These boys escaped the Nazi-occupied half of Poland and came to Lenin in 1939, when we first met…. I was happy to meet three Jewish boys together. In my brigade, I couldn’t even say I was Jewish…. So, when I saw boys I knew, I was very happy not to hide anything.” Faye Schulman, A Partisan’s Memoir: Woman of the Holocaust (Toronto: Second Story Press, 1995), p. 139.

4.4 Faye Schulman. Shulman

4.4 Faye Schulman. Shulman (second row right) with Shish detachment field operating table, 1942-1944. US Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC, courtesy of Belarusian State Museum of the History of the Great Patriotic War.

4.5 Faye Schulman. Partisan Burials, 1944. Jewish Partisan Education Foundation

4.5 Faye Schulman. Partisan Burials, 1944. Jewish Partisan Education Foundation

Caption: Formal burials of partisans were rare. Schulman took this photograph to show the first time her detachment’s casualties were buried in caskets…. “These are two Jews and two gentiles, all four buried in one grave together…. They fought together against the same enemy, so they are buried together.” Faye Schulman, A Partisan’s Memoir: Woman of the Holocaust (Toronto: Second Story Press, 1995), p. 105.

4.6 Faye Schulman. Practicing with a Rifle, 1943. Jewish Partisan Education Foundation.

4.6 Faye Schulman. Practicing with a Rifle, 1943. Jewish Partisan Education Foundation.

Caption: “This photo is really part of my history as a partisan. This is my ‘new’ automatic rifle…. I really had to practice how to shoot this one.” Faye Schulman, A Partisan’s Memoir: Woman of the Holocaust (Toronto: Second Story Press, 1995), p. 115.

4.7 Faye Schulman.

4.7 Faye Schulman. Schulman with her Detachment, 1942. Jewish Partisan Education Foundation.

Caption: “I am on the ground, the third from the right with my Red Cross box behind my head. Ivan Vasilewich, the Brigade’s doctor, is in the center, hands crossed in front. As you see, one girl and all boys. You can imagine that sometimes it was a little hard because there was nobody with me.” Faye Schulman, A Partisan’s Memoir: Woman of the Holocaust (Toronto: Second Story Press, 1995), p. 147.

4.8 Faye Schulman.

4.8 Francesco Boix Collection. Francesco Boix Mauthausen registration photographs, 1940. Arxiu Nacional de Catalunya. Departament de Cultura.

4.9 Paul Ricken/FrancesBoix Collectioin

4.9 Paul Ricken/Francesco Boix Collection. Naked Soviet POWs, 1944.

Caption: A group of naked Soviet POWs, who were sent back to the Mauthausen main camp from the satellite camp of Melk in the fall of 1944, stand in line during a roll call. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC, courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD.

4.10 Paul Ricken/Francesco Boix Collection.

4.10 Paul Ricken/Francesco Boix Collection. The frozen body of a Jewish prisoner who was beaten to death by the SS lies in the snow, 1943. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD.

4.11 Paul Ricken/Francesco Boix Collection.

4.11 Paul Ricken/Francesco Boix Collection. Prisoners (lower left) at forced labor in the Wiener Graben quarry at the Mauthausen concentration camp, 1942. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD.

4.12 Paul Ricken/Francesco Boix Collection.

4.12 Paul Ricken/Francesco Boix Collection. Commandant Franz Ziereis points out something to Heinrich Himmler and other SS officials while viewing the quarry during an inspection tour of the Mauthausen concentration camp, 1941. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC, courtesy of Archiv der KZ-Gedenkstaette Mauthausen

Caption: Commandant Franz Ziereis points out something to Heinrich Himmler and other SS officials while viewing the quarry during an inspection tour of the Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria. Pictured in front from left to right are: Heinrich Himmler, Franz Ziereis and Ernst Kaltenbrunner. To the right of Kaltenbrunner is Josef Kiermaier.

4.13 Salva Rubio (writer), Pedro J. Colmbo (artist), and Aintzane Landa (colorist). The Photographer of Mauthausen, 2020 (English edition). Dead Reckoning/Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD.

4.13 Salva Rubio (writer), Pedro J. Colmbo (artist), and Aintzane Landa (colorist). The Photographer of Mauthausen, 2020 (English edition). Dead Reckoning/Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD.

Caption: A well-researched graphic novelization of Francesco Boix’s Mauthausen ordeal featuring detailed drawings of many of his photographs. This graphic novel brings forward the issues of despair and survivor’s guilt, and the confounding question of how to narrate such sadistic systems to those who have not experienced them.

4.14 Unknown photographer.

4.14 Bone-crushing machine used by Sonderkommando 1005 to grind the bones of victims after their bodies were burned in the Janowska camp, 1944. US Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC.

Caption: The Soviet war crimes investigation team, “Extraordinary State Commission for ascertaining and investigating crimes perpetrated by the German–Fascist invaders and their accomplices,” made this photograph of three former members of the Sonderkommando 1005 unit (left to right are: unknown, David Manusevitz, and Moses Korn) next to a bone crushing machine in the Janowska concentration camp soon after liberation. Soviet prosecutor Colonel Lev Smirnov testified about the bone crushing before the Nuremberg Trials in February 1946, where he submitted photographs of the machines. Smirnov stated that the Germans exterminated hundreds of thousands of Soviet citizens, war-prisoners, and nationals of foreign states at Janowska. In addition to the bone crusher from Janowska, the Soviets also found a bar of soap made from human fat and gloves of human skin, which can be seen in the Museum of the Great Patriotic War in Kiev.

4.15 The Open Door; William Henry Fox Talbot

4.15 William Henry Fox Talbot. The Open Door, 1844. Salted paper print from a calotype negative. Plate VI of The Pencil of Nature (London, 1844–46). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, CA.

Caption: In his text to The Open Door, Talbot compared vernacular photographic realism, the forerunner of the everyday snapshot, to Dutch genre painting that realistically portrayed daily human activities with a sense of unidealized immediacy. This was exemplified by Flemish painter Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s (ca. 1525–1569) unsentimental, well-organized compositions of peasant life.

About the Sonderkommando Quartet Photographs

The black frame of the gas chamber’s doorway or window is visible in photographs 280 and 281. In photograph 281, a fragment of photograph 282 can be seen on the left, which means that the order in which the images were taken contradicts the numbering of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum: photograph 282 of the women undressing in the birch woods precede the images of the cremation pits.[i] The original negatives and prints have been lost. The reproductions are from prints made in the 1950s. The numbering was assigned by the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum. Photographic details are provided to help clarify what was taking place.

4.16 Alberto Errera

4.16 Alberto Errera/Auschwitz Sonderkommandos. No. 280, framed by the gas chamber’s doorway or window, 1944. Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, Oświęcim, Poland.

Caption: A fenced off area containing pits used for the burning of bodies when the crematoria could not keep up with the workload in 1944. Bodies were burned in outdoor fire pits when the crematoria were full.

4.17 Alberto Errera

4.17 Alberto Errera/Auschwitz Sonderkommandos. No. 280, framed by the gas chamber’s doorway or window (detail) 1944. Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, Oświęcim, Poland.

4.18 Alberto Errera

4.18 Alberto Errera/Auschwitz Sonderkommandos. No, 281, framed by the gas chamber’s doorway or window, 1944. Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, Oświęcim, Poland.

Caption: Alberto Errera was a Greek naval officer who was shot and killed after striking an SS officer.

4.19 Alberto Errera

4.19 Alberto Errera/Auschwitz Sonderkommandos. No. 282, Naked women being taken to the gas chamber, 1944. Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, Oświęcim, Poland.

4.20 Alberto Errera

4.20 Alberto Errera/Auschwitz Sonderkommandos. No. 282, Naked women being taken to the gas chamber (detail), 1944. Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, Oświęcim, Poland.

4.21 Alberto Errera

4.21 Alberto Errera/Auschwitz Sonderkommandos. No. 283: Trees near the gas chamber, taken shortly after No. 282, 1944. Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, Oświęcim, Poland.

Caption: The photographer, shooting from the hip, aimed the camera too high.

4.22 Emanuel Leutze

4.22 Emanuel Leutze. Washington Crossing Delaware River, 1851. 149 x 255 inches. Oil on canvas. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Caption: German-born American historical painter Emanuel Leutze’s glorified depiction of Washington’s attack on the Hessians (German troops hired by the British to fight the Americans) at Trenton New Jersey on December 25, 1776, was a tremendous success in America and in Germany. The soldiers in the boat represent a cross-section of the American colonies and symbolize the revolutionary cause, carrying and uniting the men towards a common goal of liberty. Leutze began his first version of this subject in 1849. It was damaged in his studio by fire in 1850 and, although restored and acquired by the Bremen Kunsthalle, was again destroyed in a bombing raid in 1942. Many studies for the painting exist, as do copies by other artists, making it one of the most iconic images in the history of American art.

4.23 The Golem

4.23 The Golem, How He Came into the World (film still), 1920. Directed by Paul Wegener/Carl Boese. Written by Paul Wegener/Henrik Galeen. German Film Museum (Deutsches Filminstitut), Frankfurt, Germany.

Caption: A Golem is an animated anthropomorphic being in Jewish folklore that is created entirely from inanimate matter, such as clay or mud. The classic narrative of the golem tells of how Rabbi Judah Loew of Prague (1525-1609) creates a golem to defend the Jewish community from antisemitic attacks. However, the golem grew violent, forcing Rabbi Loew to destroy it. Legend says that the golem remains in the attic of the synagogue (Altneushul) in Prague, ready to be reactivated if needed. The golem likely inspired tales such as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s poem, “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice” (1797), Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818), and films such as the one pictured here. See: Moshe Idel, Golem: Jewish Magical and Mystical Traditions on the Artificial Anthropoid, (Albany, New York: State University of New York Press, 1990).

4.24 Gustave Doré

4.24 Gustave Doré. The Legend of the Wandering Jew, A Series of Twelve Designs, with explanatory introduction, 1856. 21-11/16 x 15-1/4 inches. Wood engraving on paper.

Caption: The Wandering Jew is a mythological symbol from medieval Christianity that spread throughout Europe during the thirteenth century. According to legend, a Jew taunted Jesus on his path to his crucifixion and was cursed to walk the earth until the Second Coming. Of course, the alleged action of one was applied to all. This Doré engraving, with the crucified Christ in the background, in one of a series of twelve Doré engraving first published by Michel Levy Frères. Paris, 1856. This was popular collection and went through numerous editions. The original plate masters were drawn in pen and ink.

4.25 Rachel Posner.

4.25 Rachel Posner. Menorah With Nazi Flag, circa 1932. Shulamith Posner-Mansbach/United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC.

Caption: On the back of this photograph, Rachel Posner wrote in German:

Chanukah 5692 (1932)

“Death to Judah”

So the flag says

“Judah will live forever”

So the light answers

The date of 1932, inscribed on the back, likely is when the photograph was printed. Rachel Posner was married to Rabbi Dr. Akiva Posner, Doctor of Philosophy from Halle-Wittenberg University, who served as the last Rabbi of the community of Kiel, Germany before the Holocaust. After Rabbi Posner publicized a protest letter in the local press expressing indignation at the antisemitic posters that had appeared in the city: “Entrance to Jews Forbidden,” he was summoned by the chairman of the local branch of the Nazi party to participate in a public debate. The event took place under heavy police guard and was reported by the local press. When the violence in the city intensified, the Rabbi pleaded with his community to flee with his Rachel and their three children to Eretz Israel (The Land of Israel), then The Mandate for Palestine. [xxxi]Before their departure, Rabbi Posner convinced many of his congregants to leave for Israel or the United States. The Posner family left Germany in 1933 and arrived in Israel in 1934. Posner descendants continue to light Hanukkah candles using this menorah. More at: www.yadvashem.org/artifacts/museum/hanukkah-1932.html