Sándor Szilágyi, PhD, is a Hungarian media theorist, writer on photography, living in Budapest, Hungary. His interest range from Hungarian art photography, documentarist photography, and the theoretical questions of photography.

This is the sixth of ten essays on photography by Sándor Szilágyi.

Hyperfocus

Miklós Gulyás is by definition a street photographer: he only photographs in the city, loitering in Budapest, whatever catches his eye in public or open spaces. He doesn’t go after the life of the people he meets, being satisfied with what is written on their faces, in the posture of their body, in a gesture in the moment of their encounter.

This is very different from socio-photography. Gulyás does not agitate with his images, he doesn’t want to change anything – he doesn’t even lament over the fate of the people in them. However, from the contents of the preface to his album[1] it seems he could even be practising “committed” photography: if I understand correctly, he hates the Turul[2] settling on the city just as much as Donald Duck swooping into its place. But, it seems he has the make-up of a lyrical philosopher rather than an epic poet, and certainly not a propagandist or agitator.

As regards his prints, the most outstanding thing about them is that they are very black and white; this strikes the eye immediately when you compare them with those of the other distinguished Hungarian photographer working in the genre, Imre Benkő, who in contrast with Gulyás composes with subtle shades of grey. The two photographers see differently, even if they seemingly look at the same thing.

Gulyás’ images are dramas, while the greyness of Benkő’s conveys the tragic hopelessness and monotony of everyday life. This difference is also reflected in their shooting techniques: Benkő likes to photograph in soft diffuse light, while Gulyás prefers sharp sunlight and uses a filter which increases contrast to boot (in all probability, a relatively strong orange one). This produces the surreal sight of clouds looming out of the dark sky and figures sharply standing out from the “stage setting” of the dark street.

Another difference is that, although both use an ultra wide-angle 20-24 mm lens, Benkő avoids distortions of human figures, mainly their faces, and composing them to the edges or corners, while Gulyás uses this alienating effect more boldly.

While both construct their images based on geometric forms, they differ in that Benkő makes the sections suffocatingly narrow and sometimes cuts into forms almost hurting the eye and creating an oppressive atmosphere, and Gulyás edits the stage of his images broadly, as if he wanted to place them in abstract, cosmic space. This, too, is an oppressive world, but differently.

But the real difference lies in the relationship between the actors and the background. With Benkő people always play the main role; people who blend into their environment perfectly. The trouvaille of his images is that he, too, is one of those people whom he photographs, because he doesn’t gape at what he sees. So we do not take a sociographic trip to an exotic social clime but immediately we feel at home in the world of the works, and for this reason the characters are not “workers” but flesh and blood human beings like us.

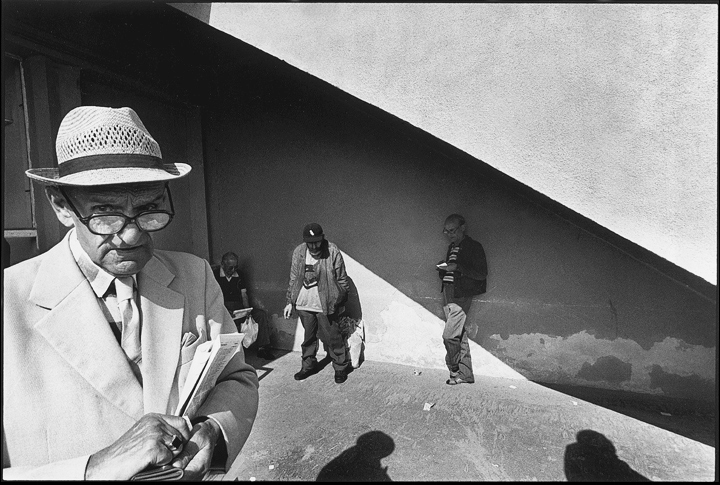

Gulyás sees things vice versa. For him the environment has a role of at least the same weight as the people in the image, and they both look strange on the otherwise familiar cityscapes. It’s as if not people but statues of people were erected in a surreal, seen and shown space. The figures haven’t come from anywhere and are not going anywhere; they just stand and stand and stand there – as I’ve said, like statues (often there is also some sort of plinth beneath them). These are dream-like, timeless visions similar to de Chirico’s paintings about the cities where we live. The houses, streets and squares are merely scenes and the characters are often only staffage in the historical drama.

The technical means of bringing the actors and the backgrounds to the same visual level (besides wide-angle lenses, which subjectively have a great depth of field) is hyperfocus: Gulyás usually does not focus on the actors, but somewhere between the figures and the background, and as a consequence the background is not blurred but has the same sharpness as the figures. And so the hierarchy instilled in us is broken down: background and actors become image forming elements of equal status.

Sometimes Gulyás even goes a step further: he doesn’t only neutralise the customary structural principle, but inverts it, giving the image a new hierarchy: not the background but the figures in the foreground are out of focus, as if they were merely framing the rest of the image.

Subject matter

Gulyás does not divide the material in his album into chapters; only an empty page separates one subject or location from another. There would not be a lot of point in cutting up an album with a fairly uniform image world and atmosphere – although one theme, the Széchenyi baths series made between 1995–97, does stand out from the rest.

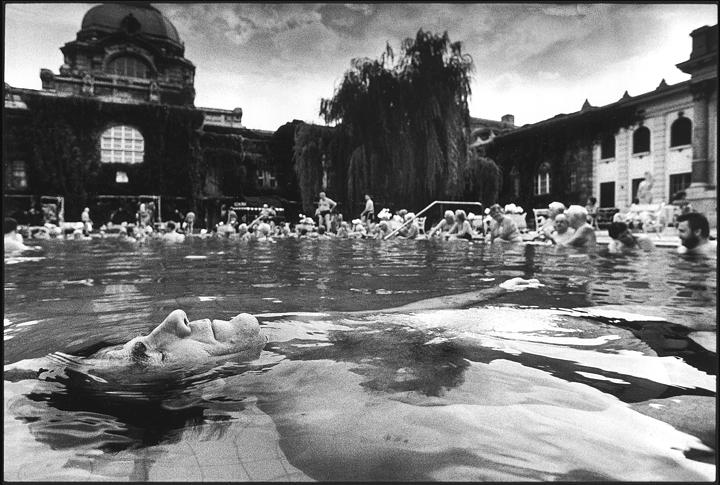

It is rare to see such powerful material. In fact, I could repeat everything I’ve said so far about this series, except, of course, the bits about bright sunlight, as here (at least in half the prints) a steamy, misty, mysterious ambience dominates the image. But even in these the dramatic contrast of black and white form the crux.

The other crucial factor is Gulyás’ humour – a little more pointed, less refined than Benkő’s. For example, a female nude carved in stone looks in the same direction as a Gulyás-carved statue of a woman, as if they were twins. The figure of a man, whose not inconsiderable belly stares at the sky, is the embodiment of male self-assurance. The figure floating on his back with eyes closed is reminiscent of a fresh corpse in the water.

The material from a few years before (1991) taken at the Keleti railway station in Budapest is also very powerful. Perhaps here the supreme way in which Gulyás is able to see and make us see customary, everyday scenes is best demonstrated. I think the main difference is that his later images seem to be more complex, with more actors and richer backgrounds, while his earlier works are dominated by a more portrait-like approach. His more recent images are more abstract and philosophic, more like visions.

The shots of the trotting races are good, and the figures evoking a bygone bourgeois world are a nice counterpoint to the following block taken at right-wing political demonstrations of recent years, images full of figures with heads not distorted by Gulyás’ lens but thus endowed by mother nature.

I consider the series shot in the Kerepesi cemetery less successful. It seems that it is easier for Gulyás to carve statues from living figures than the other way round, to breathe life into stone carvings. The series about the tram (and, of course, the tram stops and large Budapest squares) is good if somewhat uneven; I believe those works where I feel no one else could have made them in this way are particularly successful.

The study comprising otherwise excellent shots of the opera house ball stand out from the others, perhaps partly because they were taken with a flash, exploiting the lack of sharpness due to movement and thus inevitably exuding a different atmosphere from the icon-like motionless scenes in daylight. But perhaps these images are also different because the wealthy are their subject and not everyday people you meet walking down the street or on the tram.

Although this is somewhat of an aside, as Gulyás’ works are visionary and not socio-photography, it is interesting the extent to which presenting the life of the well-to-do has missed the attention of Hungarian photographers – and I’m not thinking of the gutter press. Similarly, they have neglected one of the most striking changes in the urban landscape in Budapest (and provincial cities): the world of Chinatown. Besides McDonald’s, the appearance of Chinese restaurants and snack bars, the Chinese market and the Asian population has produced one of the most distinctive changes to the city scene in Hungary since the change of political system. I should be very interested to see what Gulyás (or a photographer of comparable stature) would produce from that.

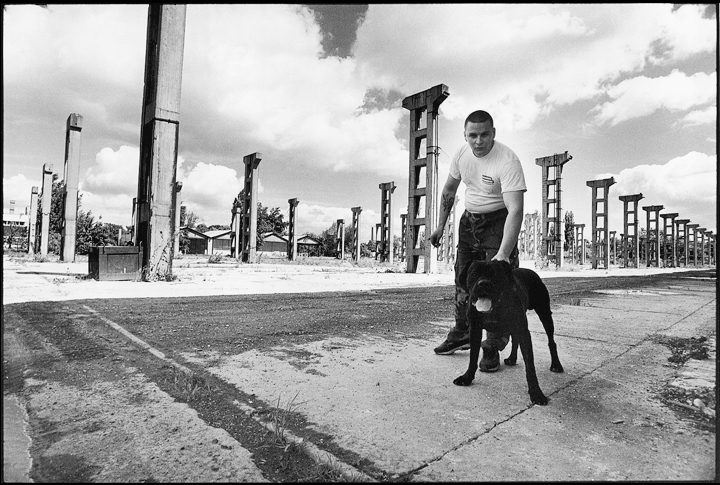

The other change is the emergence of violence. Gulyás perceives this process very subtlety: although it is not directly the subject of his images, the feeling of threat and defencelessness resonates in almost all of them. From this aspect is incredibly forceful, stripped to its bare essence: a security guy can barely restrain his snarling dog poised to leap at us. It would be a fitting final image for his album.

(Beszélő, February 2002)

© Sándor Szilágyi

[1] 1 másodperc – budapesti fényképek. [One Second – Photographs of Budapest] Új Mandátum Könyvkiadó, 2001. The album’s entire picture material can be viewed at www.fotografus.hu.

[2] The Turul is an eagle-like bird from Hungarian mythology, which was adopted by the Hungarian nationalist movement as its emblem.